The Da Vinci Notebooks

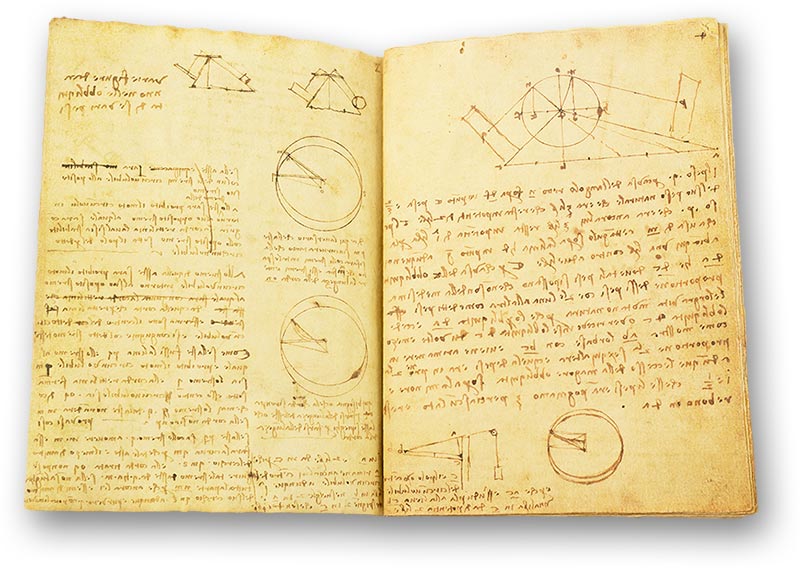

Leonardo da Vinci's sketchbooks and notebooks encompass thousands of pages that provide a fascinating insight into the spirit of the universal genius. Throughout his life, Leonardo recorded his ideas, notes, and sketches in books and sometimes on loose sheets, which were only bound after his death. Today these manuscripts are among the most coveted codices in the world. In 1994, Bill Gates paid $30.8 million for the Codex Hammer at an auction, making it the most expensive manuscript ever sold.

The studies of his great masterpieces stand out among the breathtaking variety of entries, which made it possible to understand the artistic creation process and thus pave the way for the growth of the following generation of artists. There is hardly a topic in art or science to which da Vinci did not devote his creative genius on these pages. The records are evidence of his skills as an artist, naturalist, anatomist, engineer, astronomer, and more. They contain practical inventions from a wide range of areas, including constructions for using hydropower or imaginative flying machines. Mundane thoughts such as shopping lists or travel descriptions are also mixed between exuberant flights of thought, enriched with everyday observations, witticisms, and even jokes. Today, Leonardo's notebooks are kept in the most prestigious museums and private collections in the world.

