Benedictines, Franciscans, Dominicans, and many more: Monastic Orders of the Middle Ages

A religious order is a community of men or women who live according to certain, fixed rules and very often wear a religious habit. Three principles of life are central and decisive for their spiritual orientation: celibacy, poverty, and obedience. They are called the evangelical counsels because they are characteristic of Jesus’ way of life as described in the Gospels. These three principles are deliberately called "counsels" and not "rules": they are not binding obligations for all Christians, but rather recommendations (or counsels) that every Christian can follow with different intensity.

Order members have opted for a rather intense, though not radical interpretation of these counsels since they solemnly commit themselves to them after a trial period in a so-called profession until the end of their lives. This commitment can be understood as an attempt to come as close as possible to the way of life of Jesus.

The Predecessors of Monasticism in the Desert

To the facsimile

But how did this special way of life come about? The first predecessors of the religious orders as we know them today can be found in the early centuries of Christianity in the Egyptian and Syrian deserts. Men who wanted to take the message of Jesus and his life particularly seriously went there and found a radical way of expressing it: they ascetically strove to become as free as possible from their own needs, lived secluded and sexually abstinent in the desert, and fasted often – not least to draw attention to the limitations of all earthly and transient things.

To the facsimile

If these men lived completely alone in the desert, they were called hermits (Greek eremos, desert); some joined together with others there and were then called koinobites (Greek koinos, together). The withdrawal from society by men who are called anchorites (Greek: anachoreo, to retreat) also contains a socially critical component. With their way of life, which was unusual even by the standards of the time, they questioned the rules and values that applied in society. One of the most famous anchorites, frequently depicted in art, is St. Anthony (ca. 251-356) (see e.g. Isenheim Altar).

