Late-Antique Illumination

Manuscripts created in distant antiquity are among the most coveted of historical artifacts due to their rarity and incredible value as historical sources as well as precious works of art and scholarship. These extremely rare specimens range from 4,000-year-old Egyptian papyri to ancient Hebrew texts to Greek works originating from the Hellenistic period to Roman manuscripts from Late Antiquity.

This artistic tradition was continued during the Middle Ages in the Eastern Roman- / Byzantine Empire with varying degrees of faithfulness to the classical artistic aesthetic. As with other periods, topics addressed in these manuscripts range from the biblical to the medical and the miniatures adorning these texts offer insights not only into ancient artistic techniques but their details also represent glimpses into daily life in the time and place that they were created.

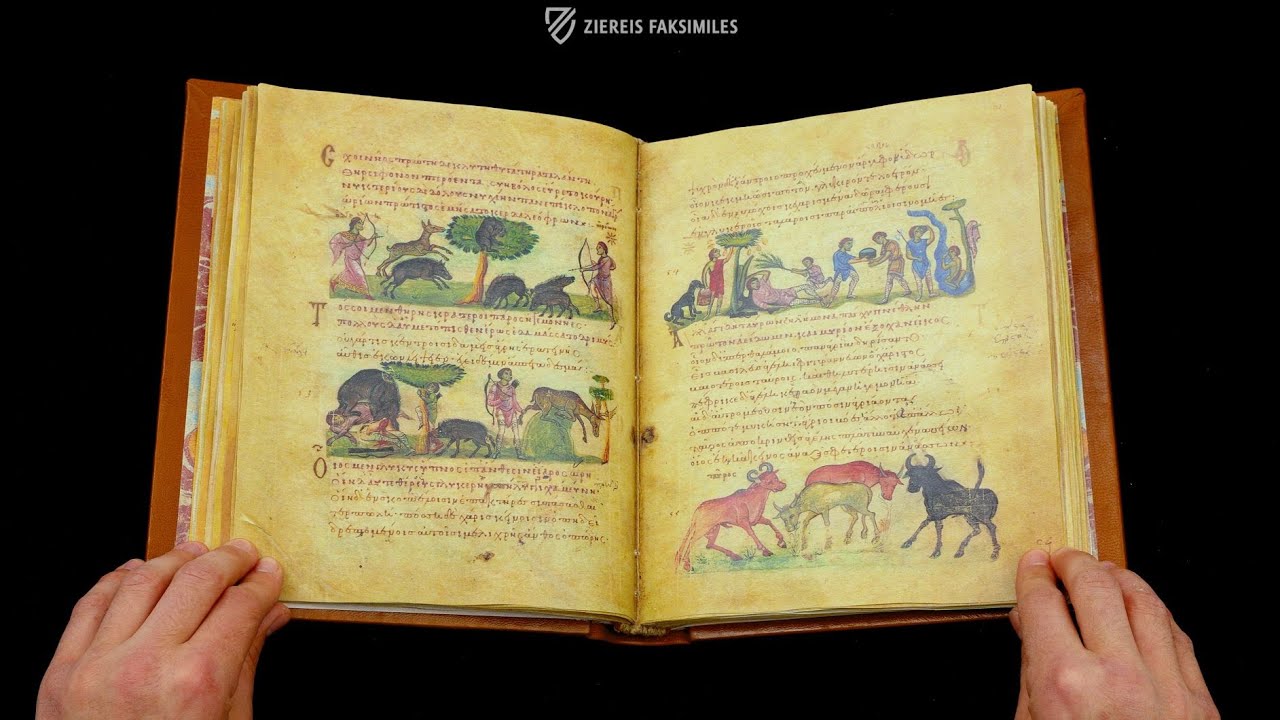

Demonstration of a Sample Page

Vergilius Romanus

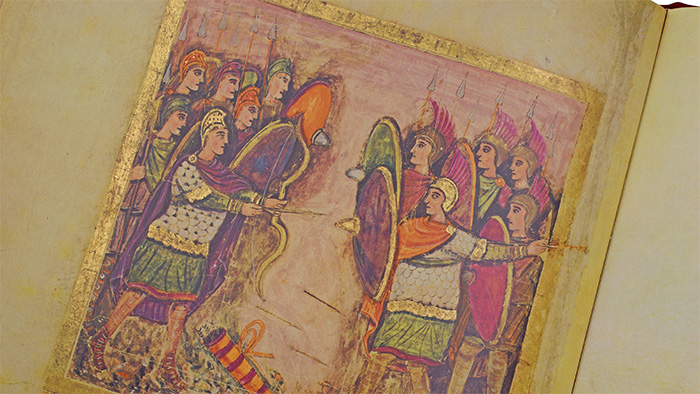

Eclogues: Tityrus and Meliboeus

The first of Virgil’s three principle works consists of a series of short pastoral poems written during turbulent period between 44 and 38 BC beginning with the assassination of Julius Caesar. Although aged by fifteen centuries, it is a testimony to the artistic refinement of Late Antiquity with remarkably naturalistic human and animal forms.

Eclogue 1 consists of a dialogue between two shepherds: as Tityrus sits under a tree playing his flute, Meliboeus relates how he has been forced off his land and has nowhere to graze his herds. It was commonly believed in antiquity that this was an allegory for the loss of his own family’s farm when the soldiers of Antony and Octavian were resettled after the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC.

Millennia-Old Wisdom

Precious few manuscripts have survived from the ancient world and most of those that have originate from Late Antiquity. Nonetheless, some ancient manuscripts in existence today, such as Egyptian papyri are more than 4,000 years old. Ancient Roman manuscripts are characterized by an aesthetic of idealized realism that was heavily influenced by Greek Hellenism but began to become more iconic and stylized in Late Antiquity.

Christianization of the Roman Empire resulted in the decline of sculptures, a primary art form in Classical Antiquity, in favor of more spiritually-oriented art like mosaics, architecture, reliefs, carved ivory diptychs and most importantly for us – manuscripts. Lost access to papyrus from Egypt caused Western Romans to turn to manuscripts made from parchment. Although this increased costs, it also increased the durability of manuscripts, which is a boon for modern researchers.