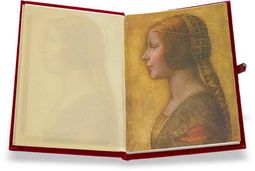

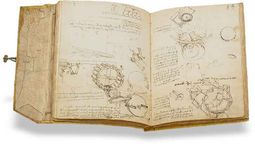

Demonstration of a Sample Page

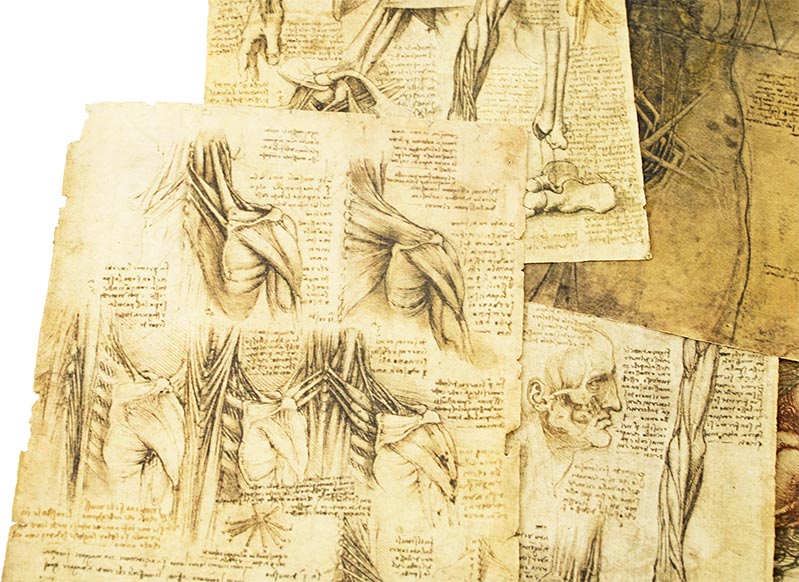

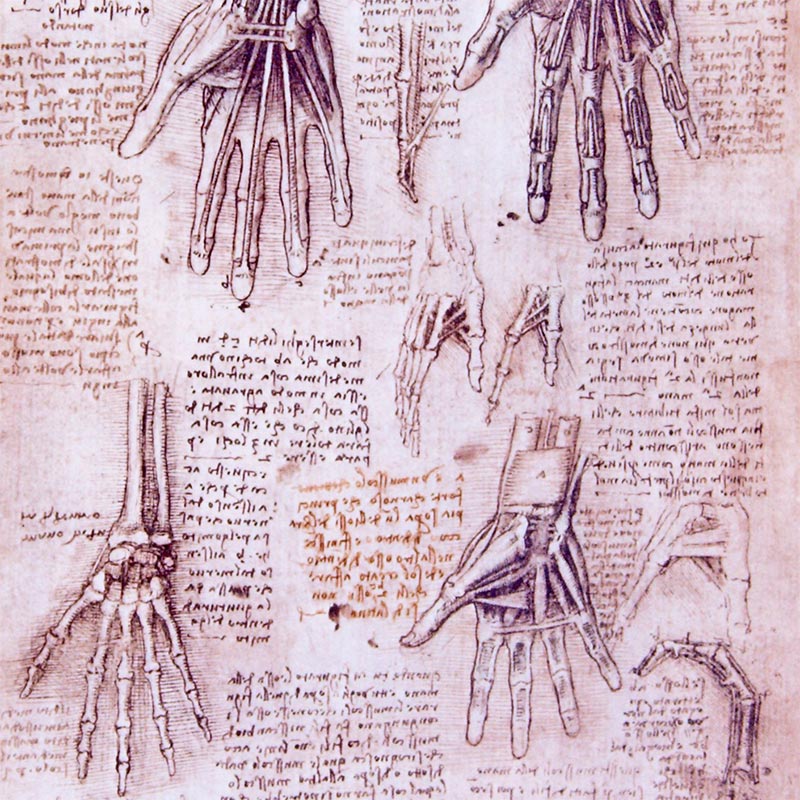

Corpus of the Anatomical Studies

Vascular System According to Galen

Complete with Leonardo da Vinci’s signature mirror writing, this sketch is one of countless studies of the human body by the world’s most famous polymath. The figure is a muscular middle aged man with a bald head and deep, penetrating eyes to remind us of his humanity as we dissect him. It is a remarkably striking and powerful portrait for such a simple sketch.

Galen was a Greek physician in the Roman Empire during the 2nd century and the greatest medical expert in antiquity. His teachings remained the backbone of a doctor’s curriculum throughout the Middle Ages. However, Greco-Roman cultural taboos against dissection meant he was ignorant of many aspects of human anatomy, hence the beautiful but flawed vascular system created here by Leonardo.

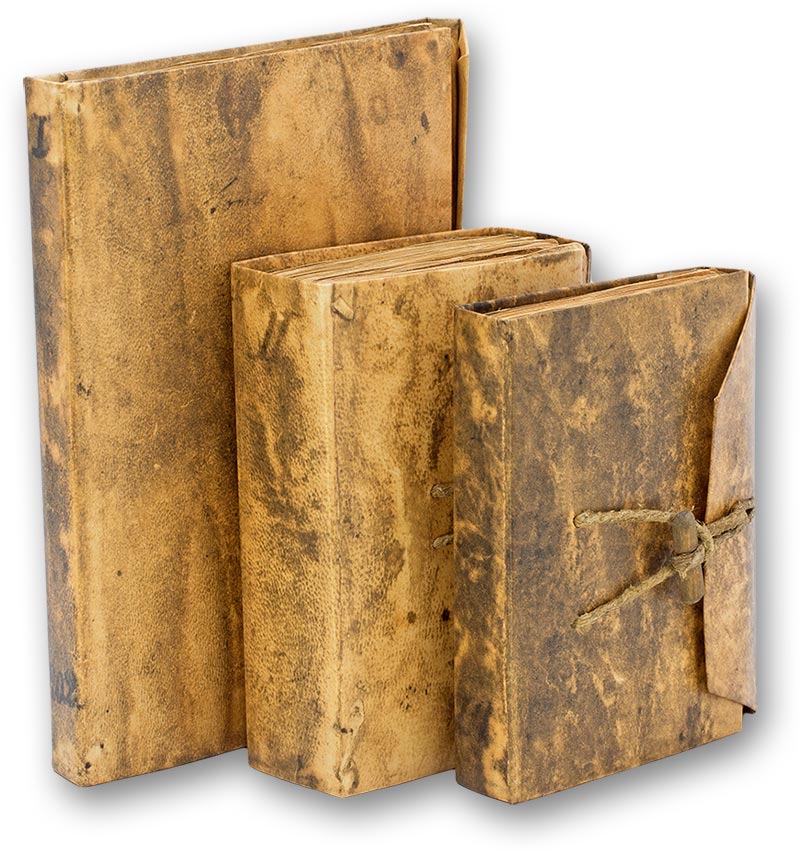

The Personal Notes of a Polymath

To the facsimile

The genius of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) has been preserved in the great number of his journals and sketchbooks that have survived to the present. In total, the da Vinci notebooks consist of 13,000 pages of notes and drawings covering the full spectrum of art and science. They are also filled with Leonardo’s observations of everyday life and while travelling throughout Renaissance Europe.

To the facsimile

Some were composed in small pocket notebooks that could be tied shut and carried on one’s person, but most are compendia of loose papers bound together posthumously by Francesco Melzi (1491-1570), who was both apprentice and heir to the great polymath. Just as Melzi looked after the aging Leonardo in life, he saw to Leonardo’s legacy in death by preserving and collating his mountain of notes and sketches.

Today, these manuscripts are featured in some of the finest public and private collections around the world. The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci not only offer tremendous insight into the life of the most famous Renaissance Man in history, but represent artifacts of tremendous worth for the history of art, engineering, mathematics, anatomy (both human and animal), and various other fields of research.