The Benedictines

To the facsimile

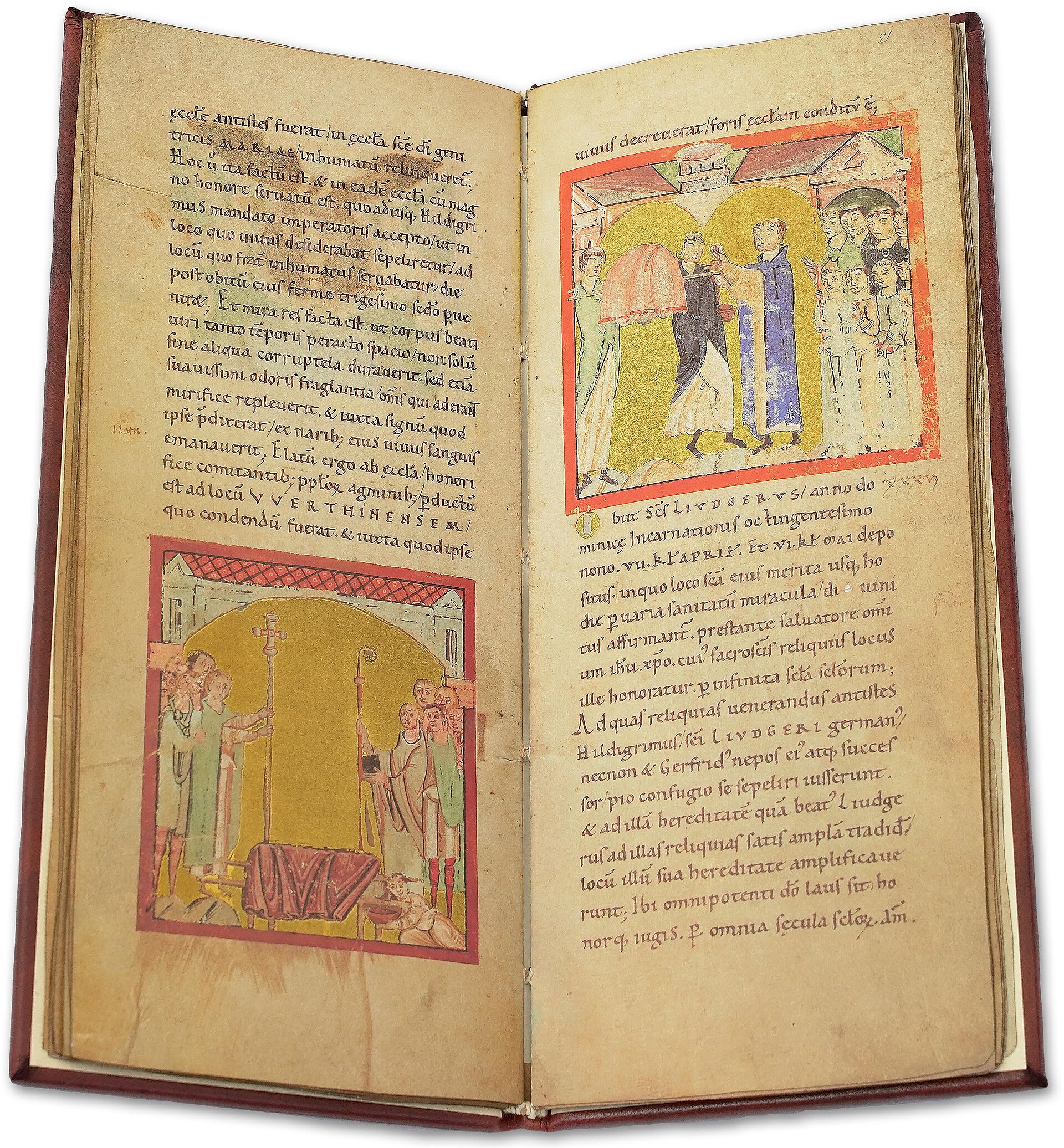

Both components, the withdrawal from society as well as community life, are found in the order that may be regarded as the oldest, most traditional and most effective of Christianity: the Benedictines (order abbreviation OSB for Ordo Sancti Benedicti). They are still easily recognizable today by their completely black habit.

To the facsimile

The birth of the Benedictines and thus of monasticism as we know it today occurred in the year 529. Emperor Justinian closed the Academy of Plato in Athens, which had been the epitome of philosophy and pagan education for more than 900 years. In the same year, Benedict of Nursia founded the first Benedictine monastery on Monte Cassino near Naples. With this he laid the foundations for more than a thousand years of history of monastic Christian education. In this respect, this year symbolizes the not entirely conflict-free transition of pagan education into Christian hands.

Nevertheless, it was by no means Benedict's goal to create an educational institution. Rather, he wanted to form a community of men who lived according to the principles of the Gospel, which he concretized in his famous religious rule, the Regula Sancti Benedicti, for daily cohabitation. This rule not only became the basis for many later orders and remains unchanged in the Benedictine order today, but also shows his comprehensive wisdom and knowledge of human nature.

The socially critical aspect of the Desert Fathers also remains a part of it: thus the hierarchy of the new community (for example, at meals or in church services) was based on the age of entry of the respective monk – the class distinctions that so strongly marked the Middle Ages play no role in Benedict's Rule.

To the facsimile

The famous principle "Pray and work!" (Ora et labora!) does not originate from Benedict himself in this formulation. It does, however, make it clear that Benedictine monks live contemplatively, i.e., they devote themselves to prayer in a contemplative manner, withdrawn from the world; at the same time, however, each monastery must be economically self-sustaining, in that the monks earn their own living.

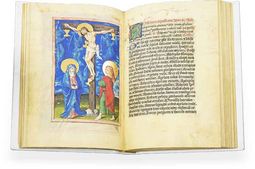

The regular daily routine, which was precisely divided between the original seven daily prayers, facilitated a lot of productive activity. Monasteries have thus played a historic role in land clearing and reclamation that is not to be overestimated, as well as later as an educational institution. Last but not least, we owe the majority of medieval manuscripts to the persistent and gifted hands of industrious monks.

Abuses and Reform Movements

To the facsimile

In the course of the centuries, the radical orientation towards Jesus' way of life fell into oblivion again and again in monasticism, and a frequently problematic relationship with the secular rulers arose, who not only acted as benefactors of monasteries, but often massively intervened in the fate of the monastery in their own interest, e.g. in the appointment of the abbot. The monks themselves also became lax in their way of life, living in part no longer from their manual labor but from donations and endowments, and indulging in a licentious way of life that no longer had anything to do with the original founding idea of Benedict of Nursia.