However, lost contact with the East had much more significant and damaging ramifications for learning in the West because Greek had long been the scholarly language of the Roman Empire and this separation resulted in intellectual stagnation. Nonetheless, art and learning did not disappear in this time and the term “Dark Age” is now largely rejected among scholars thanks to evidence of the resilient and surprisingly sophisticated artistic and intellectual culture that was now concentrated in monasteries, the most important institutions of the Early Middle Ages.

Late Antiquity or Early Middle Ages?

The periodization of the Middle Ages is one of the most hotly-contested subjects among historians, who cannot agree upon either a beginning or end date for the epoch. One of the main reasons for this is that it depends greatly upon the region, e.g. the period of cultural and artistic proliferation known as the Renaissance that began in the Late Middle Ages and ended in the Early Modern Period did not occur across all of Europe at the same time and took on a different character depending upon where it occurred, and also where it did not occur.

To the facsimile

Similar debates exist about the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Traditionally, Late Antiquity is defined as beginning during the Crisis of the 3rd Century (235-284), during which time the Roman Empire was afflicted by civil war, plague, famine, and economic depression. After nearly collapsing during this period, the Empire was saved by the ascension Emperor Diocletian (244-311) in the year 284 and the subsequent reforms he made.

Although the end of Late Antiquity in the West is traditionally dated to the final fall of Rome in 476, modern historians point out that although sovereignty passed from the Roman Caesars to Germanic kings, Roman institutions and people did not disappear overnight and the Germanic peoples who migrated to the Empire saw themselves as perpetuating its traditions. Thus, some historians date the end of Late Antiquity to the 6th century while others point to the crowning of the Emperor Charlemagne (742-814) in the year 800. Nonetheless, Roman culture continued to be influential throughout the Middle Ages.

Egyptian Papyri

Papyrus was the preferred ancient writing surface, which first appeared sometime around 4,000 BC and continued to be used for papal bulls into the 11th century. Although cheaply manufactured from the plant that grew abundantly in the Nile Delta, papyrus scrolls were relatively delicate, and could degrade from too much humidity. As a result, artifacts of papyrus manuscripts are among the rarest and most precious, offering priceless insights into Ancient Egypt in particular.

To the facsimile

The Papyrus Ani represents a rare, complete scroll that is dated to 1240 BC. It is a copy of the Egyptian Book of the Dead containing various magical formulas and religious instructions meant to guide the newly deceased into the afterlife and to achieve immortality or even deification. Its patron, Ani, is referred to several times throughout the text and is believed to have been a high-ranking official of the temple administration in Thebes, where the manuscript was discovered.