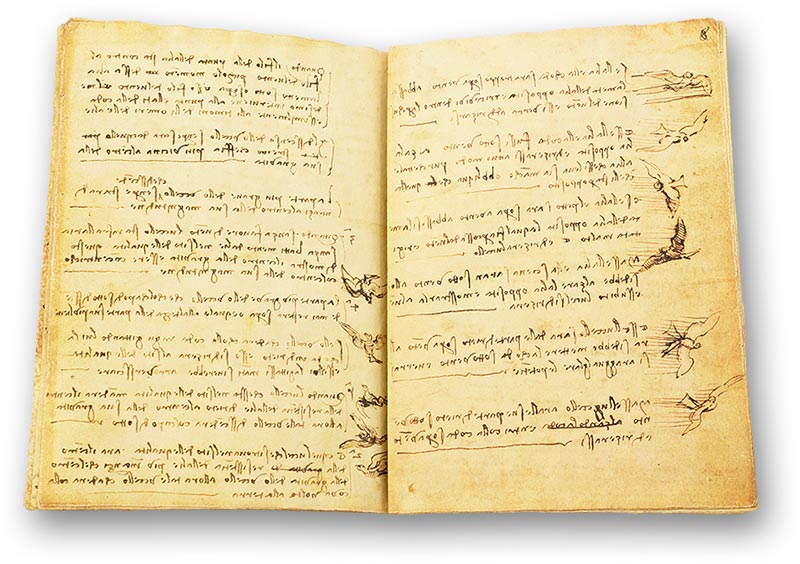

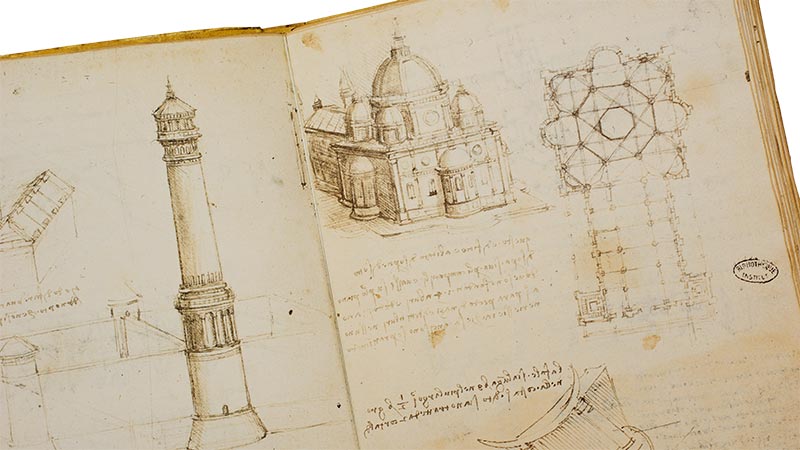

Enigmatic Texts Intended for Publication

To the facsimile

One of the more curious facts concerning the da Vinci notebooks is the fact that they were written in so-called “mirror writing”, which is created by forming the letters in reverse so that they appear normal when reflected in a mirror. Whether serving as a primitive form of cipher or making the word AMBULANCE appear normally in a rear-view mirror, it has been used continuously for centuries. However, Leonardo made it clear that he intended for his personal journals to be published collectively someday – why it was not remains unknown.

To the facsimile

Actually, the explanation for this is rather simple: the great polymath was left-handed and used mirror writing as a matter of convenience because it was easier on his hand to write from right to left. Furthermore, the text is filled with shorthand and symbols that served to reduce the distance between Leonardo’s genius and the page before him. The da Vinci notebooks are filled with such interesting idiosyncrasies that serve to increase our fascination with the inner workings of the greatest minds of the Renaissance.

The National Collections

To the facsimile

Over the past few centuries, the most prestigious libraries in the world have sought out the da Vinci notebooks both for the opportunities they provide to researchers as well as the prestige they bring to the institutions that hold them. Naturally, Italy is the world’s leader with first-class collections found in Turin, Florence, Venice, and Milan covering the breadth and width of Leonardo’s career. Aside from the British Library, both the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Library at Windsor Castle possess fine collections that are a close second. They mostly originate from private acquisitions that were subsequently donated to the state and include particularly extensive studies of human anatomy.

To the facsimile

The extensive 12-volume collection of the Institut de France comprises nearly 2,000 pages that were brought back to Paris by Napoleon as war booty from his Italian campaign of 1796/97. The extensive collection covers both practical and theoretical themes ranging from mathematics and the various technical aspects of painting to designs for a pseudo-helicopter. Other noteworthy collections can be found in Madrid’s Biblioteca Nacional de España, focused in particular on architecture and engineering, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Despite being an Italian, Leonardo’s creative genius obviously has widespread appeal that inspires the curiosity of people the world over.

