Bestiaries

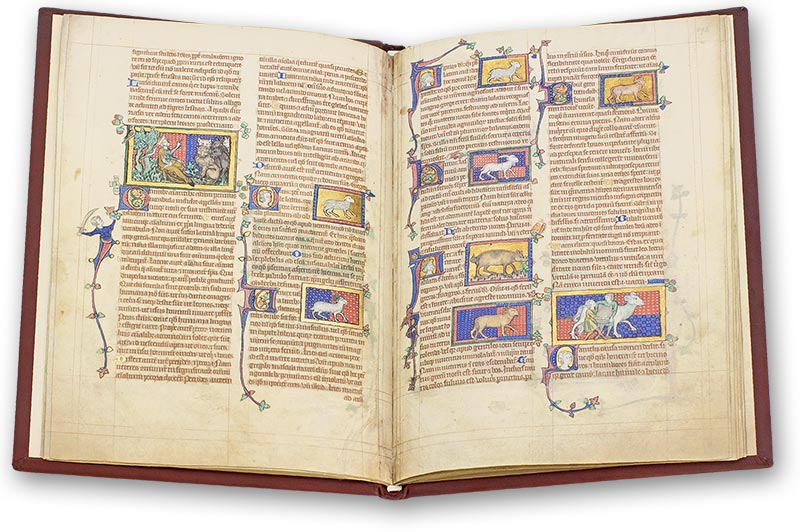

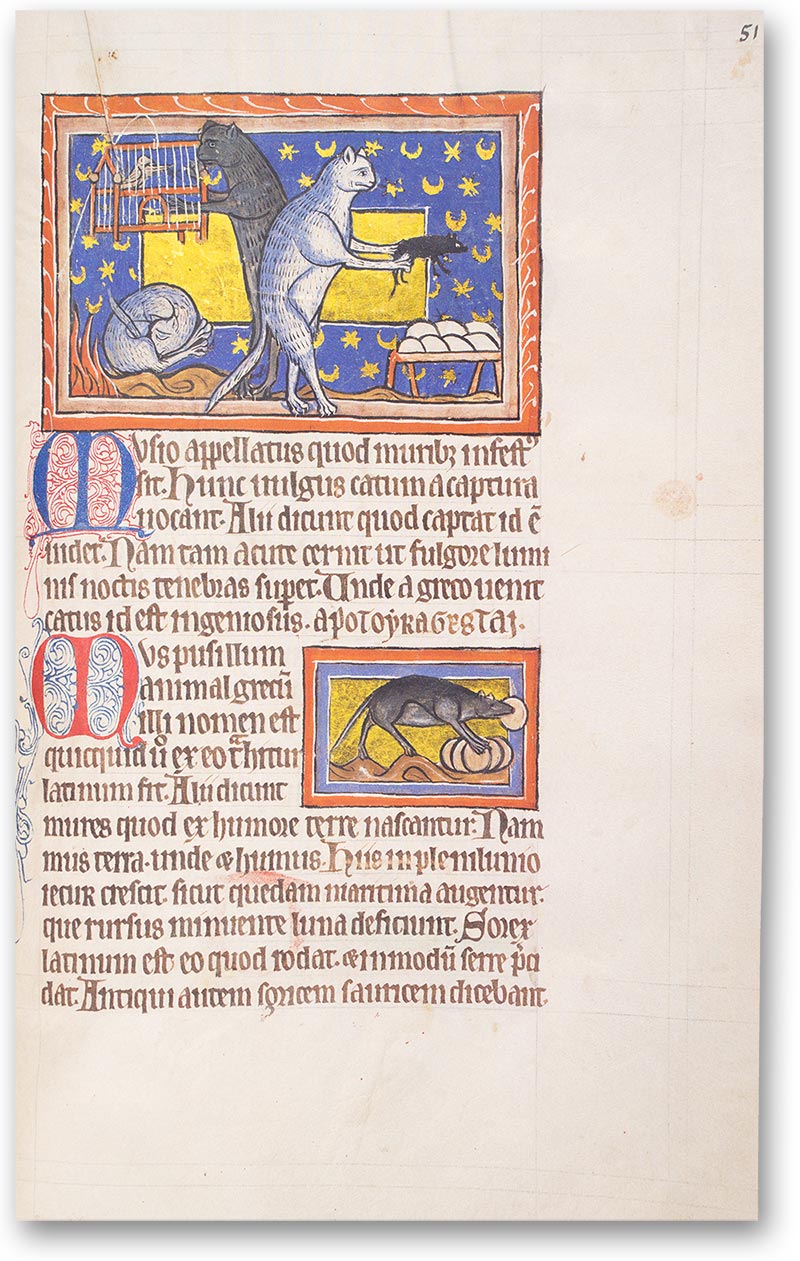

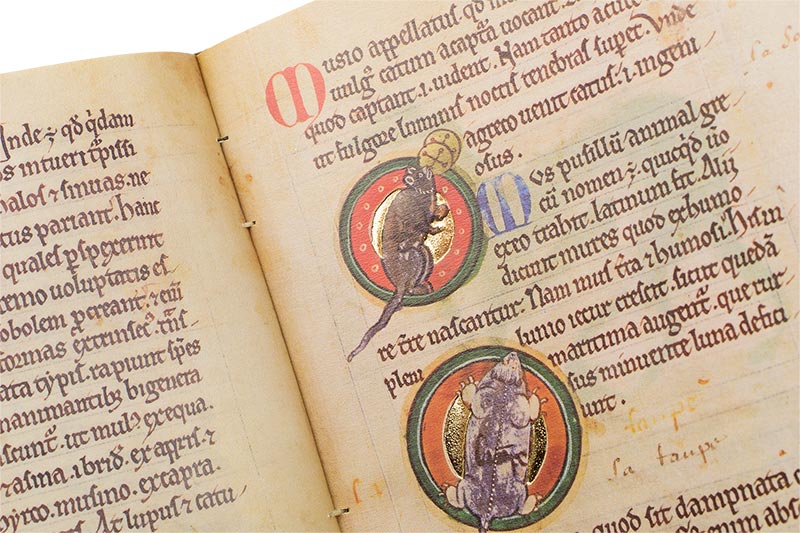

Among illuminated medieval manuscripts, the bestiary or “book of beasts” was second only to the Bible and book of hours in popularity. The depiction of dozens or hundreds of beasts like those found in the Peterborough Bestiary offered great opportunities for illuminators to exercise their artistic creativity.