To the facsimile

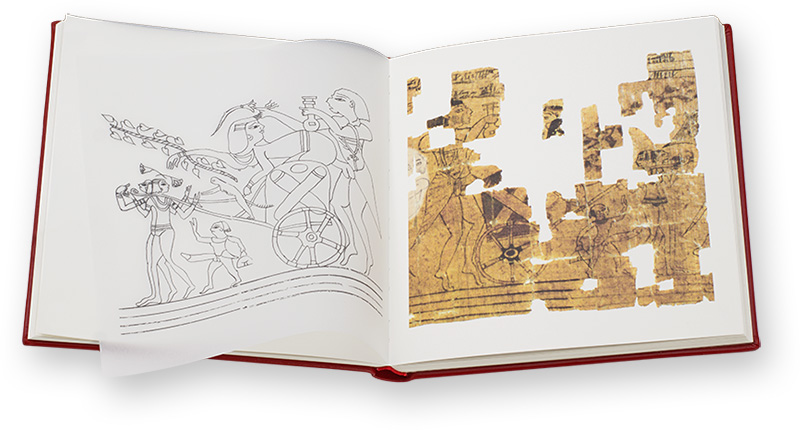

Other Egyptian papyri were focused on more worldly topics, like the so-called Erotic Papyrus, an explicitly sexual fragment from more than 3,000 years ago. Sometimes referred to as an Egyptian Karma Sutra, it is a mixture of erotica and satirical depictions of animals engaged in human activities, e.g. playing instruments or dressed as soldiers.

To the facsimile

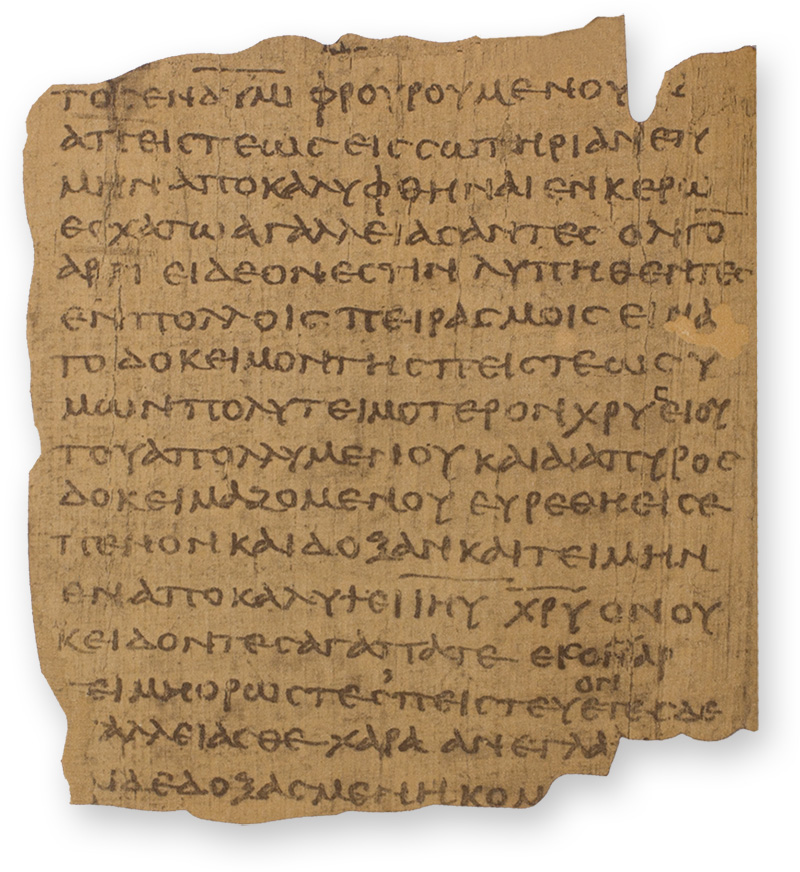

The oldest surviving specimen of the Epistles of St. Peter inter alia is known as the Bodmer VIII Papyrus. Acquired in 1956 by Swiss citizen Martin Bodmer, the nearly 1,800-year-old bundle of papyri represent some of the most significant textual witnesses to the Bible.