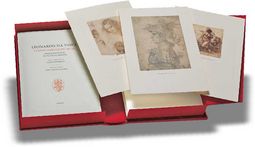

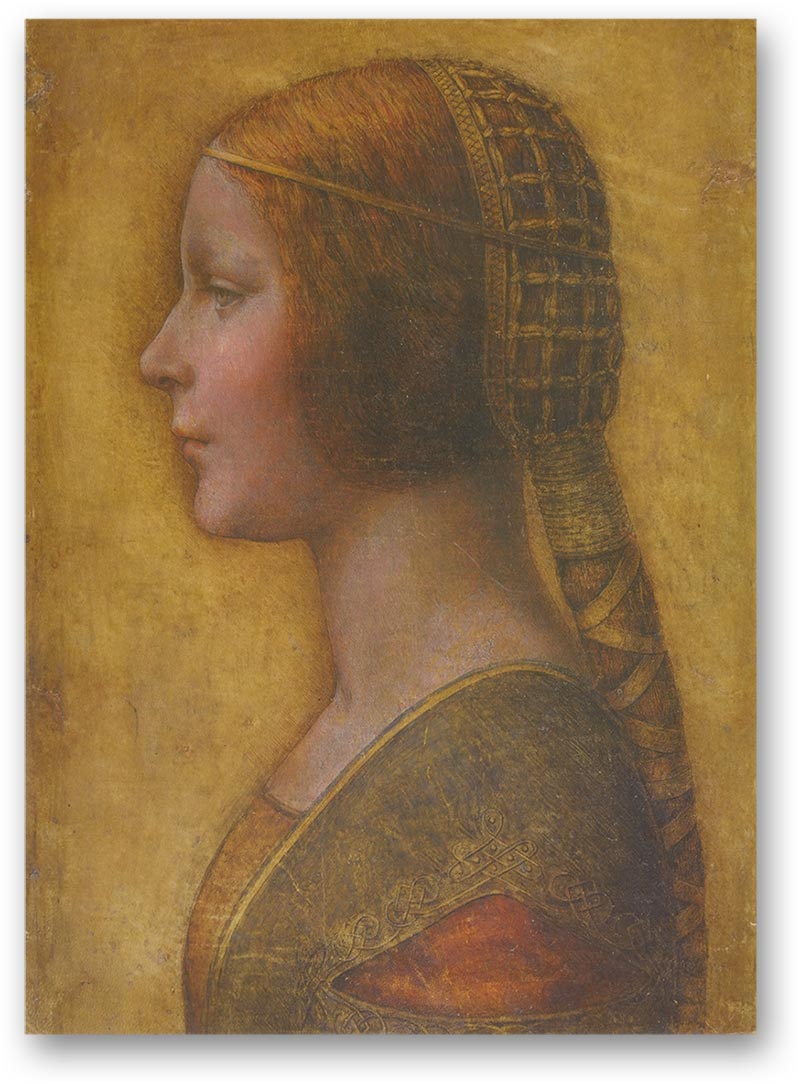

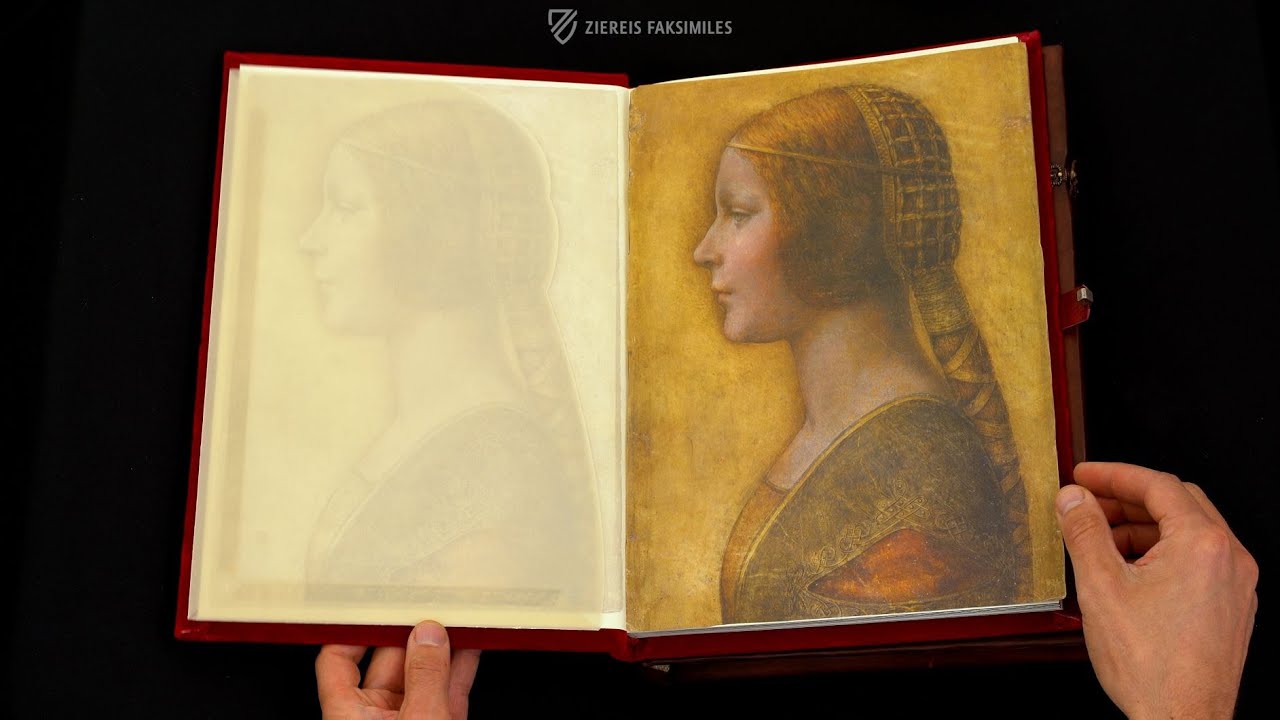

Studies of Famous Paintings

Leonardo da Vinci created some of the most iconic paintings of the Renaissance, including some of the most valuable pieces of art ever sold at auction. These masterpieces began as mere sketches. They were not created in a single session, nor on a single canvas, but are the result of countless attempts deemed insufficient, which were either scrapped off and painted over or thrown out entirely so that Leonardo could start afresh. The da Vinci notebooks represent a unique inside view of this process from one of the greatest geniuses of all time because they are full of the raw sketches and more advanced studies that later evolved into some of the most iconic works of Western Art.

To the facsimile

One can bear witness to the development of famous works like The Last Supper, The Battle of Anghiari, Virgin of the Rocks, The Adoration of the Magi, and The Virgin and Child with St. Anne in their studies, which are found among the manifold topics covered in the da Vinci notebooks. Despite being only sketches, these studies reveal the underlying structures that made Leonardo’s paintings the masterpieces that they are.