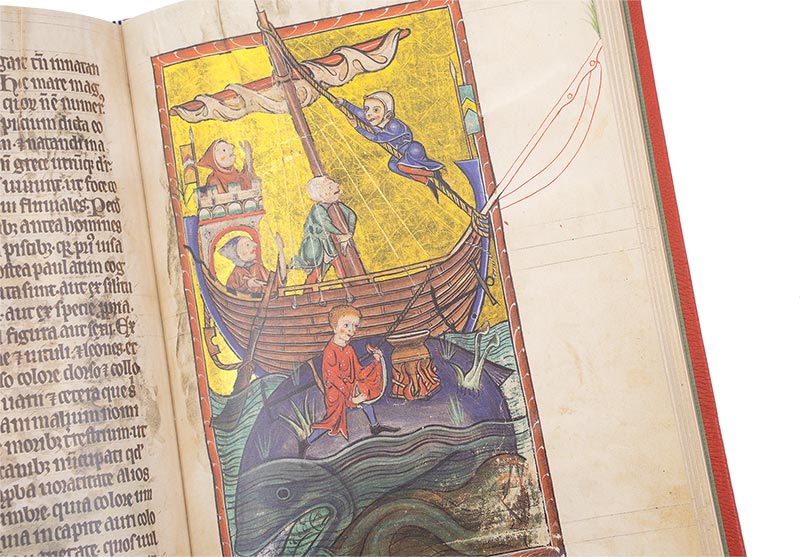

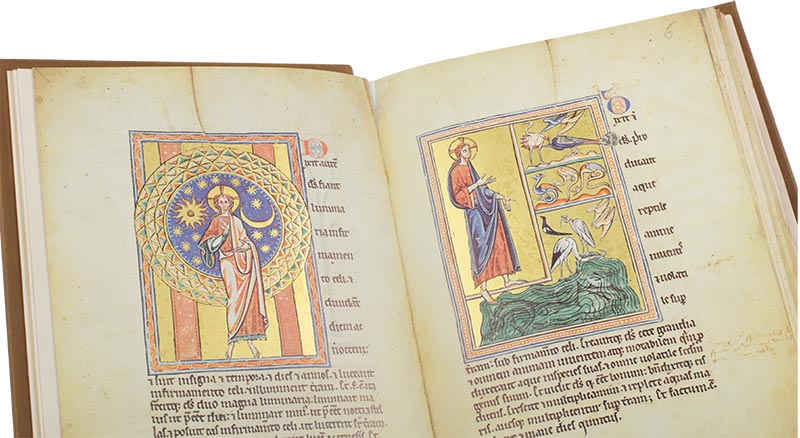

Some, like the Oxford Bestiary, made extensive use of precious gold leaf. However, these were not merely proto-zoological texts, animals were treated as allegorical creatures associated with a moralizing lesson from Christian theology.

This genre of medieval manuscript is rooted in antiquity and bestiary manuscripts represent some of the most popular, artful, and fascinating medieval texts to survive today. Thus, bestiaries offer a unique glimpse into the mindset and outlook of medieval Europeans. It is for all of these reasons that bestiaries were so popular during the Middle Ages, and continue to be some of the most fascinating specimens of medieval art today.