Ancient Hebrew Manuscripts

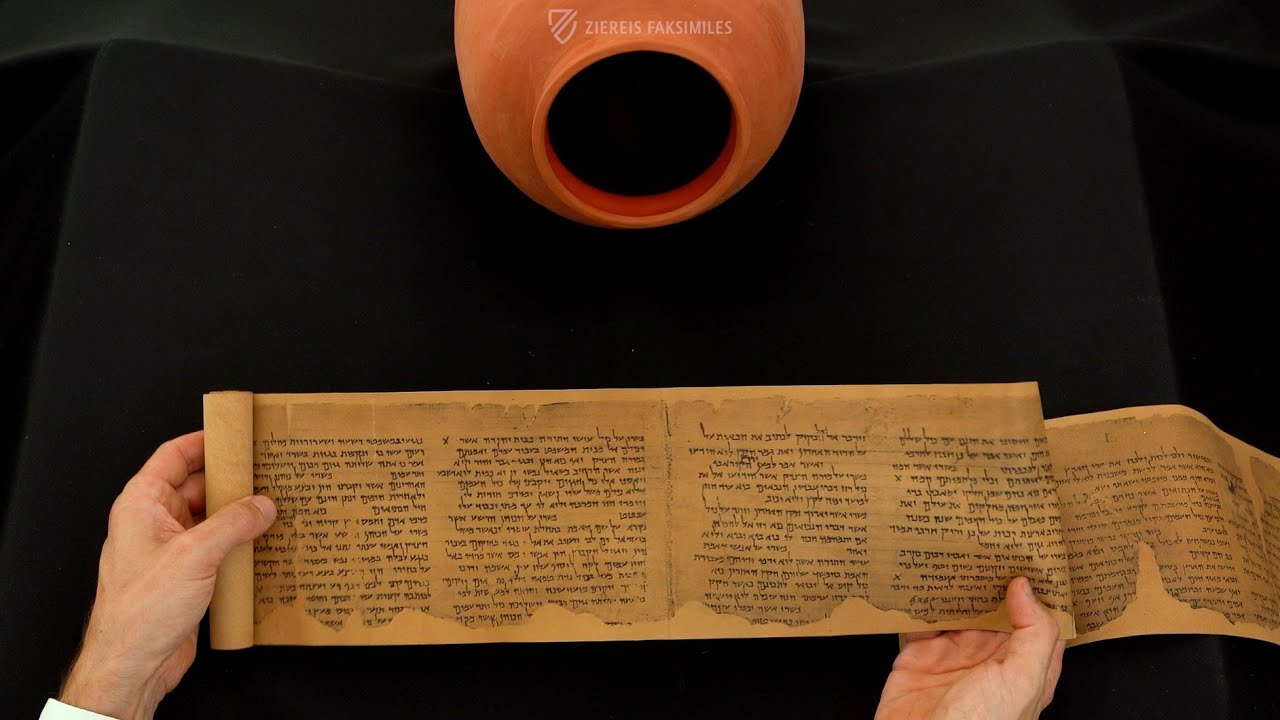

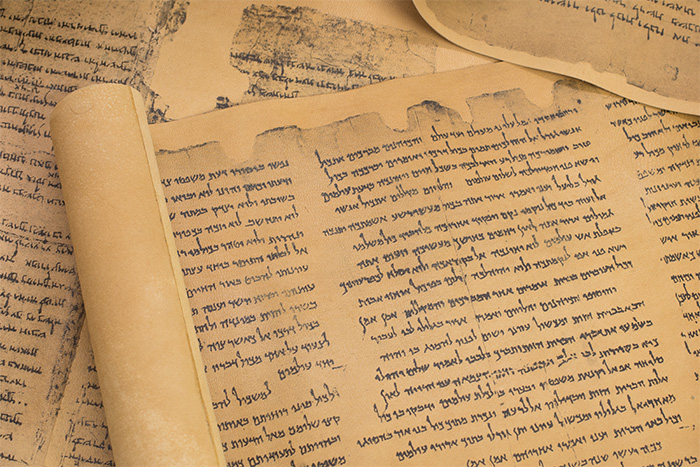

Many significant archeological finds were made in the course of the 20th century, but the greatest must be the Dead Sea Scrolls, ancient Hebrew manuscripts – some of which are 2,300-years old – preserved in sealed clay pots. They are the second-oldest surviving documents in Judaism and their discovery is one of the most important finds in the history of archeology. They were discovered between the years 1946 and 1956 in 11 caves near the Dead Sea, initially stumbled upon by Bedouin shepherds.