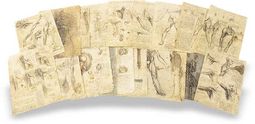

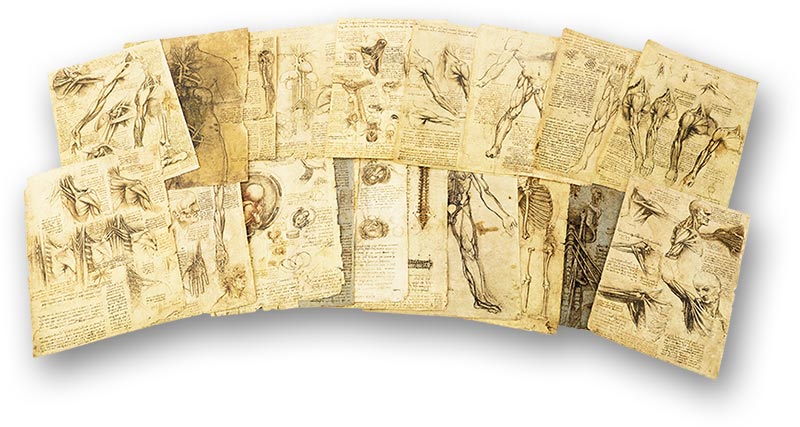

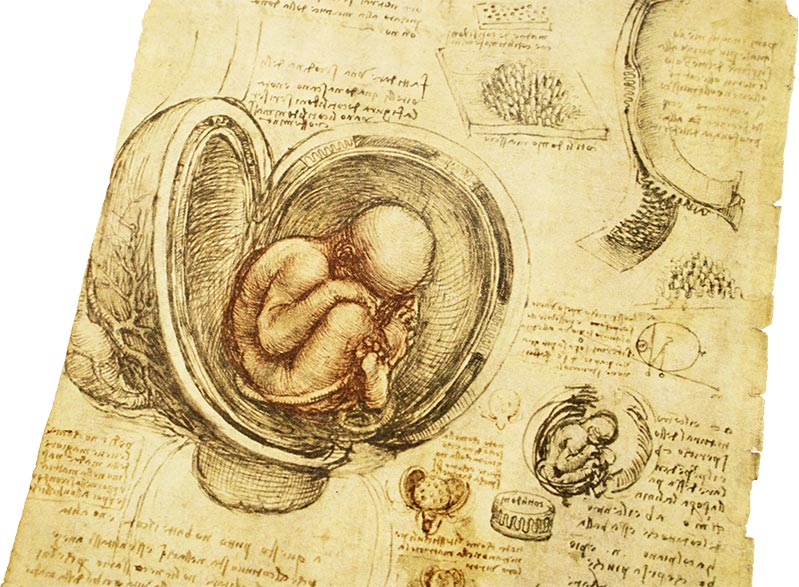

The Intersection of Art and Anatomy

To the facsimile

Generations of artists were influenced by Leonardo da Vinci, largely thanks to his widely-circulated notebooks and artistic treatises. Leonardo himself believed that painting was the highest of all arts and his Libro di pittura or Treatise on Painting was assembled at his request by his apprentice Francesco Melzi. It represents a comprehensive volume covering almost every technical aspect of painting and various theories of artistic composition. First published in 1651, it has since been tremendously influential for Western artists and is considered today to be the most important theoretical work in art history. The natural depiction of the human body was considered to be one of the highest achievements of an artist and as such was worthy of extensive study by Leonardo.

To the facsimile

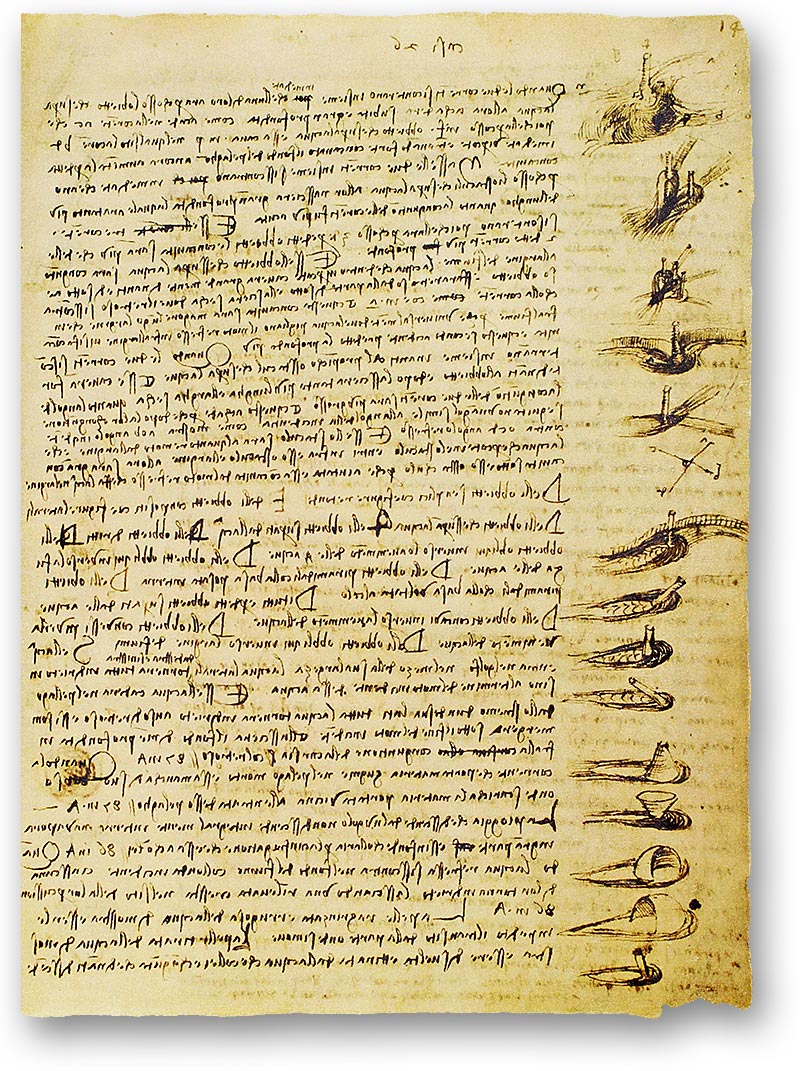

A compendium of 400 such drawings from the Royal Library at Windsor Castle has been assembled into the appropriately-named Corpus of the Anatomical Studies. Artistic and accurate in equal measure, they range from full-body depictions of the human form to detailed examinations of the blood vessels, organs, tendons, etc. Hands and feet in particular are closely examined. These diagrams are practically applied later in the manuscript to studies of famous paintings like the Virgin of the Rocks and The Last Supper. Generations of artists were influenced by Leonardo’s studious examination of the various techniques that he utilized.

Leonardo the Naturalist

Aside from the human form, the accurate depiction of animals and nature in general was of tremendous importance for someone trying to create truly complete artistic works. In Leonardo’s eyes, nature was a fascinating, never-ending cosmos filled with sources of inspiration, which is documented in two splendid collections from the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Leonardo’s finest studies of the appearance and mannerisms of numerous animals can be found in the Cavalli e altri animali or Horses and Other Animals, which includes numerous studies for famous works like the The Battle of Anghiari.

All of these artfully, even heroically depicted animals needed a worthy backdrop. The art of creating such a setting is illustrated in the Paesaggi, piante e studi d’acqua or Landscapes, Plants and Water Studies. It is a demonstration of Leonardo’s skills as a gifted draftsman as well as his observant eye as a proto-naturalist. It includes plant studies for works such as Leda and the Swan and studies of various bodies of water in order to naturally depict ripples and other natural phenomena.

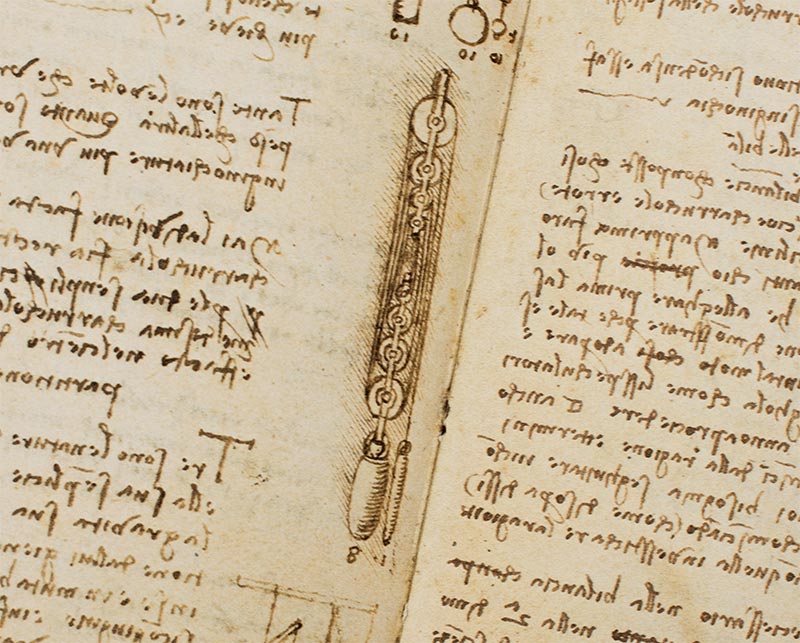

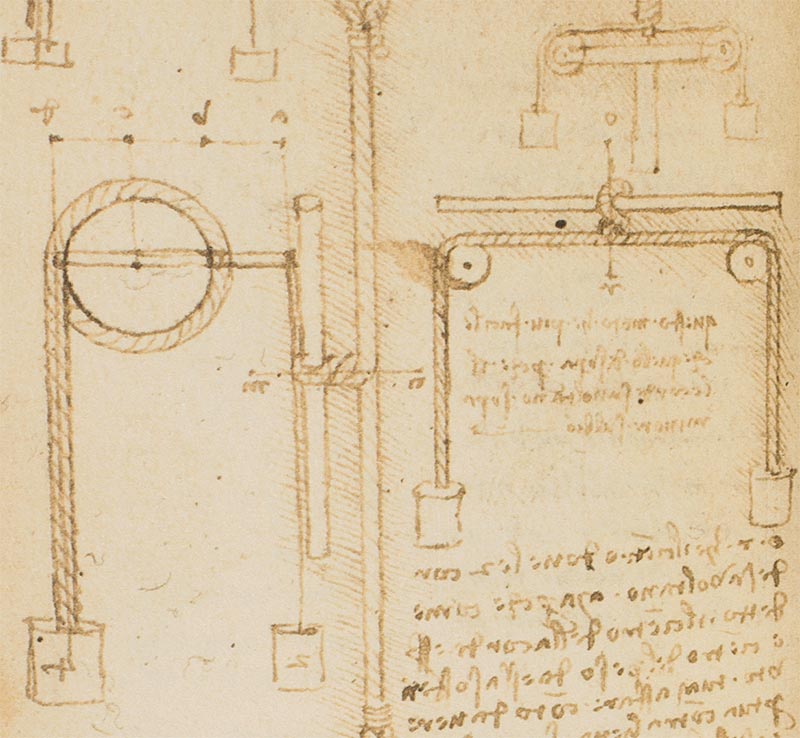

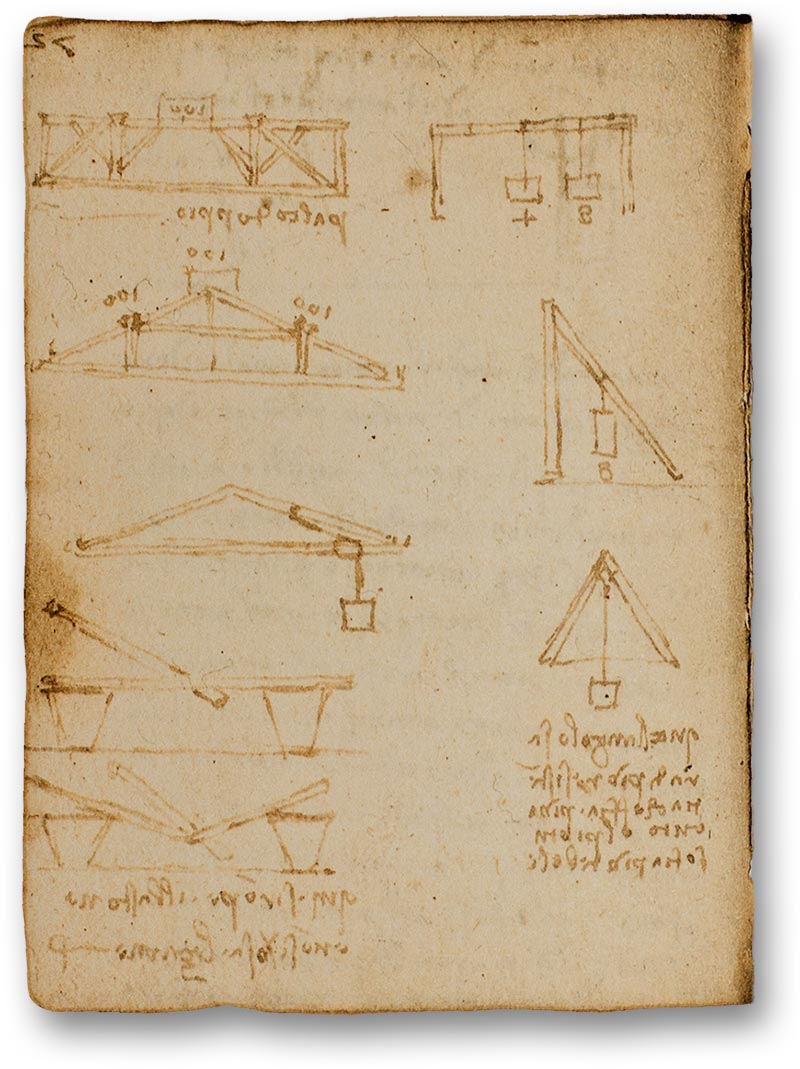

A Prophet of the Mechanical Age

Da Vinci lived in a labor-intensive world and imagined how man’s toil might be lessened through the help of machines. Advances in farming technology, such as the steel plow, and more advanced methods of crop rotation had already increased farm productivity throughout the Middle Ages and created a surplus workforce that fueled the rise of cities and the commercial economy of Early Modern Europe. Leonardo considered these developments and looked toward the future.

To the facsimile

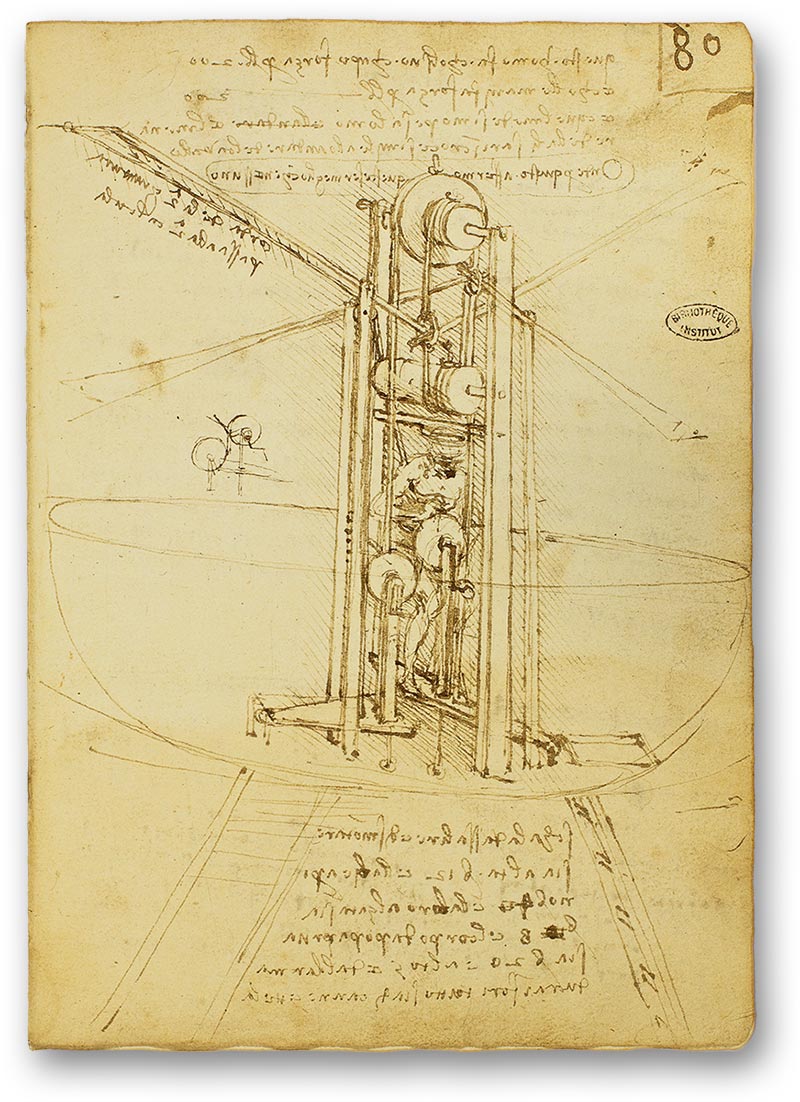

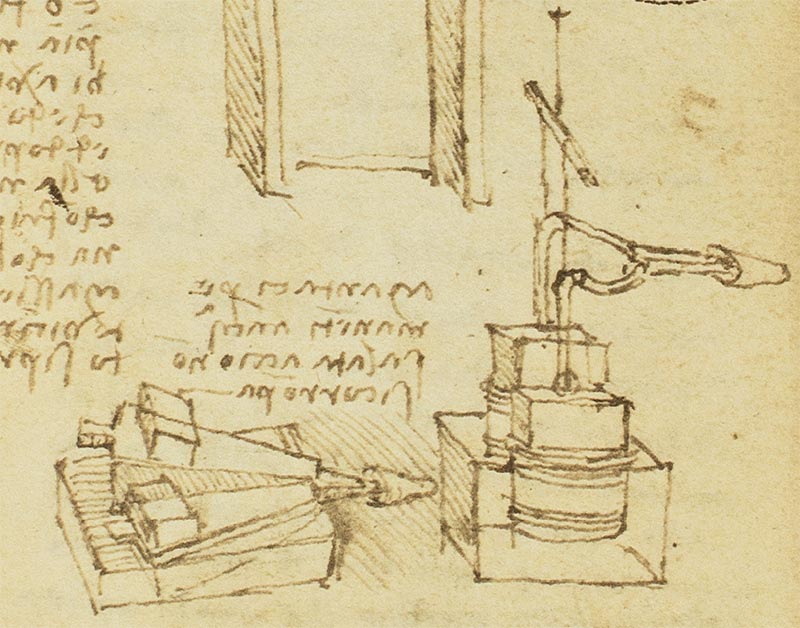

One of the greatest sources of his mechanical studies is the Codex Arundel, which is filled with theories of geometry and many practical designs for machines, including a submarine. As such, he might be considered a prophet of our modern mechanical age. What is more, Leonardo was an engineer who dreamed of flight.