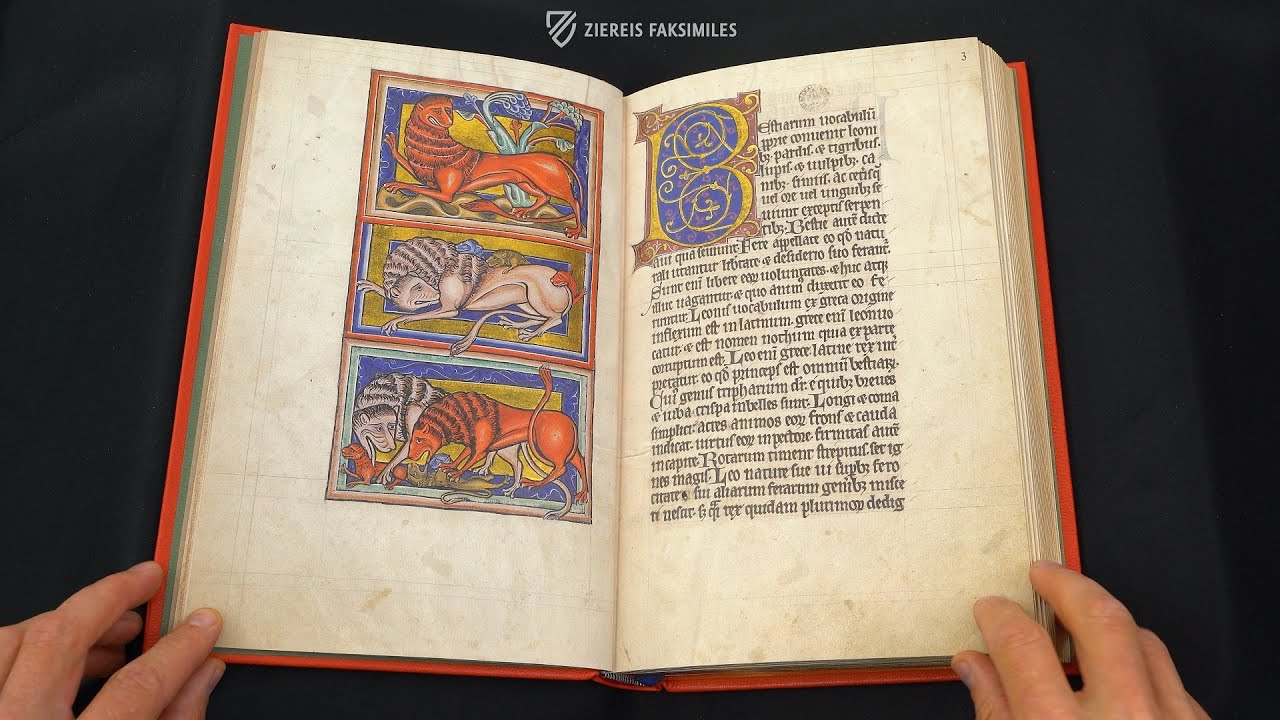

Demonstration of a Sample Page

St. Petersburg Bestiary

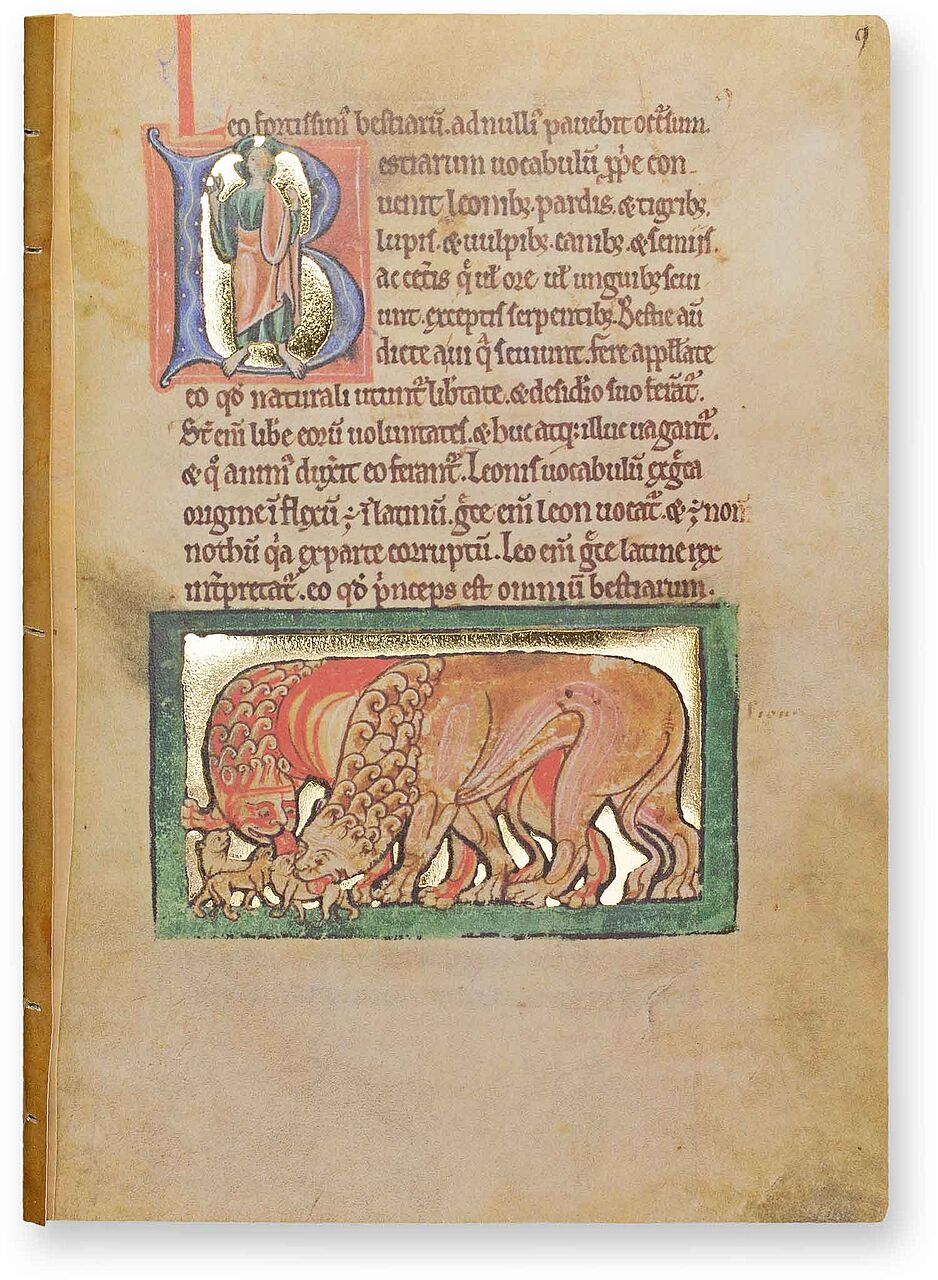

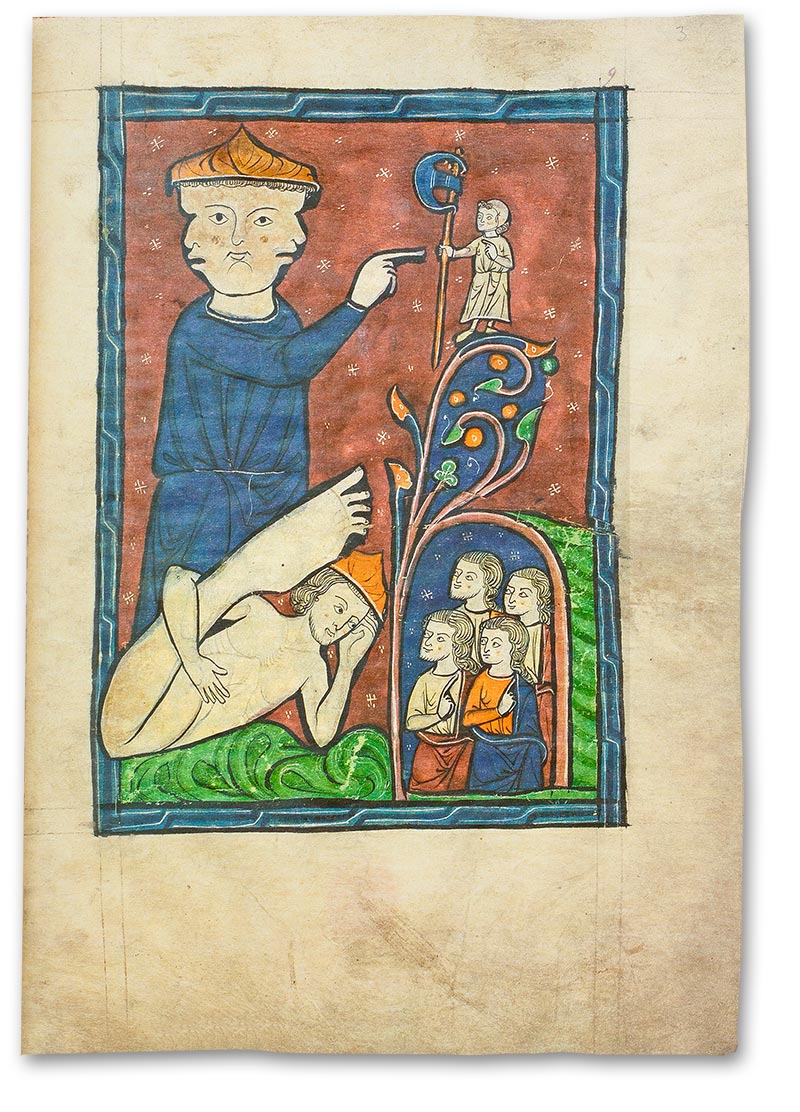

Family of Lions

As the ‘king of the beasts’, the lion is the first animal featured in this splendid 12th century English bestiary. It follows an image cycle of the history of Creation, including Noah gathering the animals for his ark. The miniatures are iconographically unique with splendid gold grounds and are some of the earliest attributed to the Gothic style.

The artist’s lack of familiarity with lions is evident from the fact that both parents are depicted with manes and was likely working from a model, as was typical. Nonetheless, they are depicted with loving faces as they lick their cubs. Above, Christ stands barefooted in the “B” initial giving the sign of the benediction as though the capital letter were a door into the shimmering golden divine.

A Compendium of Beasts

To the facsimile

“But ask now the beasts, and they shall teach thee; and the fowls of the air, and they shall tell thee: Or speak to the earth, and it shall teach thee: and the fishes of the sea shall declare unto thee. Who knoweth not in all these that the hand of the LORD hath wrought this? In whose hand is the soul of every living thing, and the breath of all mankind.”

Book of Job 12:7-10

To the facsimile

The bestiary or “book of beasts” represents one of the most entertaining and beloved genres of medieval manuscripts, one which naturally lends itself to a wealth of imagery that allowed for the full artistic range of the skilled illuminator to be expressed. The quality of the images depended on the widely-ranging skill levels of the artists, from simple drawings to more refined works of art executed with rich colors and gold leaf.