To the facsimile

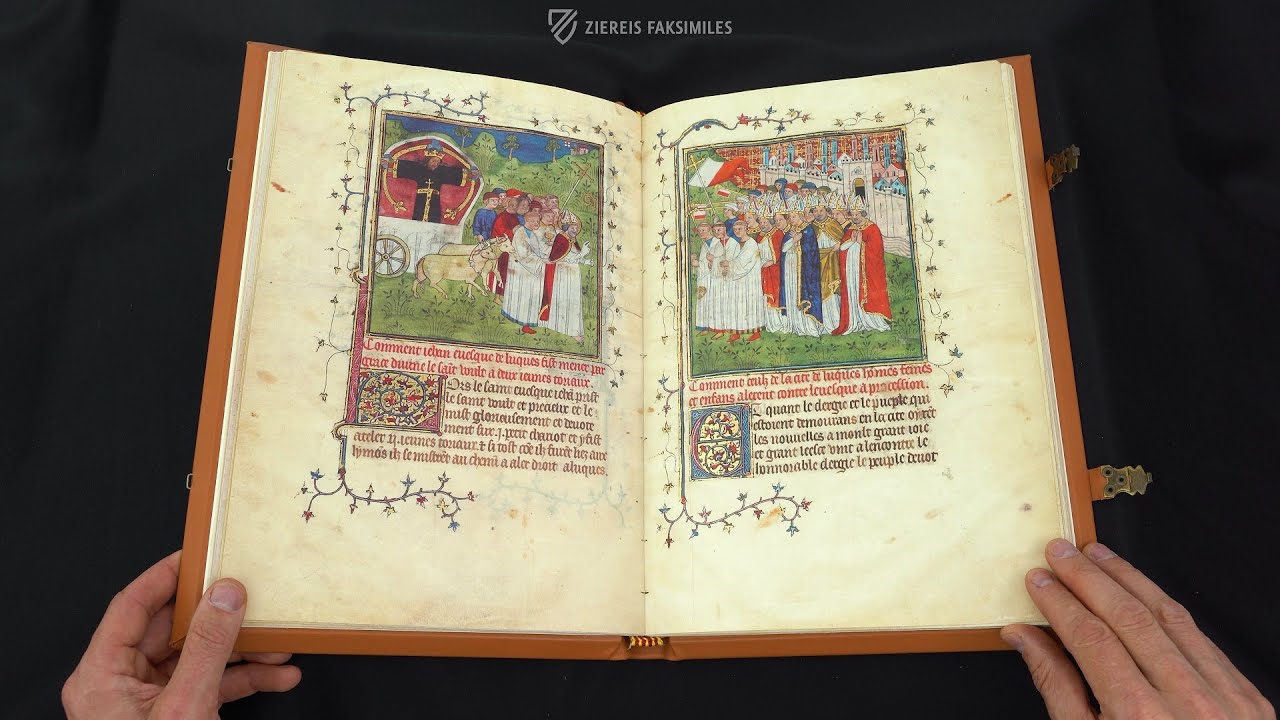

Various reform movements, of which Cluny is one of the most important, reacted to these developments within monasticism. It was structurally favored by the founder of the monastery, Duke William I of Aquitaine (875-918), who placed it directly under the pope after its foundation in 910. In this way, Cluny and all the monasteries associated with it throughout Europe including the German monastery of Hirsau, which existed ca. 1200, emphasized their independence from secular rulers. The reform movement took advantage of this by calling for the strict observance of the Rule of Benedict in all monasteries by suppressing excesses (including the liturgical kind), and by recalling once again the limitation of all material goods.

The strengthening of the papacy in the Investiture Controversy and in the disputes with the nobility of the city of Rome also became a concern of the Cluniac reform and shows its overall ecclesiastical importance. In the course of the following centuries, however, similar excesses took hold in Cluny, against which the reform movement itself had originally fought. This was evident, for example, in the construction of the church known today as Cluny III: it remained the largest church in Christendom until the consecration of St. Peter's in Rome in 1626!

The Cistercians

To the facsimile

The excesses in Cluny regarding the way of life and the construction of churches and monasteries were a trigger for the foundation of another reforming order that set standards in church and society: the Cistercians (OCist). Robert of Molesme laid the foundation stone for this order in 1098 and Stephan Harding gave it its constitution shortly thereafter. However, without St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) this new order (recognizable by its white undergarment with the black scapular above it) would most likely not have survived the early years in terms of personnel alone.

Due to his captivating and charismatic manner, Bernhard not only brought almost 30 relatives and friends into the order when he joined, but also founded 165 monasteries in the course of his life, which made up half of all the Cistercian institutions existing at the time. His ability to sway the masses, which e.g. became noticeable in his sermons for the Second Crusade (1147-1149), can be explained in part by Bernhard's radical nature: at the beginning of his monastic life, he overdid asceticism to such an extent that he contracted a serious lifelong stomach ailment.