To the facsimile

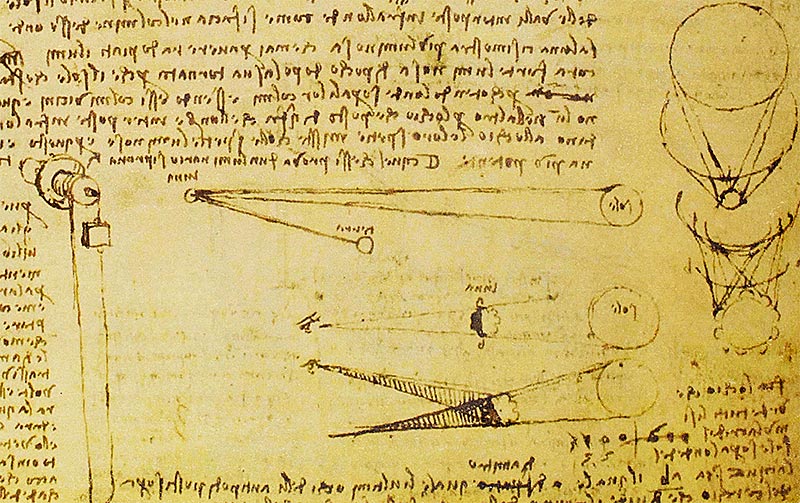

Unlike most of the da Vinci notebooks, which are compendia assembled after his death or journals containing his spontaneous ideas, the Codex on the Flight of Birds is focused on a single subject. He started by examining those naturally capable of flight and as a result, created some of the earliest studies of their anatomy and movements. Leonardo then famously designed flying machines, some of which he (unsuccessfully) tested on a hill near Florence. His ideas were centuries ahead of his time, and some of his designs might have worked if only a sufficient source of power had been available.

A Self-Improving Genius

To the facsimile

It is almost unfathomable that someone possessing the manifold genius of Leonardo da Vinci would feel inadequate in any way, but one of the most common characteristics of the highly successful is an unshakable sense of inadequacy. The Codex Trivulzianus is a testimony to the desire of Leonardo da Vinci to improve his own linguistic skills in Italian. Apparently, Leonardo’s literary education was the only aspect of his edification that was lacking. As such, various lists of vocabulary words can be found in the text.

To the facsimile

Additionally, one finds inter alia architectural plans of both a religious and military nature, war machines, and an accurate depiction of how an eclipse works. The Codex Trivulzianus is found today in the library of Sforza Castle, one of the largest citadels in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries that continues to be an architectural monument to this day.

The Forster Codices

To the facsimile

Rather than consisting of loose pages that were assembled later, either by Leonardo himself or his apprentice and heir Francesco Melzi, the so-called Forster Codices consist of five pocket notebooks originating from the years 1493-1505 that have been since condensed into three codices. As such, they offer a chronology of Leonardo’s thoughts as they occurred to him during the three respective epochs therein.

To the facsimile

They collectively represent a travelogue full of jokes and quips in addition to a few studies of horses and various equestrian statues in particular. The modern name for this collection comes from the Englishman John Forster, who bequeathed the extraordinary manuscripts to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1876.

Codex Atlanticus

To the facsimile

Comprising twelve volumes and over 1,100 leaves, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan possesses one of the largest collections of da Vinci’s sketches and notes, which were compiled in the late-16th century. Seized by Napoleon after his conquest of Milan in 1796, the Codex Atlanticus was returned after the war, unlike other looted da Vinci manuscripts that remained in Paris. This collection is called the Codex Atlanticus because its large sheets of paper were originally intended to be used for atlases.

To the facsimile

Unsurprisingly, the collection covers a wide variety of subjects ranging from mathematics to botany and included numerous interesting designs for mechanical inventions. Among them we find designs for fortifications and weapons, such as parachutes or a giant crossbow, as well as water wheels, Archimedean screws, and a hoist using a massive weighted wheel. Perhaps most exciting of all, some of Leonardo’s designs for flying machines can be found among this collection.

In the Private Collection of Bill Gates

To the facsimile

A particularly fine da Vinci notebook once resided in Holkham Hall, the home of the Earls of Leicester. The so-called Codex Leicester was purchased in 1717 by Thomas Coke (1697-1759), the 1st Earl of Leicester and a prominent patron of the arts in Georgian England. His greatest commission was the construction of Holkham Hall, which was completed five years after his death and is considered to be one of the purest examples of the Palladian Style. It was briefly referred to as the Codex Hammer after it was acquired in 1980 by the American oil tycoon Armand Hammer, but has been in the private collection of Bill Gates since 1994, when he purchased it at auction for $30,802,500 USD.

To the facsimile

Topics examined by Leonardo in these pages include cosmology, geometry, and meteorology but it is focused in particular on the element of water and its movements. This study is practically applied to erosion in rivers and the construction of bridges and is appended with various drawings and diagrams. Additionally, the Codex Leicester addresses the luminosity of the moon and explored the phenomenon of planetshine a century before it was proven by Johannes Kepler. It is no wonder that a titan of the computer age would be enticed to acquire such an artifact from the history of science, one of the most expensive privately-owned books in the world.