To the facsimile

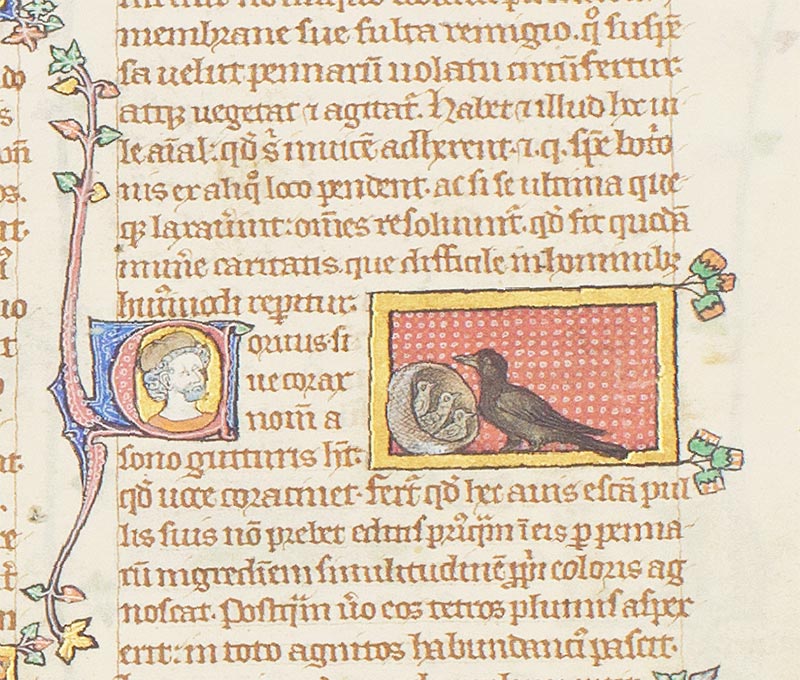

Bestiaries combined Christian allegory with quasi-zoological information on the animal in question, including rocks and minerals – oysters were considered to be a kind of living rock that produced pearls. These works were rooted in the belief that God arranged the natural world with the intent of instructing humanity, as per the quote above. For example, the Peterborough Bestiary features an illustration of a crow representing the love and worry experienced during childrearing. Bestiaries and the lessons they contained are an important glimpse into the medieval mindset.

Roots in Antiquity

To the facsimile

Like so many medieval book genres, bestiaries have their roots in antiquity. Animal allegories – Aesop’s Fables being the most famous – were a popular metaphor for classical authors. An early example of an animal-allegory-text is the Physiologus, written in Greek in Alexandria in the 2nd or 3rd century. It was translated into most European languages and was the most popular book genre during the Middle Ages after the Bible.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The rich imagery of the bestiary had broad appeal to a society wherein perhaps less than 5% of the population could read Latin with any fluency, the only officially written language for most of the Middle Ages. Preachers used bestiaries in sermons for the instruction of the laity who were illiterate to varying degrees but would nonetheless remember the moral lesson associated with the beast in question. Therefore, these manuscripts were not meant to be merely informative or entertaining but instructive as well.

A Medieval Favorite

To the facsimile

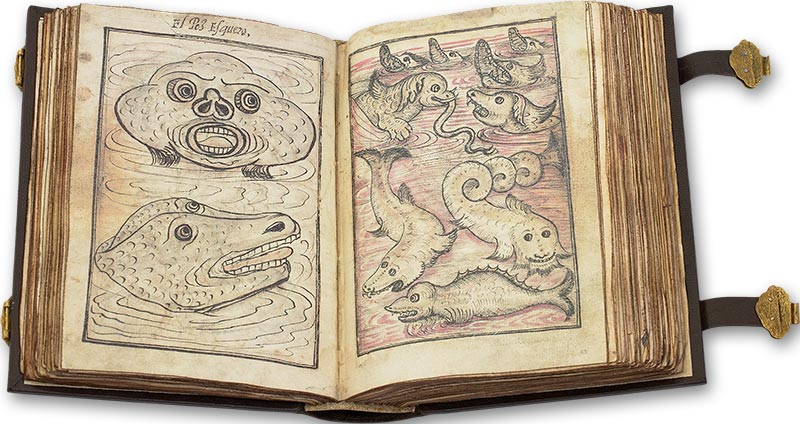

Although the bestiary was second only to the Bible in terms of the number of manuscripts produced during the Middle Ages, its production was largely limited to the lands of the Normans in England and Northern France beginning in the 11th century and peaking in the 13th century. They were mostly in Latin, but also vernacular, French in particular, although there are some in Italian and one in Spanish – the Bestiary of John of Austria (ca. 1570), which belonged to Juan de Austria, the bastard son of Emperor Charles V, remembered by history as the victor of the Battle of Lepanto (1571).