Experience more

The scrolls not only represent a magnificent survey of the fundamental texts of the Abrahamic tradition that are of great theological importance for Judaism, Christianity, and Islam alike, but also represent various forms of ancient manuscript production and exist on papyrus, parchment, and even one scroll made from copper.

To the facsimile

Although most of the scrolls only survived in fragments that had to be meticulously reconstructed over the course of decades, some managed to survive in a complete, albeit brittle condition. These manuscripts are priceless resources for scholars of manifold disciplines as well as being among the most important artifacts housed in the museums of the state of Israel.

A Greco-Roman Pharmacopeia

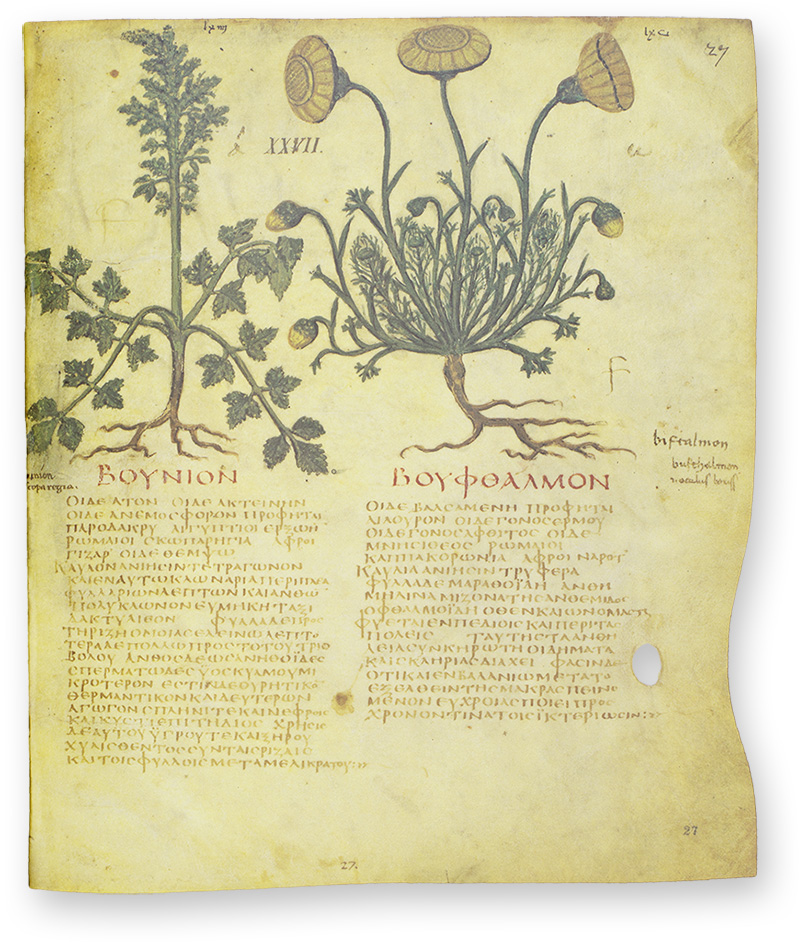

De Materia Medica is a Greek encyclopedia of herbal remedies and other medicines originating from the quill of Pedanius Dioscorides (ca. 40-90), a physician in the Roman army. The most important work of its kind for more than 1,500 years, this five-volume treatise by the Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist was upheld as the gold standard in both the Christian and Muslim worlds and is the ancestor of all modern pharmacopeias.

Unlike other works from antiquity that were rediscovered during the Renaissance, De Materia Medica never disappeared in the West and continued to be reproduced throughout the Middle Ages. The two oldest surviving illuminated manuscripts thereof originated from Byzantine workshops in the 6th and 7th centuries.

Named after its modern repository, the Vienna Dioscorides can be dated to ca. 512 and was created by skilled illuminators in Constantinople. The great esteem for and frequent use of the manuscript over the centuries is clearly visible from the numerous inscriptions and glosses in the margins added by later hands in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Persian, Turkish and Arabic.

To the facsimile

Also named after its modern repository, the Dioscorides Neapolitanus may have possibly been made in Naples or some other part of Southern Italy, which was under Byzantine control at the time. It is also beautifully illuminated in great detail, but is organized alphabetically in order to make it more efficient as a reference work and was written in a clear majuscule script that made it easier to read. These are two of the most important manuscripts in the history of medicine.