To the facsimile

At the same time, it was precisely this uncompromising attitude that prompted many monks and nuns to consciously return to the radical discipleship of Jesus from early monasticism. Though of a strictly contemplative orientation, the monastic was no less passionately involved in political, social, and church affairs outside the monastery. He was well aware of the conflict of roles that arose from this. In a letter he once described himself as a "chimera of my generation", i.e. a hybrid being, since he was not a layman due to his habit, but because of his way of life he was also no longer a monk.

To the facsimile

All the orders mentioned so far belong to the so-called monastic orders, also known among religious orders as the monastic way of life. It is characterized by the fact that they live in a cloister, i.e. a monastery, which they do not leave in principle or only if necessary, and concentrate entirely on contemplation and the common Liturgy of the Hours in addition to the work necessary for survival.

To the facsimile

In contrast to monasticism in the narrower sense, a different form of communal living emerged in the 11th century, which is oriented towards the communal life of monasticism, but at the same time sets its own accents in such a way that these religious orders are no longer considered to be classical monks: the Augustinian canons regular, among others.

The Augustinian Canons Regular

To the facsimile

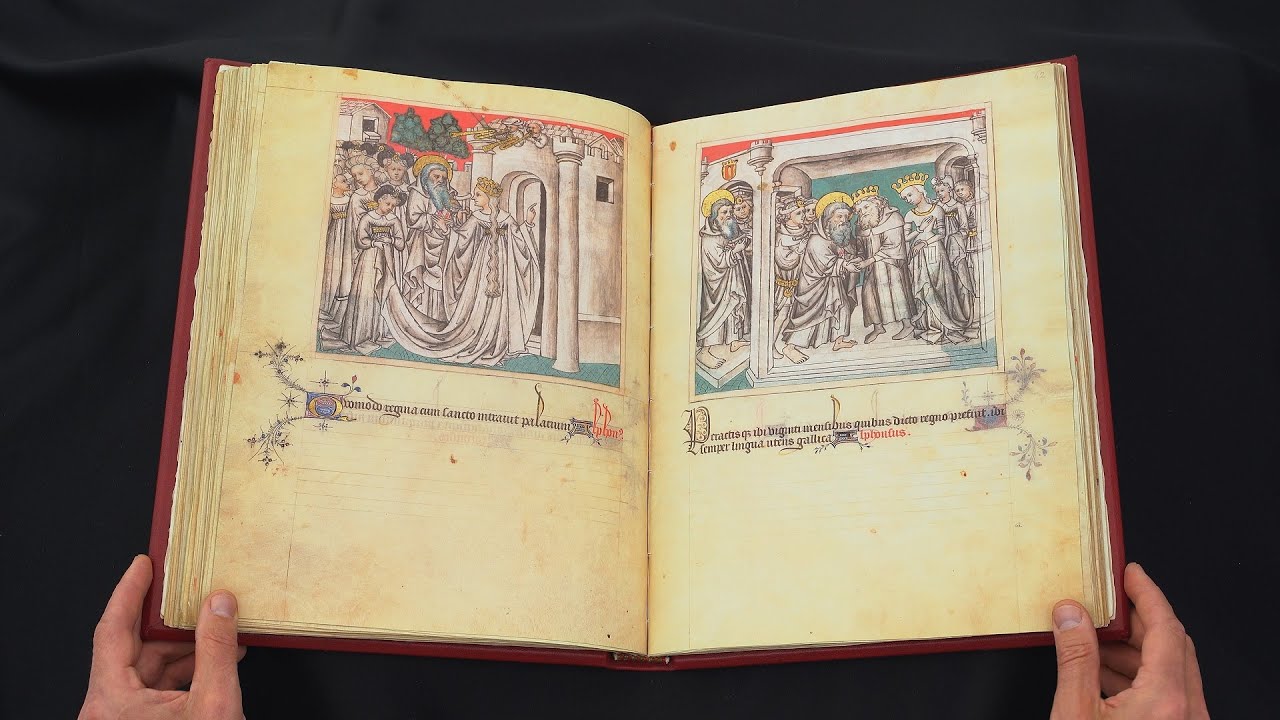

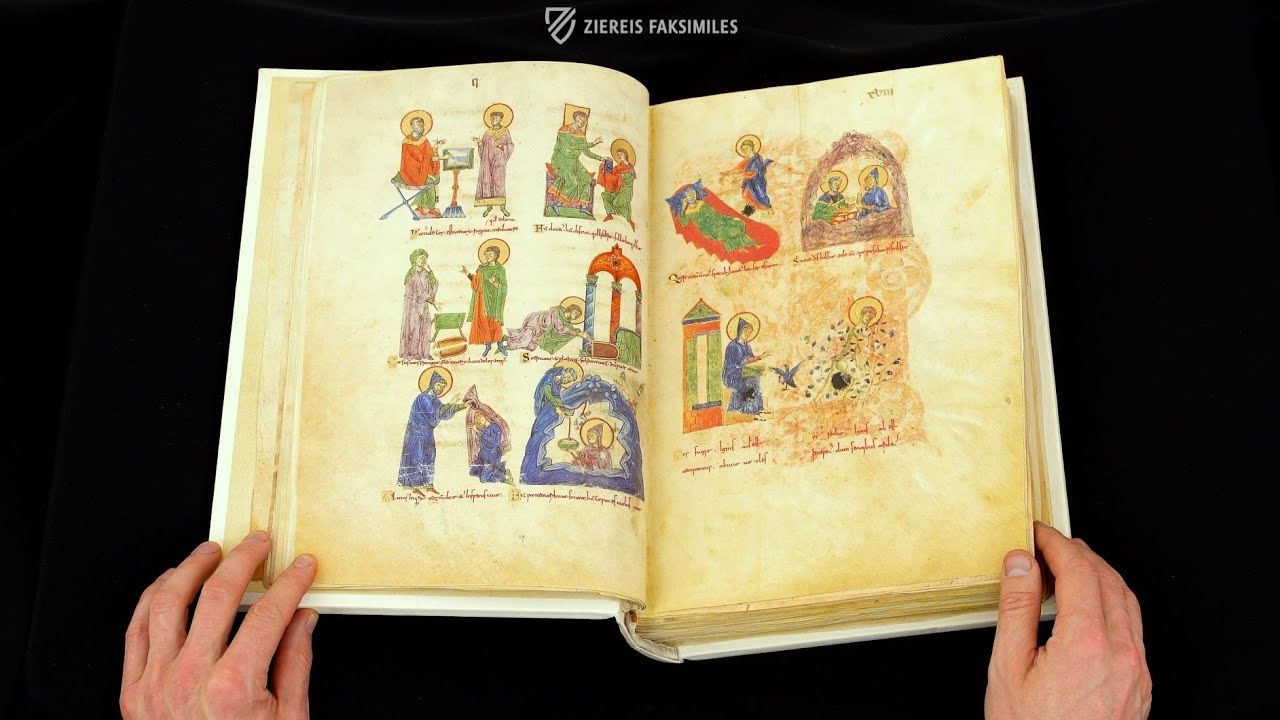