To the facsimile

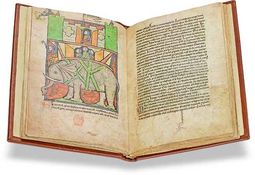

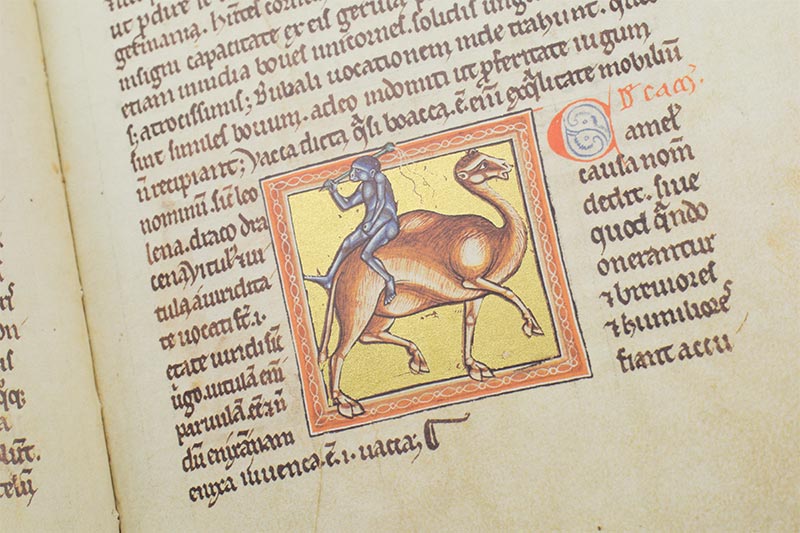

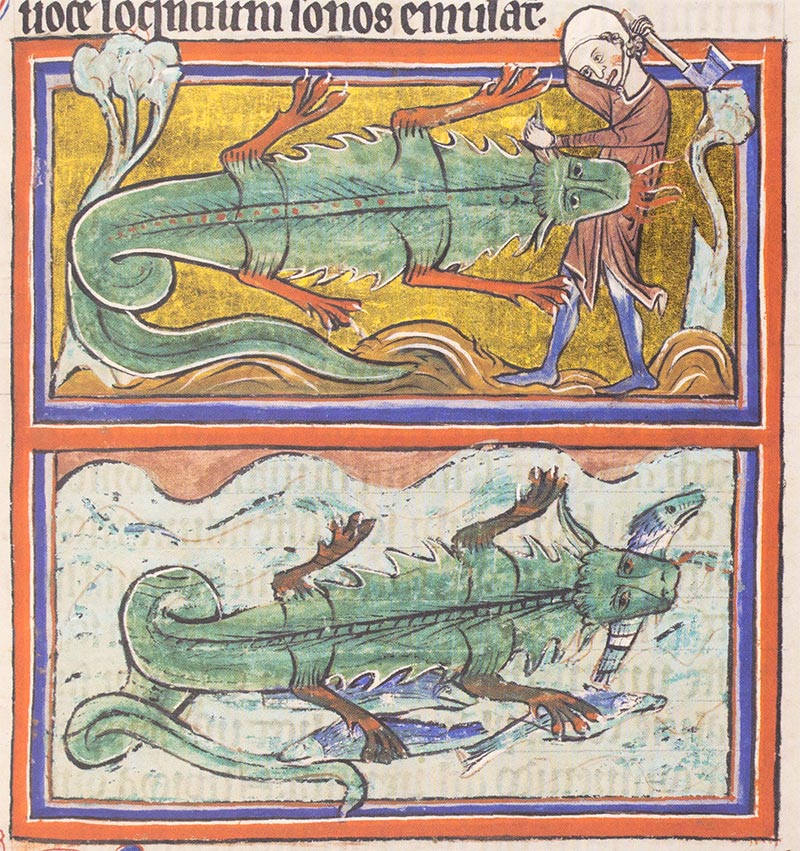

The realism of the depictions in any bestiary would be limited by the fact that the illuminator would have probably never seen the majority of the animals and therefore based their depiction on animals that they were familiar with. For example, the Westminster Abbey Bestiary features a famous depiction of a war elephant with a castle on its back.