Ancient Virgil Manuscripts

Among the proud sons of Ancient Rome, few are more illustrious than Pubilius Vergilius Maro (70-19 BC), a poet during the reign of the Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BC – AD 14). Vrigil was chosen by Dante Alighieri (ca. 1265-1321) as his guide through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise in his famous Divine Comedy.

The first of his three major works was his Eclogues or Bucolics: ten compositions mostly consisting of conversations between herdsmen that range from the political to the erotic. Second came his Georgics, 2,188 hexametric verses of a largely agricultural nature but with a deeper philosophical meaning. Last but not least, the Aeneid, the foundation myth of Rome, traces the flight of survivors from the Fall of Troy to Italy, which the Emperor Augustus had published posthumously.

Three manuscripts from antiquity have survived and are stored in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, a 4th century fragment called the Vergilius Augusteus, the Vergilius Vaticanus (ca. 400) and Vergilius Romanus (ca. 500). The former contains the oldest surviving decorated initials while the latter two possess wonderful miniatures by Roman masters that represent a wonderful taste of art in Late Antiquity. These manuscripts are among the oldest and most coveted of the Vatican’s massive collections. The Virgil tradition was a cornerstone of the medieval curriculum and continues to be fundamental to the study of Latin today.

Roman Bibles

Two of the oldest surviving illuminated manuscripts of the Bible originated from Roman or Byzantine illuminators and represent some of the most important specimens of Christian theological history. The Ashburnham Pentateuch may have originated from as early as the 5th century, possibly created at the behest of the Roman Princess Galla Placidia (388-450) for her son, the future Emperor Valentinian III (419-455), but is dated by most historians to the 6th or 7th centuries. The Pentateuch is the first five books of the Old Testament, although the Book of Deuteronomy is now missing from this manuscript, which is famous for its full-page miniatures of Cain and Abel, Noah’s Ark, and more.

One of the proudest possessions of the Austrian National Library is the Vienna Genesis, which originated in the early 6th century. Likely created in Byzantine Syria with purple-dyed parchment, the text is written entirely in silver ink. The miniatures in both of these codices are brightly colored and represent fine examples of the idealized realism that was achieved through the meticulous labors of skilled classical artists.

An incredible degree of uniformity was achieved by the equally skilled scribes whose handwriting approached the precision of printed texts. In addition to their religious significance, these manuscripts are marvelous examples of illuminated manuscript production from Late Antiquity

A Roman Cookbook

Referred to popularly as “foodies” today, the equivalent term during the Roman Empire was Apicius, named after a famous 1st century gourmand named Marcus Gavius Apicius. The term has been applied to a work that is also known as De re coquinaria or “On the Subject of Cooking”. Often falsely attributed to Marcus Gavius, at least three different people are believed to be the author, who is thus referred to by the pseudonym Caelius Apicius.

The collection of 400 recipes was continuously appended until being completed in the 3rd or 4th centuries and thus represents a priceless inside look into patrician Roman dining practices, but also contains some more common dishes. It is organized into ten books covering different types of food in addition to general advice for cooking and housekeeping.

Sauce recipes received special attention, but full, multi-course meals are also described. Unfortunately, no manuscripts have survived from antiquity and the oldest specimens are Carolingian works created in the classical style. One of the oldest and most luxurious originated between 843 and 851 in the famous scriptorium of St. Martin de Tours and is stored today in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana under the shelf mark Urb. Lat. 1146.

The use of purple dyes and gold leaf indicate that the manuscript may have been commissioned as a gift to Charles the Bald (823-877), King of West Francia and a grandson of Charlemagne. This is a fine testimonial to attempts by the Carolingians to imitate the Romans as much as possible and thus derive legitimacy from their legacy.

A Hunting Book Worthy of an Emperor

To the facsimile

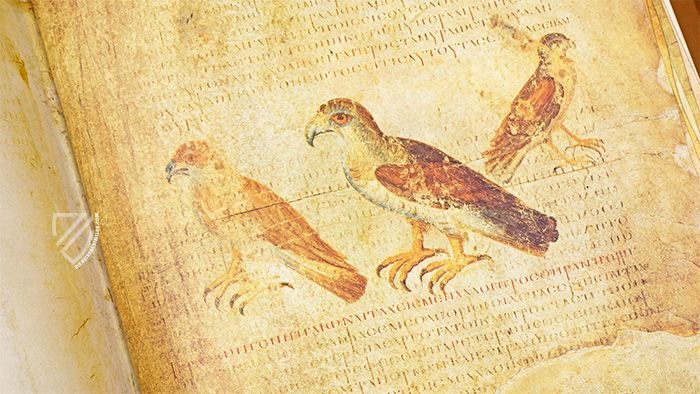

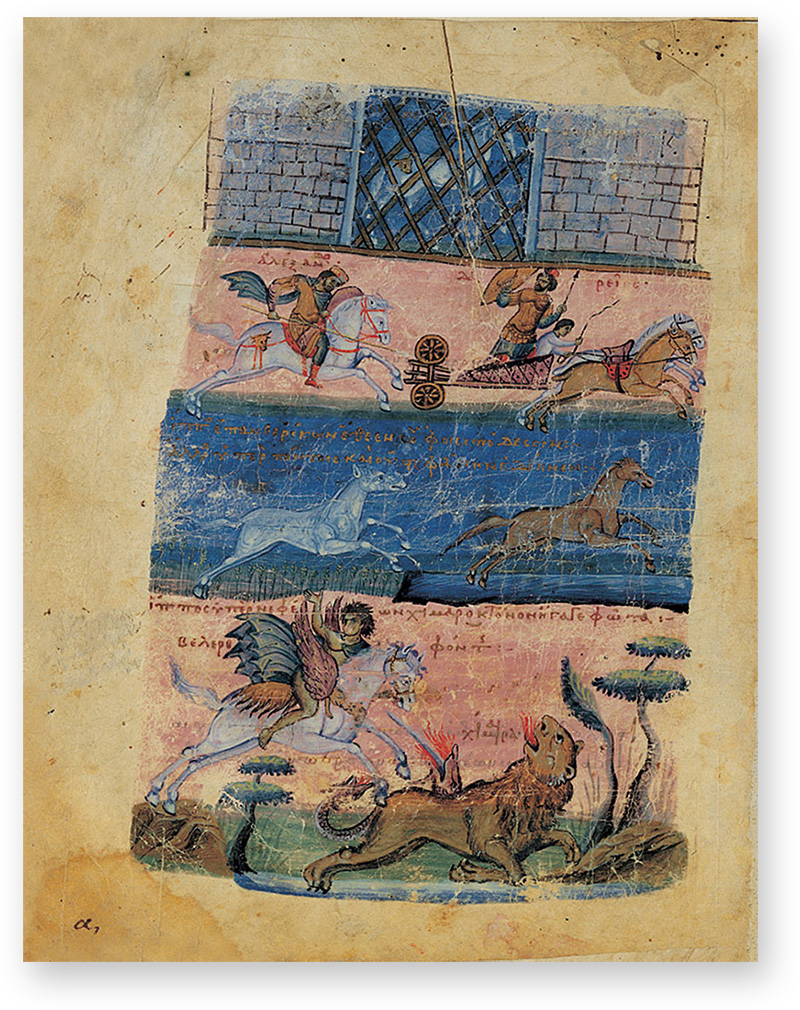

Often confused with the earlier, more famous poet Oppian of Anazarabus, Oppian of Apamea was a Greco-Roman from Syria who composed the Cynegetica or Treatise on Hunting and Fishing. The work can be dated to between 211 and 217 because it is dedicated to the Emperor Caracalla (188-217), a cruel tyrant whose solitary reign as emperor was cut short by his assassination.

Also remembered as a soldier-emperor, he spent most of his time with the army and thus would have dined regularly on wild game. The didactic poem, which reveals the author’s familiarity with the subject, was personally presented by Oppian to the Emperor, who praised the work.

To the facsimile

Although created in the 11th century, a splendid Byzantine manuscript stored today in Venice’s Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana under the shelf mark Cod. Gr.Z.479] (=881) wonderfully reproduced the classical style in which antique manuscripts of the work would have been rendered. This is because the work is a highlight of the so-called Macedonian Renaissance, when Byzantine art turned away from its iconographic character and returned to the more natural realism of classical art.

157 brightly colored miniatures illustrate the informative text with entertaining scenes of hunters and fishermen employing hounds, horses, and various equipment to catch a wide variety of fish and game. At the behest of Cardinal Bessarion (1403-72), the text was completed by Georgios Trivizias, a priest of the Greek community in Venice, before it was donated along with the rest of Bessarion’s extensive library as a gift to the city of Venice in 1468.