The Augustinian canons regular originated from canons, i.e. consecrated men of the Catholic Church, who perform their liturgical service at a cathedral, basilica, or religious church and gather not only to celebrate the Eucharist, but also at the so-called canonical hours, the Liturgy of the Hours. The Augustinian canons belong to the regular canons, because they follow the Rule (regula) of St. Augustine (354-430) in their communal life and therefore, like monks, renounce private property completely.

To the facsimile

The lasting difference to monks, however, is that they do not live from the work of their hands, but devote themselves entirely to pastoral care and education, which is hardly part of the profile of classical monastic orders. According to the Rule of St. Augustine, women also lived together in cloisters; they are then called Augustinian canonesses regular (cf. the Guta-Sintram Codex).

The Premonstratensians

To the facsimile

The Premonstratensians are also not monks in the original sense, but canons founded as a religious order in 1120 by Norbert of Xanten (1085-1134) that also lives according to the Rule of St. Augustine. They can be recognized by their snow-white habit. A special feature of the founding of the order is that men and women originally lived together in so-called double monasteries.

To the facsimile

However, this double structure was already dissolved in the 12th century in favor of independent male or female monasteries. In addition to the consecrated canons (canonici), there were also so-called lay brothers (conversi) in this order who contributed significantly to the remarkable agricultural development through their manual labor, especially during the Christianization of Northern Germany.

The Mendicant Orders

To the facsimile

The best-known orders, which are no longer called monks like e.g. Benedictines and Cistercians, are the so-called mendicant orders. Among them are the Franciscans, the Dominicans, the Carmelites, and the Augustinian hermits. In the 13th century, the reason for their foundation was once again due to the grievances, undesirable developments, and tendencies towards secularization in the church, especially with regard to questions of property and wealth.

To the facsimile

In the face of sometimes excessive wealth and extensive possessions of many monasteries and dioceses, the mendicant orders again radically emphasized the evangelical counsel of poverty and therefore wanted to live entirely from alms and donations, at least at the beginning of their foundations. This characteristic evaporated relatively quickly, however, and there were even repeated disputes within the new religious orders, e.g. about whether the monastic community as a whole was allowed to own property and how the counsel of poverty was to be understood exactly.

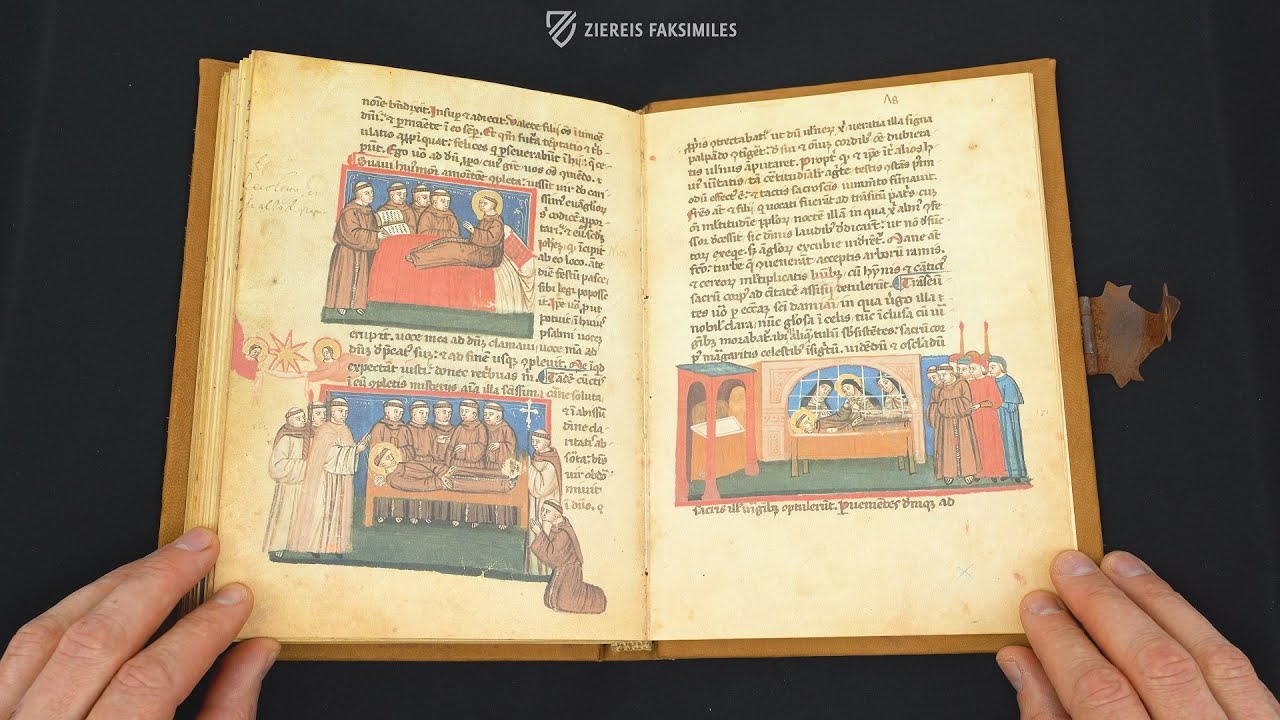

The Franciscans

To the facsimile

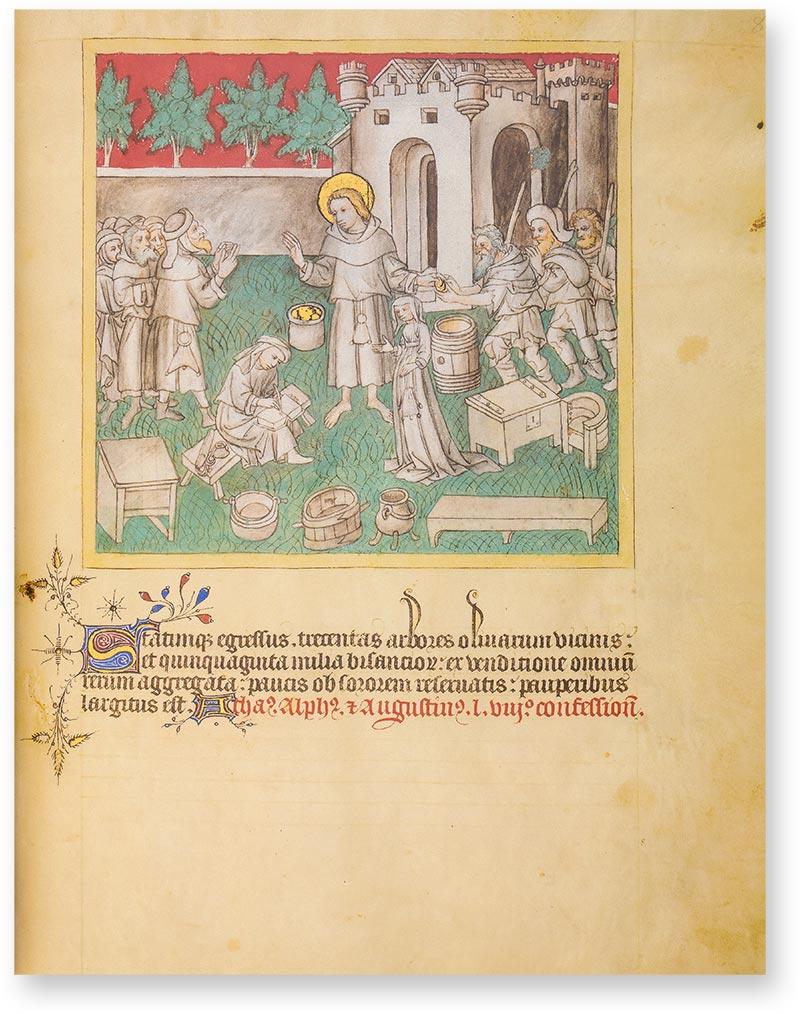

The Franciscans initially found radical answers to these questions. In the person of their founder, St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226), the effort to establish an intense relationship with God was combined in a paradigmatic way with the attempt to live in strict poverty. After he had a vision from Jesus in 1205 in front of the cross in the church of San Damiano, which still exists today, his unsavory way of life in complete poverty led to serious conflicts with his wealthy family, finally resulting in a break with them.

To the facsimile

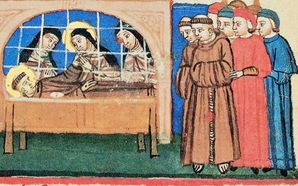

He found his new home in numerous followers and friends who joined his unusual way of life in order to live completely according to the Gospels. In collaboration with St. Clare (1194-1153), who wrote a special rule for the female branch, the new Order of Franciscans, who initially called themselves fratres minores as an expression of their modesty, came be called Friars Minor. In the course of the centuries there were differentiations and splits.

To the facsimile

Today there is a particular branch of the order classified as Minorites, whose brothers are allowed common property and who can be recognized by their black habit. In colloquial language they are therefore called Black Franciscans, the abbreviation OFM Conv refers to their other name, Conventuals. In contrast, the friars called Observants (with the abbreviation OFM Obs.) wear a brown habit and strive for a particularly strict interpretation of the Franciscan rule. The Capuchins split off from them in 1528, which they made clear by the changed form of their brown habit.

The Dominicans

To the facsimile

A religious community that came into being almost at the same time as the Franciscans are the Dominicans, founded by the Spaniard Saint Dominic (1170-1221). Through his contact with the Cathar movement, which was particularly widespread in southern France, Dominic noticed how necessary both a good theological education and an authentic way of life were to put a stop to the extremist currents of the time. For this reason, he did not use a horse as a mount for his preaching journeys and initially lived by begging, which was not without danger because of the feared proximity to the way of life of heretics.

To the facsimile

However, Dominic succeeded in gaining papal recognition and the order found its main purpose in spiritual welfare and preaching. This is also expressed in the self-designation as Ordo praedicatorum, i.e. as the Order of Preachers (brothers). The profound theological education, which is indispensable for good preaching, brought forth its own religious colleges and above all several brilliant theologians, among many others the most important theologian of the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). In the process, scholarly disputes between members of the Franciscan and Dominican orders arose time and again. Dominicans can be recognized by their white habit with white cingulum; the choir mantle for the liturgy is black.

The Carmelites

To the facsimile

The Carmelites show in their origin the peculiarity of a few orders that they cannot trace back to a single founding personality. Instead, they originated from crusaders and pilgrims who had settled on Mount Carmel in Palestine during the mid-12th century, initially as hermits, and had joined together in a loose association to live a strictly contemplative life. When they had to flee to Europe in the 13th century because of the increasing Saracen threat, their way of life also changed, and they adopted the lifestyle of the mendicant orders. Their habit is brown and white on holidays.

To the facsimile

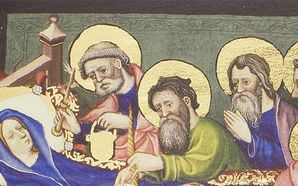

In the 15th century, a female branch was added to the order. Theresa of Avila (1515-1582) then undertook important reform movements with John of the Cross (1542-1591), which not only led to a more radical contemplative orientation more in line with the origins, but also, after her death, to a split into the Carmelites and Discalced Carmelites: the latter still wear no shoes, but sandals as the footwear of the poor and are one of the strictest women's orders in existence. They live completely isolated in the convent, which the nuns cannot actually leave and only doctors and craftsmen can enter. The consultation room with a grid symbolizes this radical turning away from the world.

The Augustinian Hermits

To the facsimile

The last order that belongs to the mendicants are the Augustinian Hermits. From their foundation, however, the relationship to St. Augustine is rather loose: during the 13th century it was more important to find an already recognized rule for the union of several loosely connected groups of hermits because the Council of Lateran IV in 1215 had actually prohibited the founding of new orders.

To the facsimile

Since the Rule of Augustine left many things open, it was well suited to this purpose. The hermitic way of life was also soon no longer an actual characteristic of the order, so that in 1963 the word "hermits" was deleted from the self-designation and the order is still known today as Ordo Sancti Augustini (OSA). The most famous Augustinian hermit in history is probably Martin Luther (1483-1546).

Beguines and Recluses

To the facsimile

A special hybrid between the lives of religious and lay people originated in the Netherlands and found some offshoots in Germany from the 13th century onwards. Mainly a movement by and for women, the so-called Beguines (or - more rarely - with men: Beghards) lived without religious vows and uncloistered, but very often together in a community, the beguinage. There they dedicated themselves to prayer and active philanthropy, also taking on charitable tasks.

Some also chose to live in a hermitage (or a cell), a completely secluded little room from which they could look down on the altar of a church. The most famous saint from a hermitage is certainly Nicholas of Flüe (1417-1487). His example shows how a completely secluded life in the hermitage of the Ranftkapelle and active participation in the political and ecclesiastical environment need not be a contradiction in terms.

The Jesuits

Contemporary scoffers thought that the religious community of the Jesuits, founded by Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556) under the name Societas Iesu (SJ), was not a real order at all: they lacked the religious habit, proper monasteries, and the common Liturgy of the Hours. Indeed, Ignatius did not give these things to his now 500-year-old order, which was his life's work. The largest male order of the Catholic Church has nevertheless influenced developments in church and society in an incomparable way.

To the facsimile

Ignatius founded the order not as work of the Counter-Reformation, but originally wanted to settle down with friends in the Holy Land. But when these plans failed, the friends made themselves directly available to Pope Paul III (hence the additional special promise of obedience to the papcy, which all members of the order make).

To the facsimile

Not only did he actually use the order for the Counter-Reformation, but he also had to reckon with the fact that some members of the order took a particularly critical and at the same time loyal attitude to the Catholic Church: Without Friedrich Spee's objection, the persecution of witches would have taken a different course in Europe; in South America, the so-called Jesuit reductions showed the fruits of the humane treatment of the supposedly savage indigenous population; and the educational system would be completely different for pupils and students without the Jesuits' colleges and order schools, which are still renowned today.

Its influence was often too great for the critics of the order and the Jesuits were accused of elitist arrogance. In fact, the order still attaches great importance to a sound philosophical education, and many members of the order are active in non-theological professions (such as scientific research). Certainly the most famous Jesuit of our time is Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who after his election as pope in 2013 chose the name Francis in honor of St. Francis of Assisi, and not Francis Xaver (1506-1552), a contemporary of Ignatius and founding member of the order.