To the facsimile

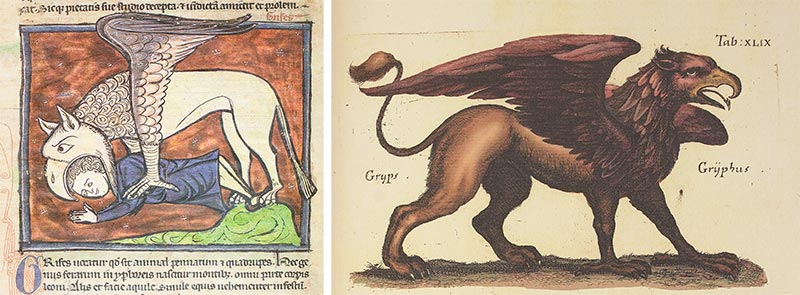

Although mythical beasts were listed alongside more mundane ones, it is a modern prejudice to assume that all medieval people thought that unicorns, dragons, and griffins existed – some did for sure, but many understood them as being metaphorical.

To the facsimile

Full bestiary cycles are featured in the Queen Mary Psalter and the Isabella Psalter. Images of beasts were found in the margins of other manuscripts, and they were carved into wood and stone in churches and monasteries, painted in mosaics, and woven into tapestries. The ever-present nature of these images was upsetting to some like St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote ca. 1127:

"What profit is there in those ridiculous monsters, in that marvelous and deformed comeliness, that comely deformity? To what purpose are those unclean apes, those fierce lions, those monstrous centaurs, those half men, those striped tigers, those fighting knights, those hunters winding their horns? […] In short, so many and marvelous are the varieties of shapes on every hand that we are tempted to read in the marble than in our books, and to spend the whole day wondering at these things rather than meditating the law of God. For God’s sake, if men are not ashamed of these follies, why at least do they not shrink from the expense?"

From Bestiary to Encyclopedia

To the facsimile

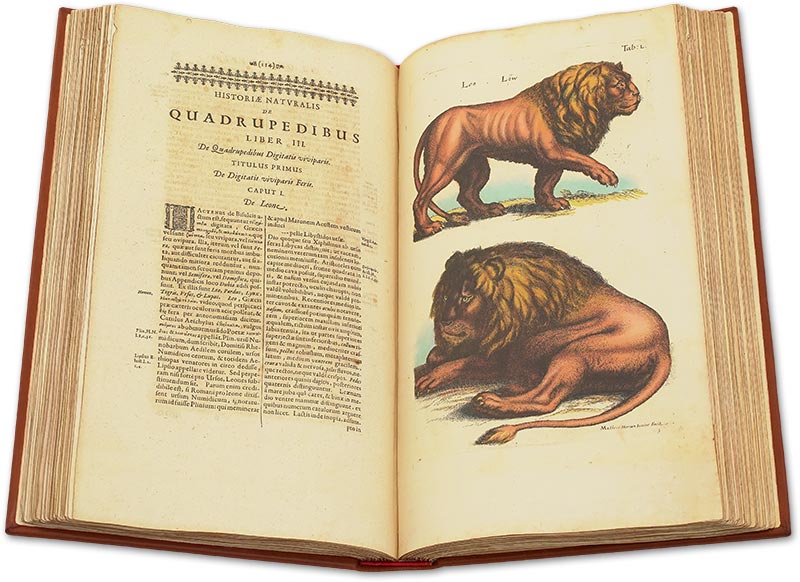

The emergence of encyclopedias in the 13th and 14th centuries marked the end of the bestiary because the new texts lacked allegorical content. These proto-scientific texts sought to do away with any erroneous information, but often threw out the baby with the bathwater. Some of the correct observations of the medieval bestiaries, like the migration of birds, were thrown out by Early Modern natural philosophers along with the more erroneous claims of these texts, only to be confirmed later by modern science.

To the facsimile

Medieval bestiaries incorrectly but adorably stated that bear cubs are born unformed and have to be licked into shape by their mother (another metaphor for the responsibilities of parenthood), that crocodiles weep after eating a person, and oxen are not only strong but can predict the weather, although how they are supposed to impart this information is not clear. They correctly surmised that the number of fish species is beyond counting (we find more every year) and observed that pairing a patient suffering from internal wounds with a young dog had an efficacious effect – a medieval therapy dog.

To the facsimile

Although they lacked such whimsical insights, the encyclopedias of the 17th century, such as the Historia Naturalis by John Jonston, possessed incredible detail. It is divided into volumes like De Arboribus et Fructibus, De Avibus, and De Insectis and forms the foundation of modern zoology. Modern depictions of animals in literature and the attention paid to the ecological lessons of medieval texts attest to the ongoing fascination we have with the beasts of the field, the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea.