Carolingian Manuscripts

Initiated by the Emperor Charlemagne (742-814), who created a successor state to the Western Roman Empire, the Carolingian Renaissance (ca. 780 – ca. 900) was the first of three that ultimately culminated in the Italian Renaissance. It is named after Charlemagne, called Karolus by contemporary chroniclers, who not only brought order and stability to Latin Europe, but established monasteries throughout his empire and scriptoria at his court, as well as a culture of art patronage among the Frankish nobility and princes of the church.

His importation of Irish, Anglo-Saxon, and Byzantine scholars – Alcuin of York (ca. 735-804) foremost among them – not only united the greatest contemporary minds, but also created a synthesis of artistic styles. These great minds also created a uniform script for the empire, known as Carolingian miniscule, which is the foundation of our modern fonts.

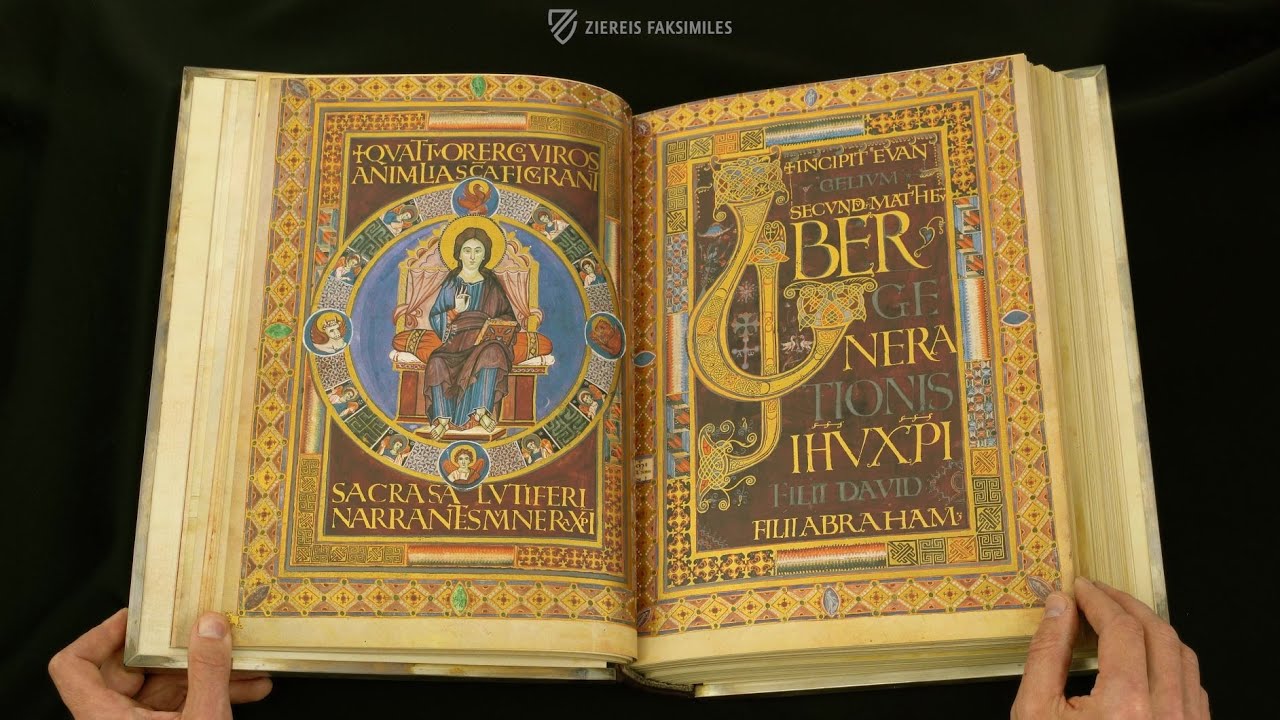

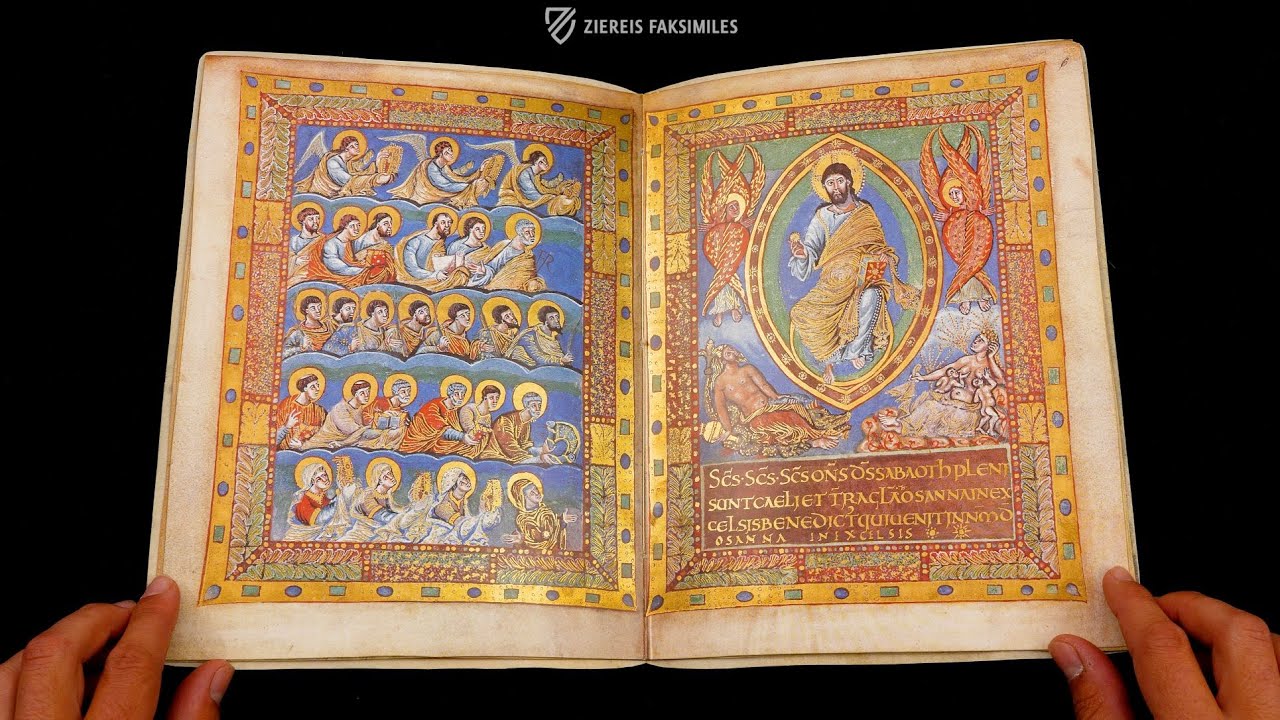

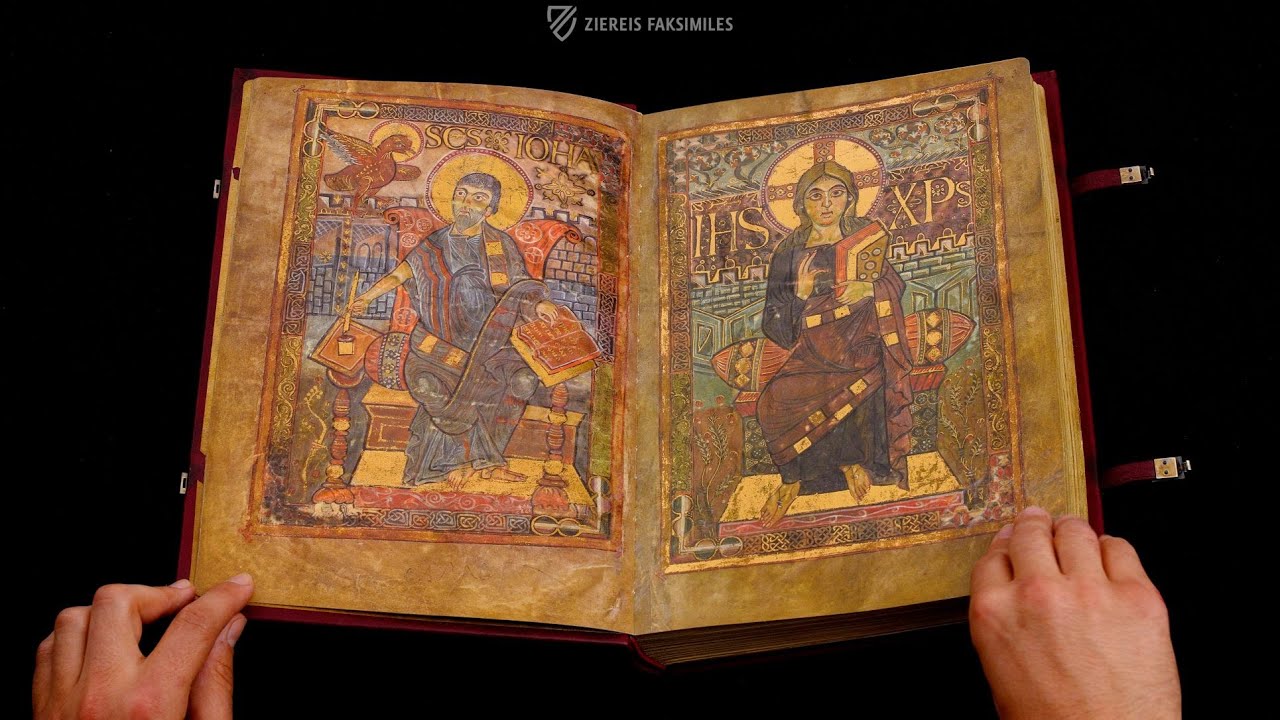

Carolingian illumination first emerged ca. 780 in the Court and Palace Schools of Charlemagne and would last well into the 10th century, producing manuscripts like the Bible of St. Paul Outside the Walls that possess such luxury and sophistication that they are the peer of any other. It is a blend of the dynamism of Insular art with the monumental and iconic aesthetic of Late Antique and Byzantine art, the result was an expression of both continuity with Rome as well as signaling the beginning of a new era. The Ottonian, Romanesque, and Gothic artistic traditions all have their roots in Carolingian art and can therefore be considered to be its descendants.

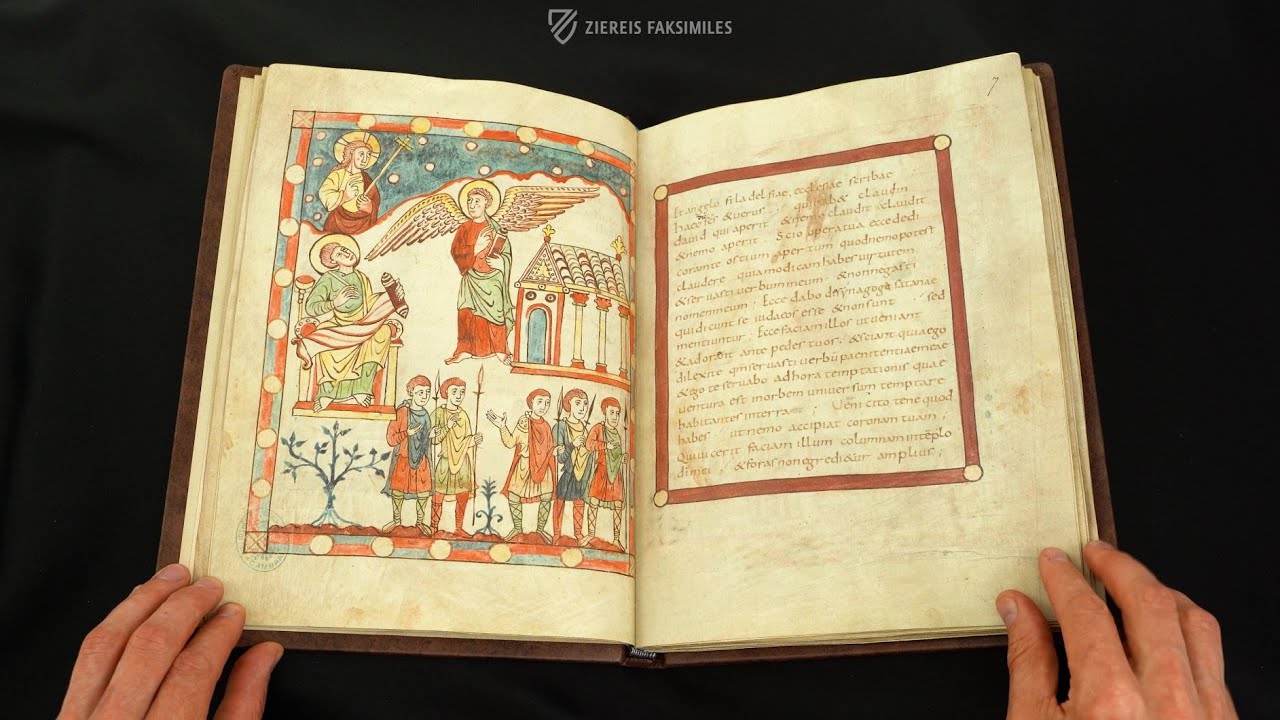

Demonstration of a Sample Page

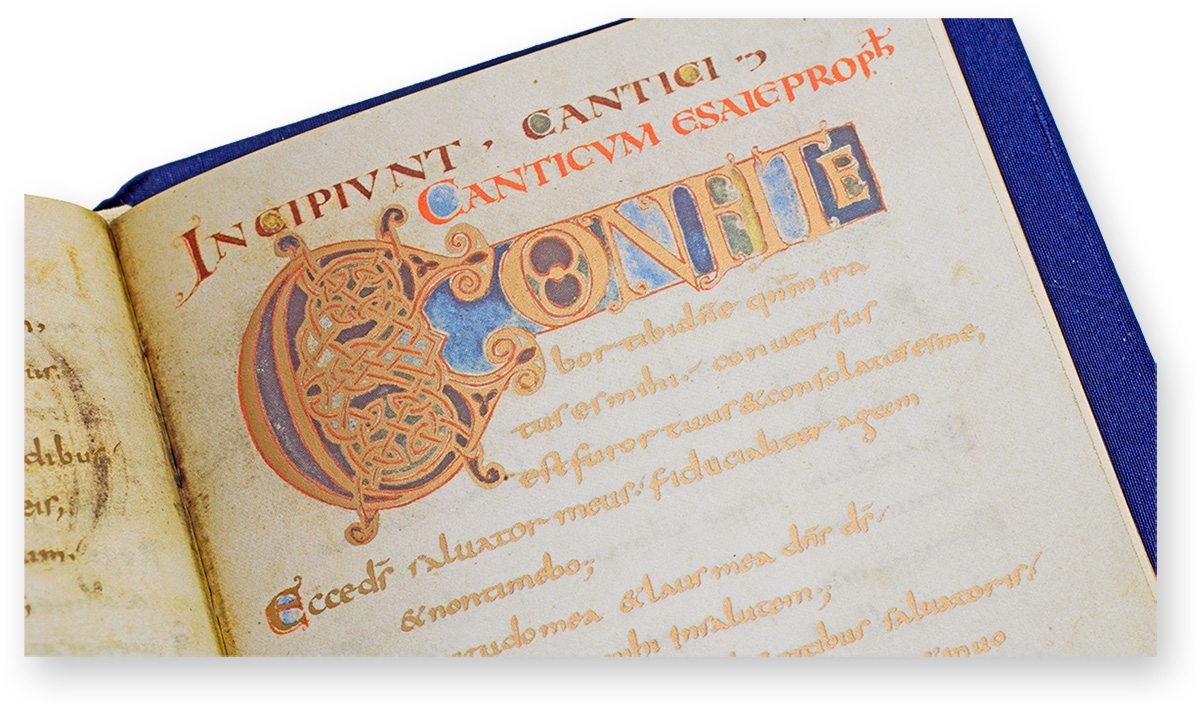

Bible of St. Paul Outside the Walls

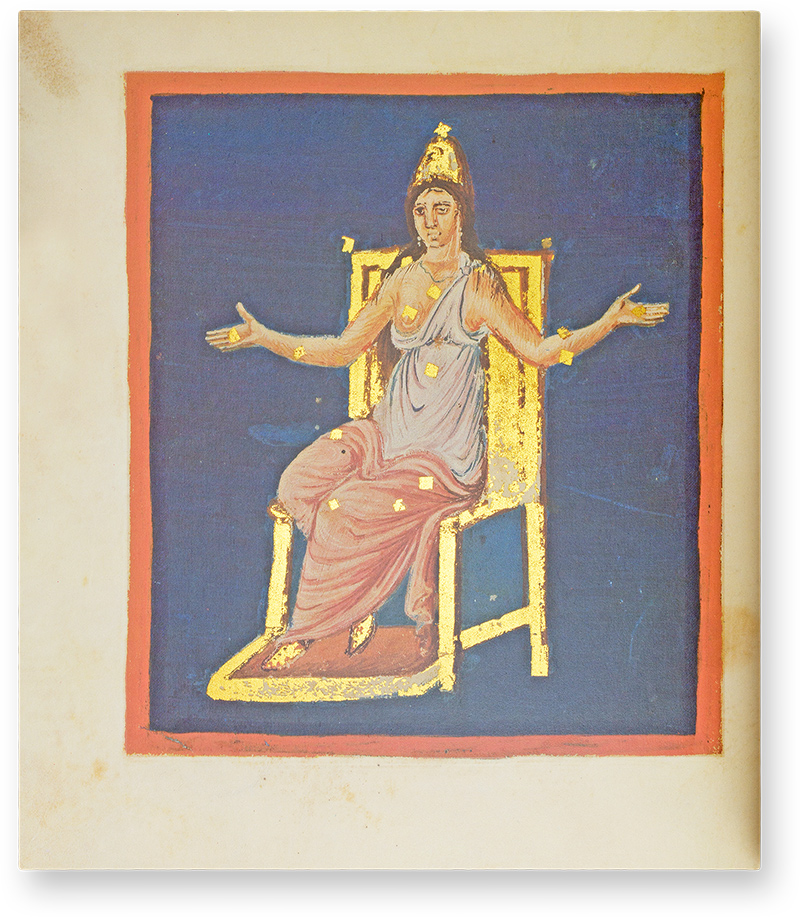

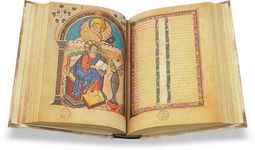

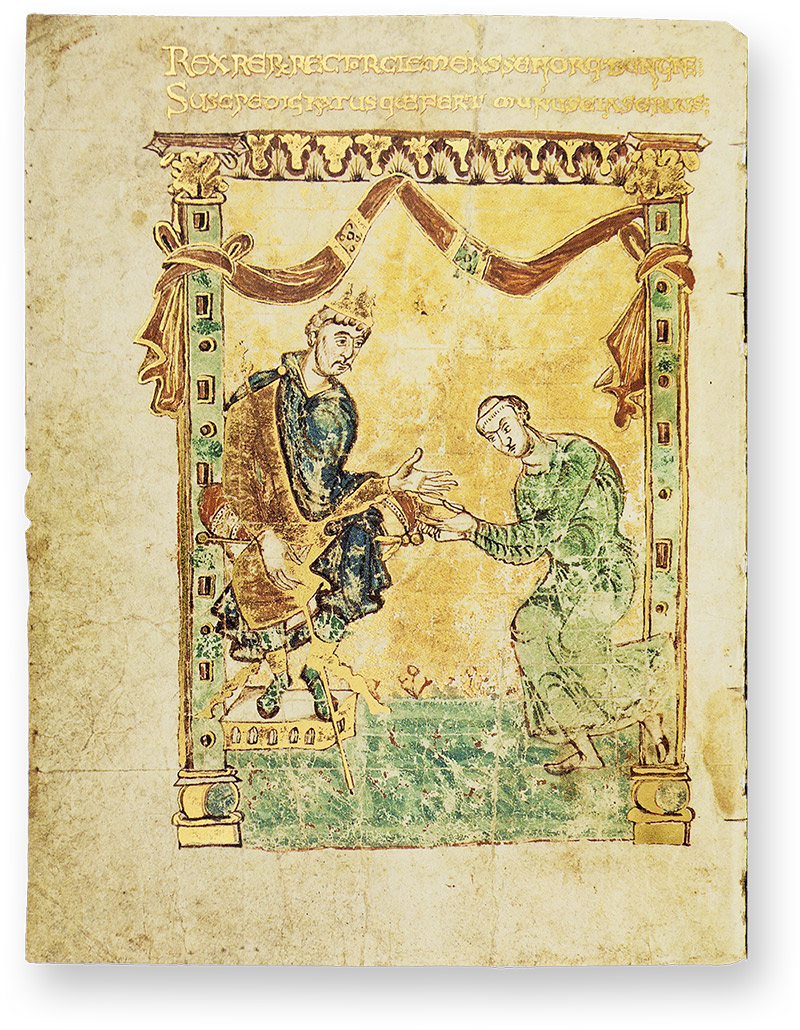

Dedication Portrait of Charles the Bald

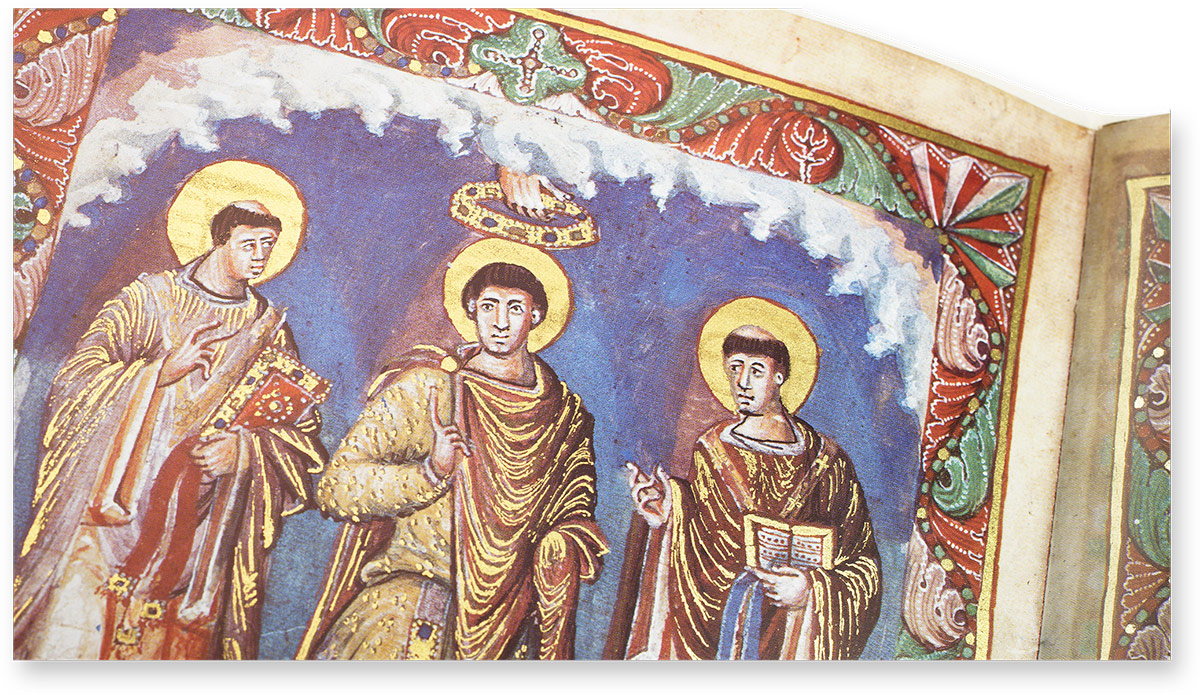

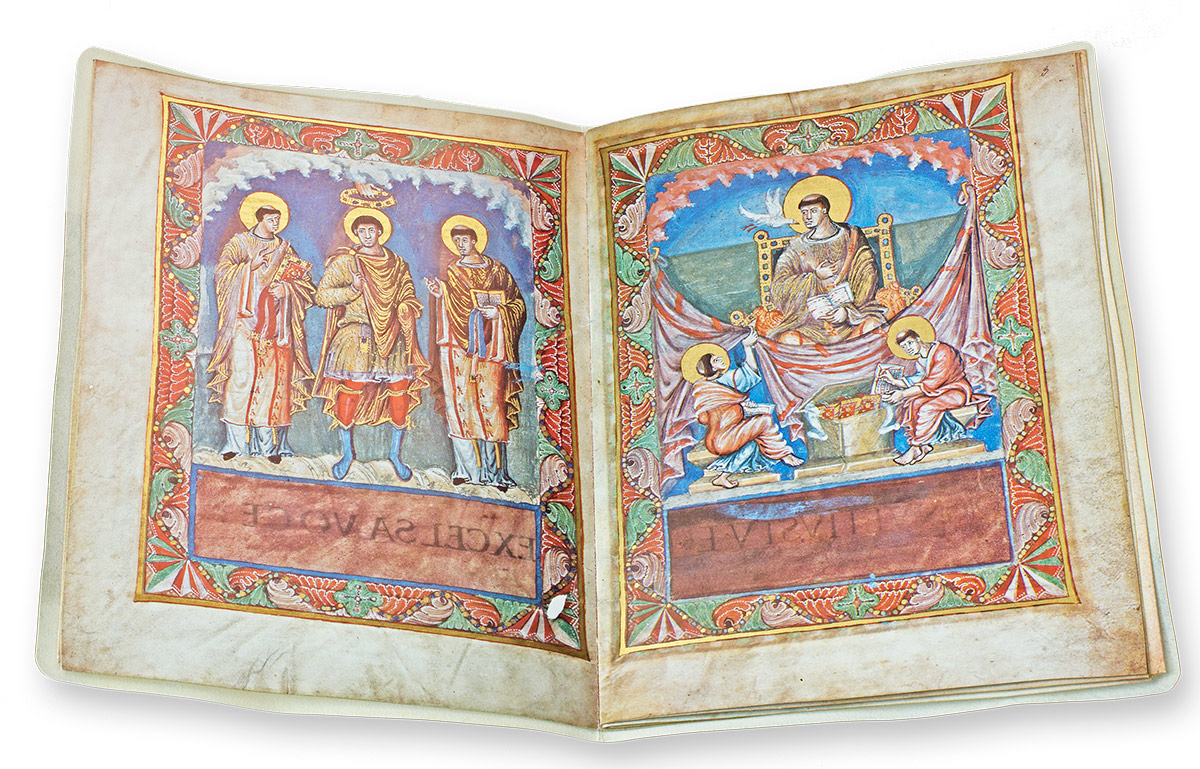

This magnificent full-page miniature depicts Charles the Bald, grandson of Charlemagne, crowned and dressed in a bejeweled toga and a patterned tunic in the manner of a late Roman emperor. He is enthroned within an elaborate classically styled canopy with curtain walls that overlaps the acanthus leaf frame, making appear as though it were sticking out from this border.

Saints and angels with golden halos look down from heaven at Charles flanked by two armed men and two richly dressed ladies of the court. The book itself is absent, which is typical for dedication miniatures from this period. Expensive pigments as well gold and silver leaf were used to create the splendid image and the accompanying text is written in gold ink against a purple-dyed background.

Light Emerging from the Darkness

The so-called Carolingian Renaissance (ca. 780 – ca. 900), during which time numerous monasteries with scriptoria and schools at various royal courts were established, laid the foundations of what most people would think of as the Renaissance, which began in 14th century Italy before spreading north. It was initiated by the Emperor Charlemagne (742-814), whose intent was to establish a successor state to the Western Roman Empire, this not only meant conquering and administering territory but restoring occidental learning.

Although Western Europe in the misnamed Dark Ages was not as devoid of art and culture as one might think – Insular illumination from the 6th to the 8th centuries is some of the finest medieval art to survive to the present – manuscript production increased exponentially under the Carolingians, as did the sophistication of artistry and the refinement of materials.

Although the instability of the 10th century, caused by raids and invasions by Vikings, Arabs, and Magyars ended this first Renaissance, Carolingian art continued to be produced in the 10th century and gradually evolved into other artistic styles. The Carolingian Renaissance and its artistic style were the catalyst for the high-medieval resurgence of European art and learning that eventually led to the Italian Renaissance.

Experience more

The Carolingian Dynasty

First founded by Charles Martel (ca. 688-741), victor of the Battle of Tours (732), and elevated to unparalleled glory by Charlemagne, who was often referred to as Karolus in contemporary accounts, the Carolingians were one of the most powerful and important European dynasties. Charlemagne’s empire encompassed modern-day France, the Low Countries, Germany, Northern Italy, and had vassal states in central Europe.

He was also one of the greatest patrons of art and education in history, as were his descendants. The Carolingians consciously adopted an artistic style that imitated the art of Late Antiquity because they were claiming to be the heirs of the Romans. This is why figures are portrayed in togas instead of reflecting contemporary fashions, for example.

To the facsimile

This focus on establishing themselves as the inheritors of classical traditions has created a debate among historians, arguing that it was the rise of the Carolingian Empire, and not the destruction of the Western Roman Empire, that actually marks the beginning of the Middle Ages. This contested thesis claims, based upon the contemporary artistic aesthetic, that what is traditionally thought of as the Early Middle Ages is in fact part of Late Antiquity. Nonetheless, this artistic style was a statement by the Carolingian dynasty: we are the new Caesars.

Carolingian Miniscule: Standardization and Legibility

Although learning did not cease in the centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, monasteries became isolated islands of learning. This resulted in the de-evolution of the uniform script of the Romans into a galaxy of fonts ranging from awfully sloppy to terribly intricate, most of which were illegible to people from outside the community that produced them.

Due to their remoteness and relative tranquility, monasteries in the British Isles, Ireland in particular, did not suffer this fate and would play a key role in establishing a uniform script that would be legible to all learned people. Before Charlemagne could unify the scholarly community of the West, he would first need to do something about this Balkanization of fonts.

Thus, Charlemagne imported Anglo-Saxon and Irish monks like Alcuin of York (ca. 735-804) to his new capital at Aachen to standardize script, take charge of scriptoria, and restore standards that scholars had previously enjoyed and which we take completely for granted today. Carolingian miniscule is characterized by its clear, uniform, round shapes that are a combination of Roman half uncial and insular scripts.

Carolingian miniscule originated ca. 800 and was used until its decline in the 12th century, but then experienced a revival during the Renaissance by scribes who used it as the basis for new fonts. This script was critical for creating legible copies of ancient texts because most of our modern knowledge of classical literature is grounded in translations from Charlemagne’s scriptoria. Therefore, the invention of Carolingian miniscule is second to none among the cultural contributions made by the “Father of Europe”.

Experience more

Influences and Aesthetics

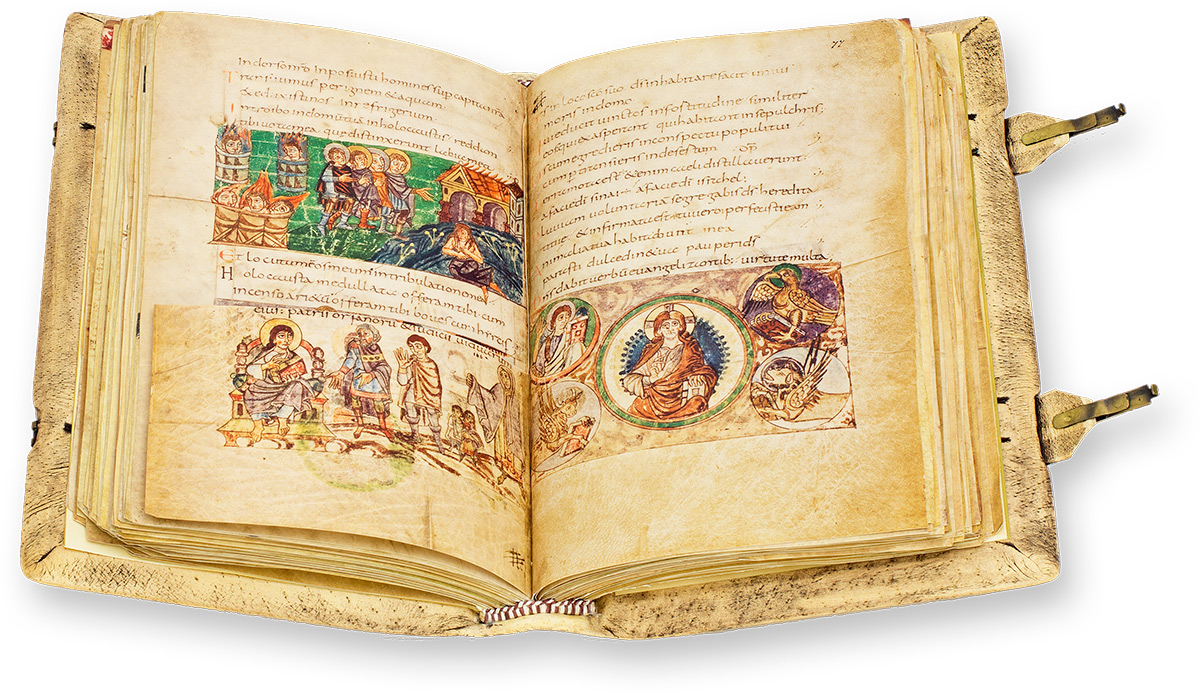

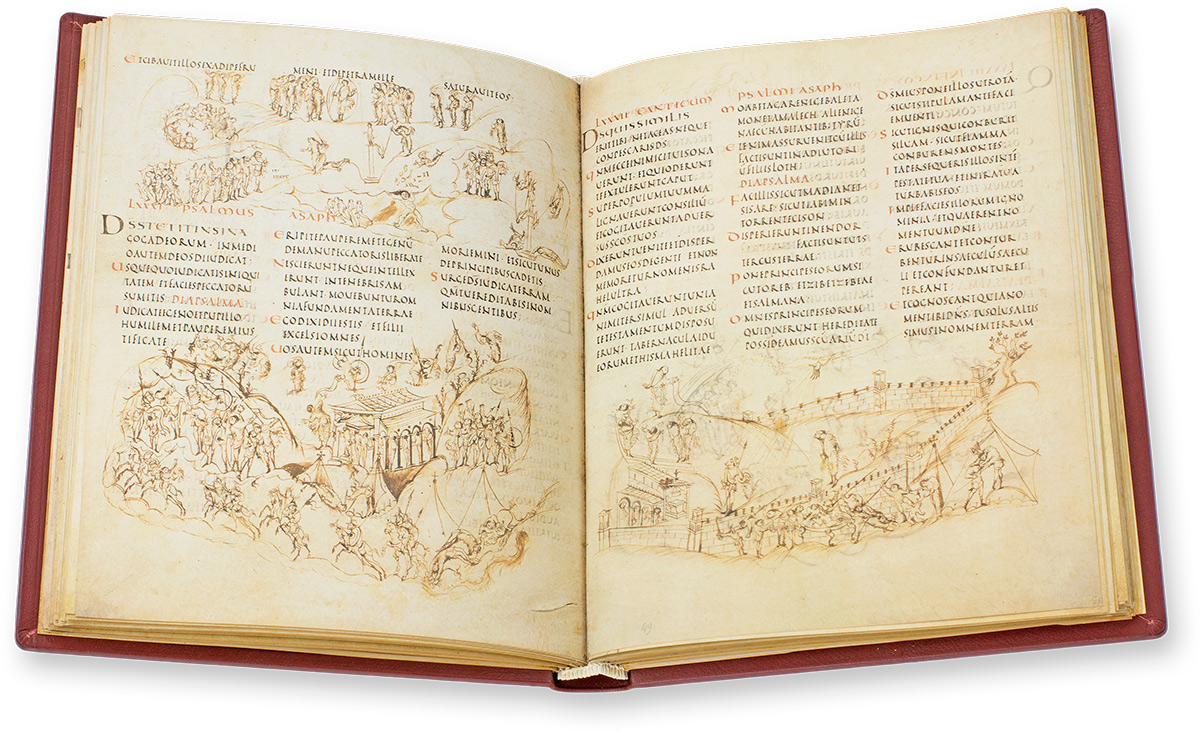

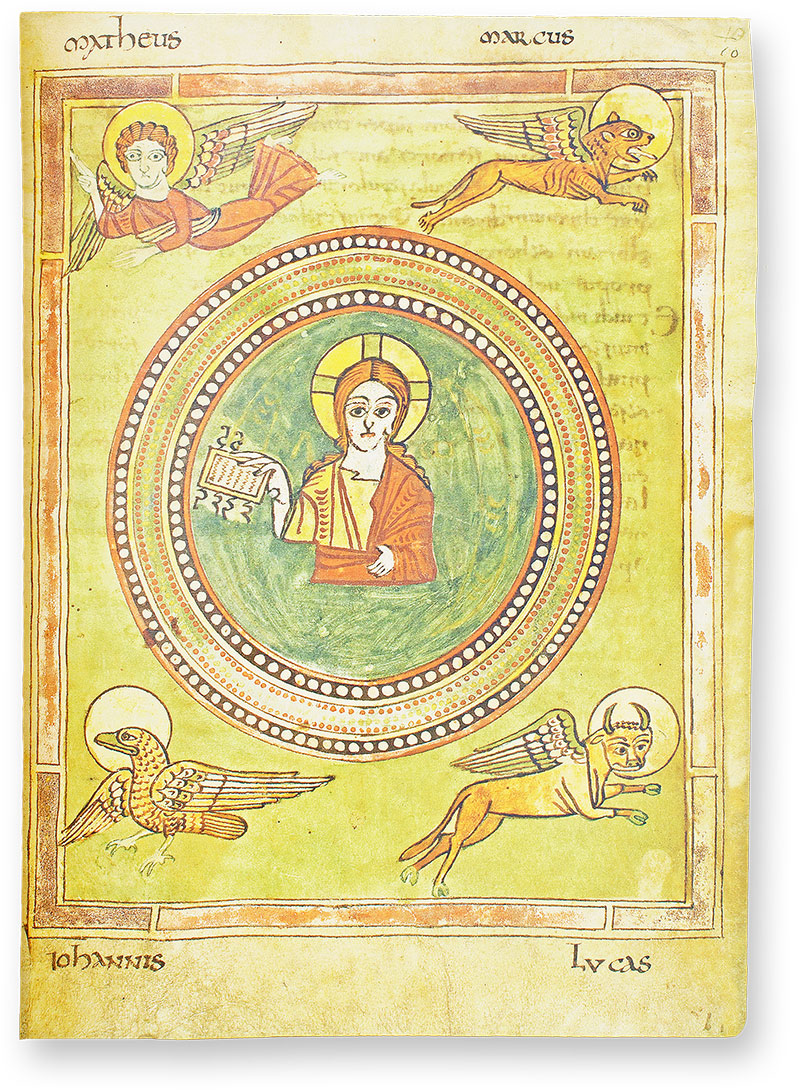

Carolingian illumination is characterized by the distinct blending of northern and eastern illumination styles, specifically those of the illuminators of Byzantium and the British Isles, and the result of the importation of illuminators and scribes trained in those traditions.

To the facsimile

Although strongly rooted in classical art, Byzantine illumination abandoned realism in favor of an abstract or anti-naturalistic character of great symbolic power and was representative of the connection between religion and imperial power in the Byzantine Empire. As a result, it often has monumental figures set against monochromatic or architectural backgrounds.

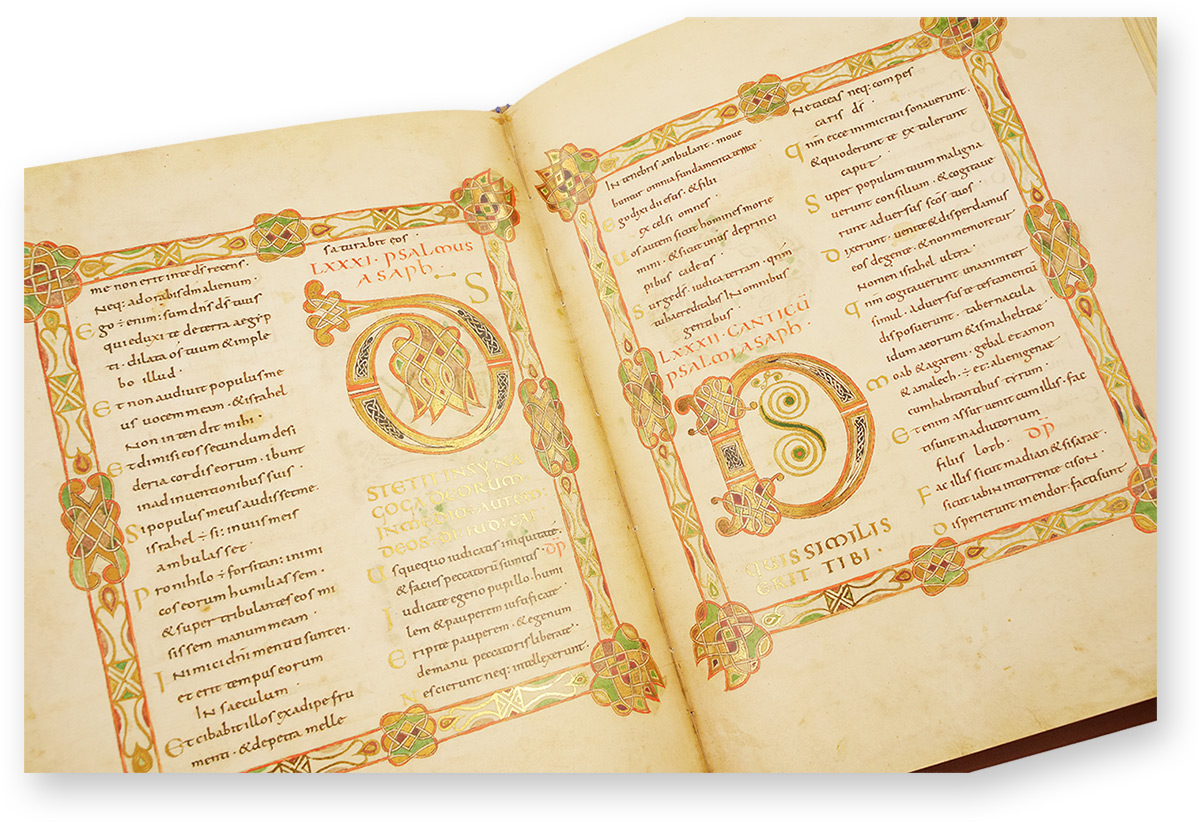

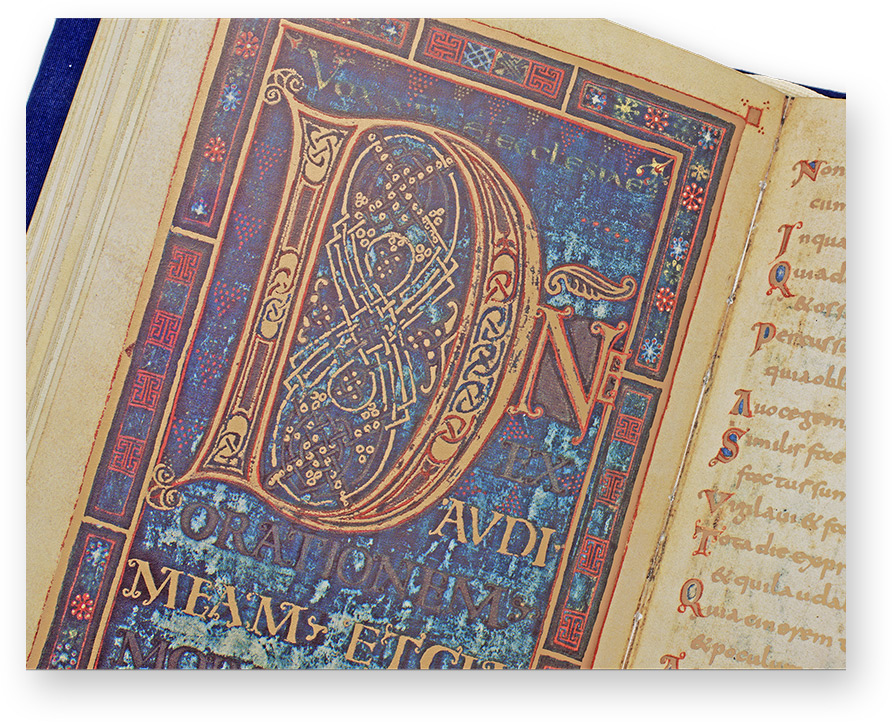

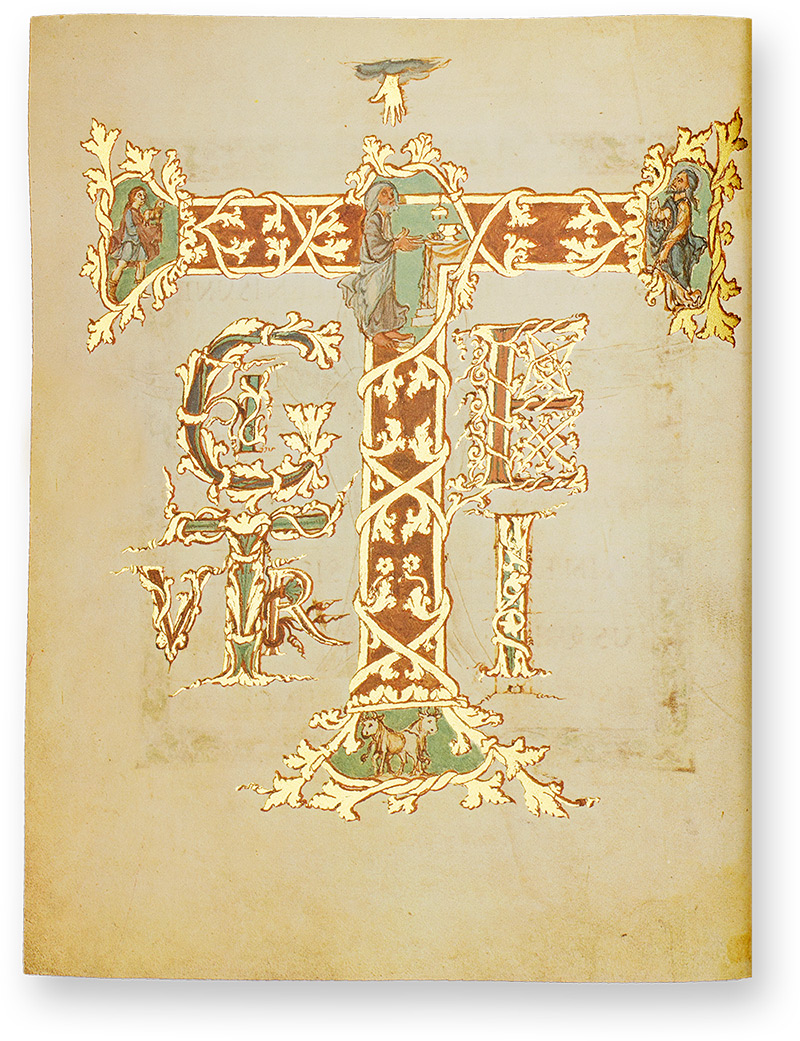

Insular or Hiberno-Saxon illumination has its origins in pagan Celtic and Germanic religious traditions, but also has influences in Roman and Coptic art, particularly with regard to its depictions of carpets and mosaics. Insular art is most clearly characterized by its intricate interlace; these patterns, sometimes called Celtic knots, often formed frames for images such as portraits of the Evangelists and were used to create incredibly artful and complex initials both great and small.

Carolingian art would combine these styles in an aesthetic balancing the chaotic energy of the Insular style with Byzantine solemnity, an aesthetic for an emperor who was looking to the past while also establishing a new dynasty.

Experience more

Patrons and Centers of Production

To the facsimile

Aside from Charlemagne, other high-ranking members of the Frankish nobility, including both his legitimate and illegitimate descendants, also patronized splendidly illuminated manuscripts. These patrons would often be portrayed in “dedication pictures” within the manuscript, or they would have the intended recipient depicted as though they were being presented the manuscript.

Such splendid manuscripts could either be commissions for personal use or could be intended for ceremonial purposes and were given as gifts to monasteries or cathedrals, sometimes part of a larger endowment. These were usually made by cleric-artists (who were almost always anonymous) who worked at one of the scriptoria established by Charlemagne at his royal court or in monasteries founded by him.

The center of Carolingian illumination shifted over the decades, as did the dominant style. The “Court-” and “Palace School” of Charlemagne (also called the Ada School) at Aachen were the first centers of artistic production. Operating contemporarily, the former was led by Alcuin and mostly consisted of Irish and Anglo-Saxons while the latter seems to have been staffed by artists from Byzantium or Byzantine Italy. Rheims, Tours, and Metz would later emerge as centers of manuscript production, most of them patronized by his descendants, and each with its own stylistic markers.

To the facsimile

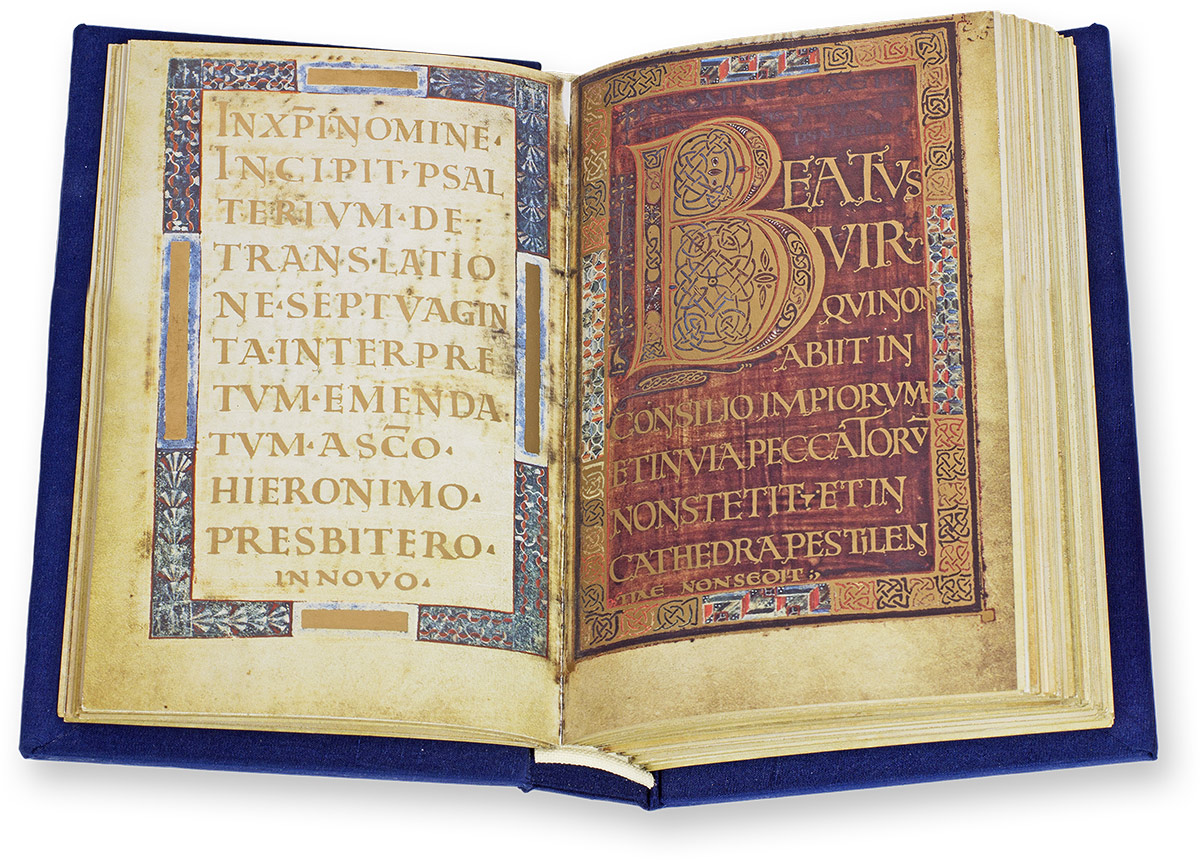

Popularity of the Psalter

Although the book of hours is the most prevalent kind of medieval manuscript in existence today, they did not yet exist in the 8th and 9th centuries, and are descended from the Psalter, a codex containing some or all of the Psalms as well as other devotional texts such as a liturgical calendar and a litany of the saints. Like books of hours, these codices ranged in size from larger texts to be kept in a personal chapel or library to smaller ones designed to be carried on one’s person throughout the day.

To the facsimile

An early example of this is the Golden Psalter of Charlemagne (ca. 795), which was gifted to his wife Hildegard: it is small enough to be carried on one’s person and its rich decoration is characterized by large, detailed historiated initials with bright colors and gold leaf, and a text written entirely in gold ink, but without miniatures.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

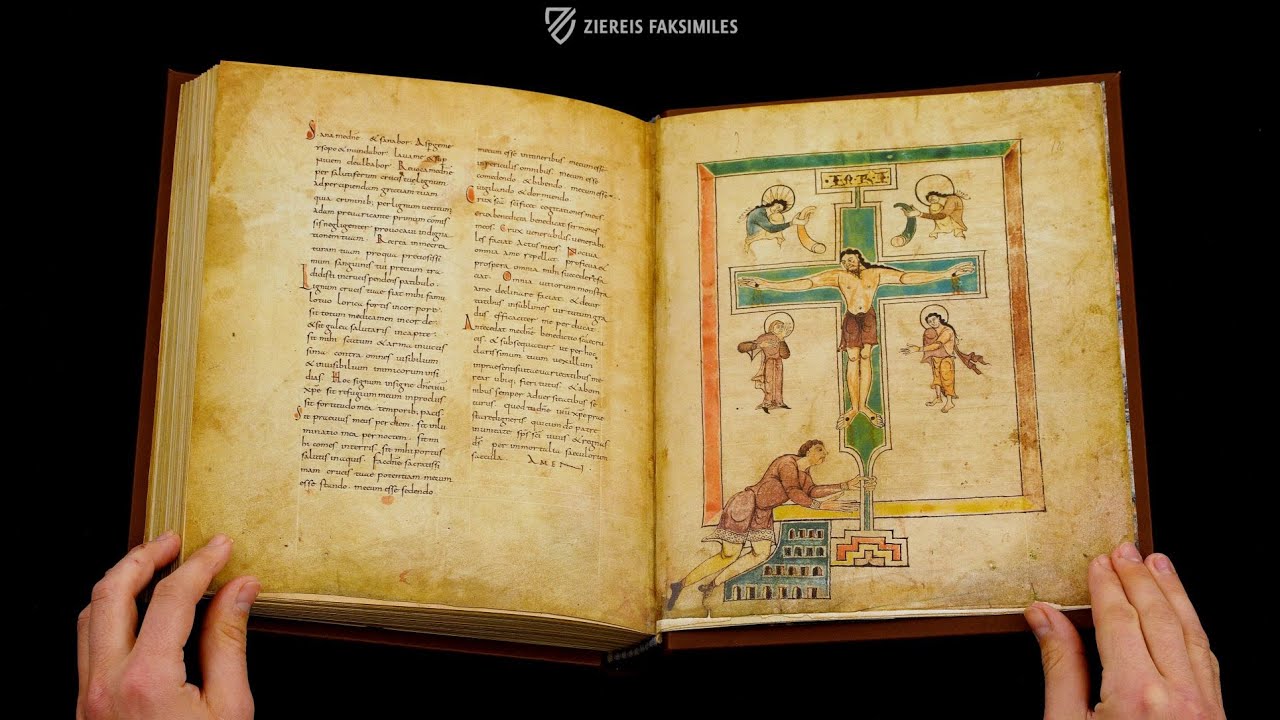

The Stuttgart Psalter and Utrecht Psalter on the other hand, are extensively illustrated with narrative scenes throughout – the illustrations of the former are brightly colored, more classically styled, and some are in fact based on ancient templates, while the masterful pen drawings of the latter are completely unique and resemble the sketches of a great Renaissance master.

To the facsimile

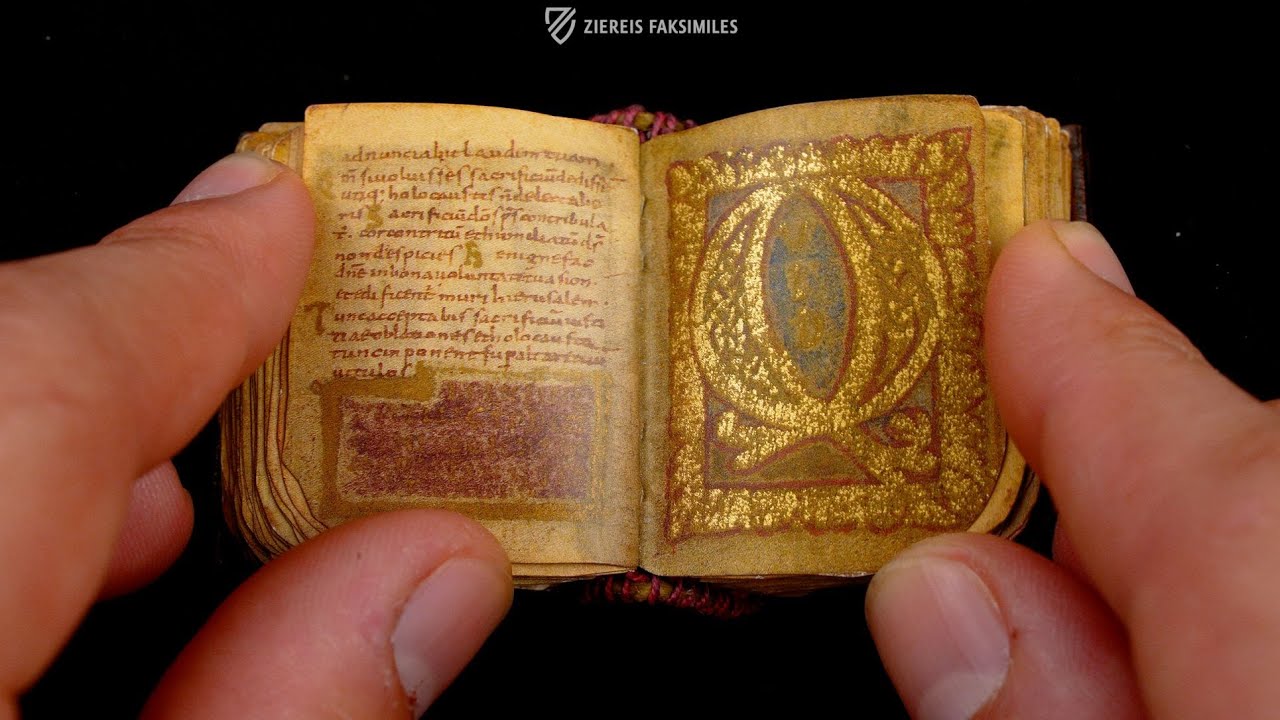

Both point to the skill and diversity of artists in the first half of the 9th century, but the late-9th century Psalterium Sancti Ruperti also testifies to their innovation: it is the smallest medieval manuscript in existence – measuring only 3.7 x 3.1 cm. In spite of being the size of a matchbox, its text is incredibly legible and is adorned by full-page miniatures and initials featuring gold leaf and purple backgrounds.

Experience more

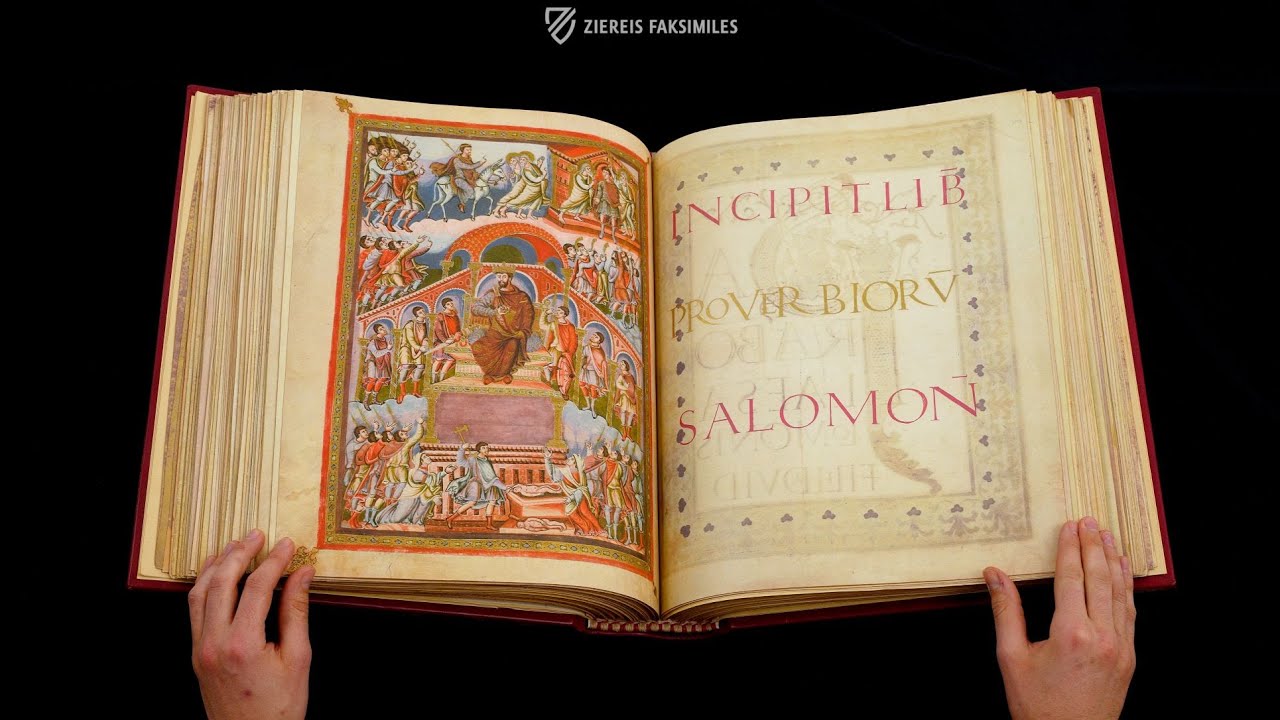

Charlemagne’s Grand Gospel Books

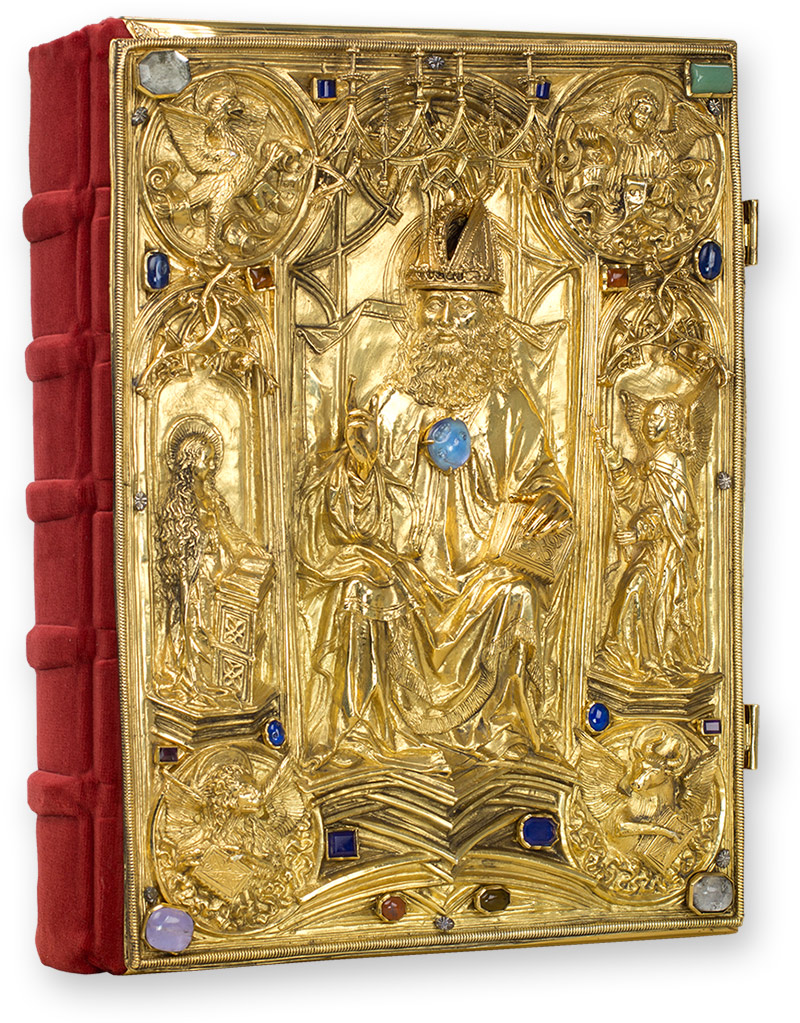

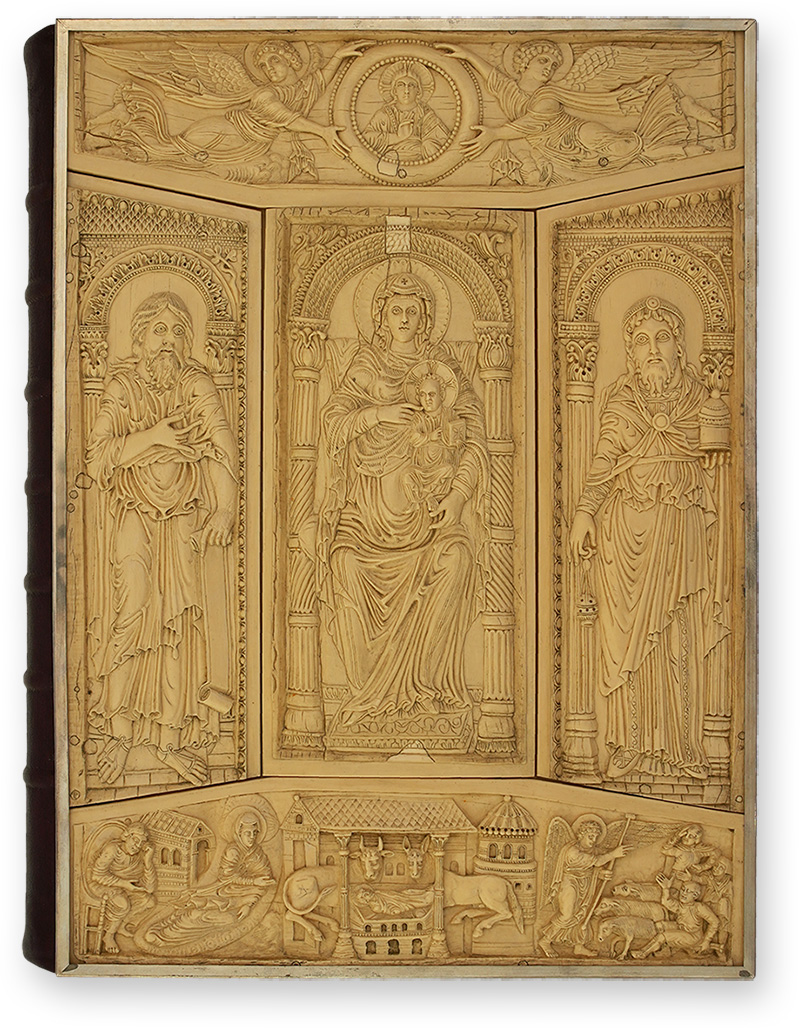

Among the manuscripts commissioned by Charlemagne, there are two massive gospel books which truly stand out and are ranked among the greatest works of medieval European art: the Lorsch Gospels and the Coronation Gospels of the Holy Roman Empire.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

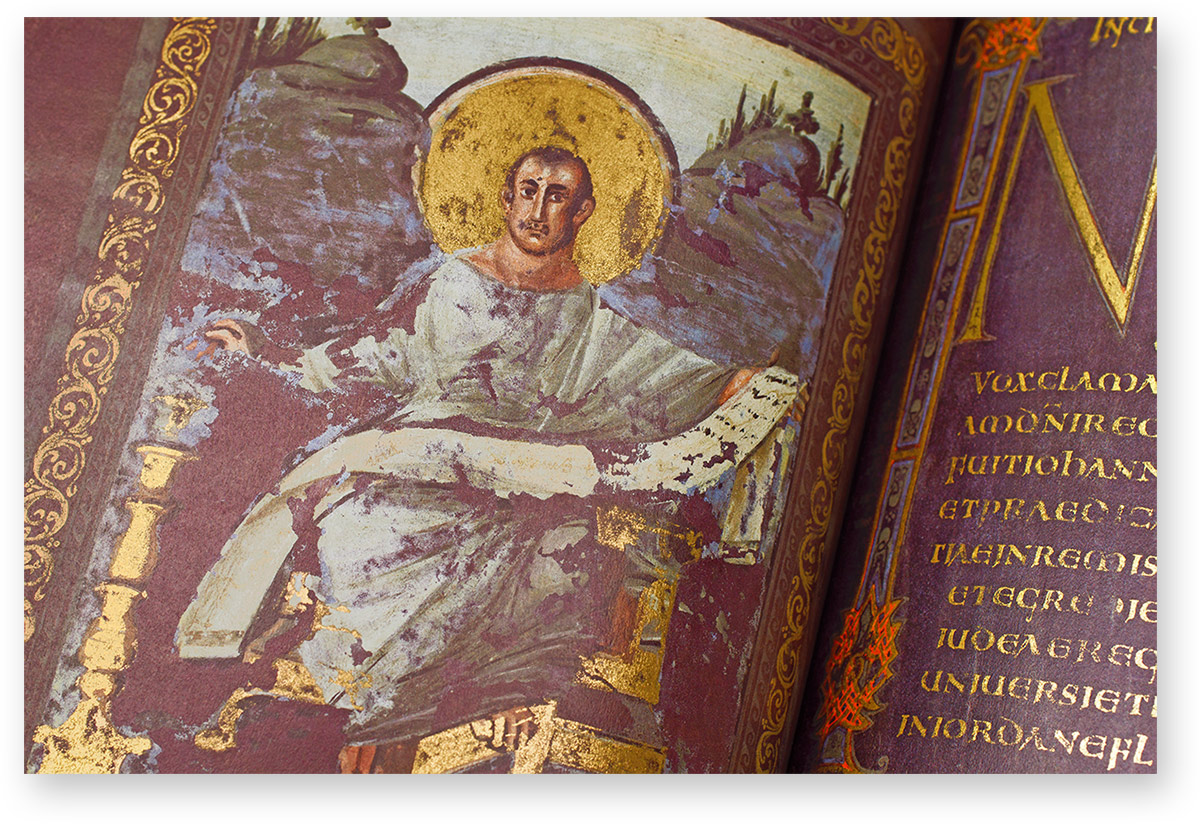

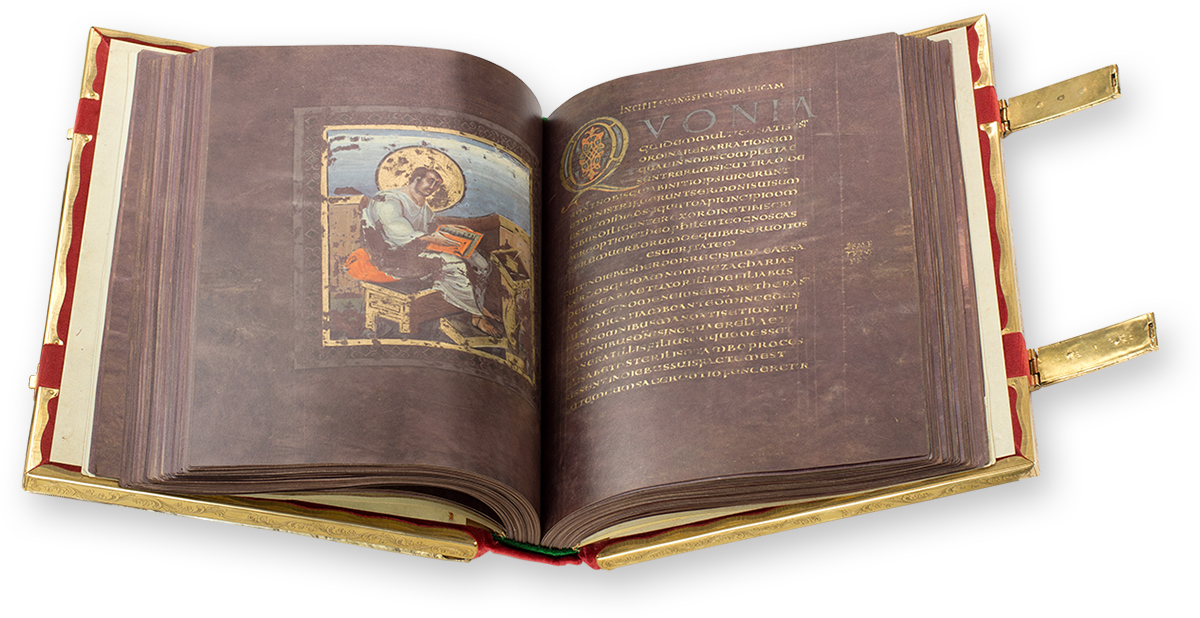

The latter, also known as the Vienna Coronation Gospels for its modern repository, is the codex upon which German kings and emperors swore their oaths of office since (according to legend) it was removed from Charlemagne’s tomb in the year 1000. Originating from shortly before Charlemagne’s imperial coronation on Christmas Day in the year 800, it possesses a truly imperial air thanks to the creations of its presumably Byzantine artists: it consists entirely of purple-dyed parchment pages with biblical texts written in gold and silver ink, large historiated initials, and full-page portraits of the Evangelists.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

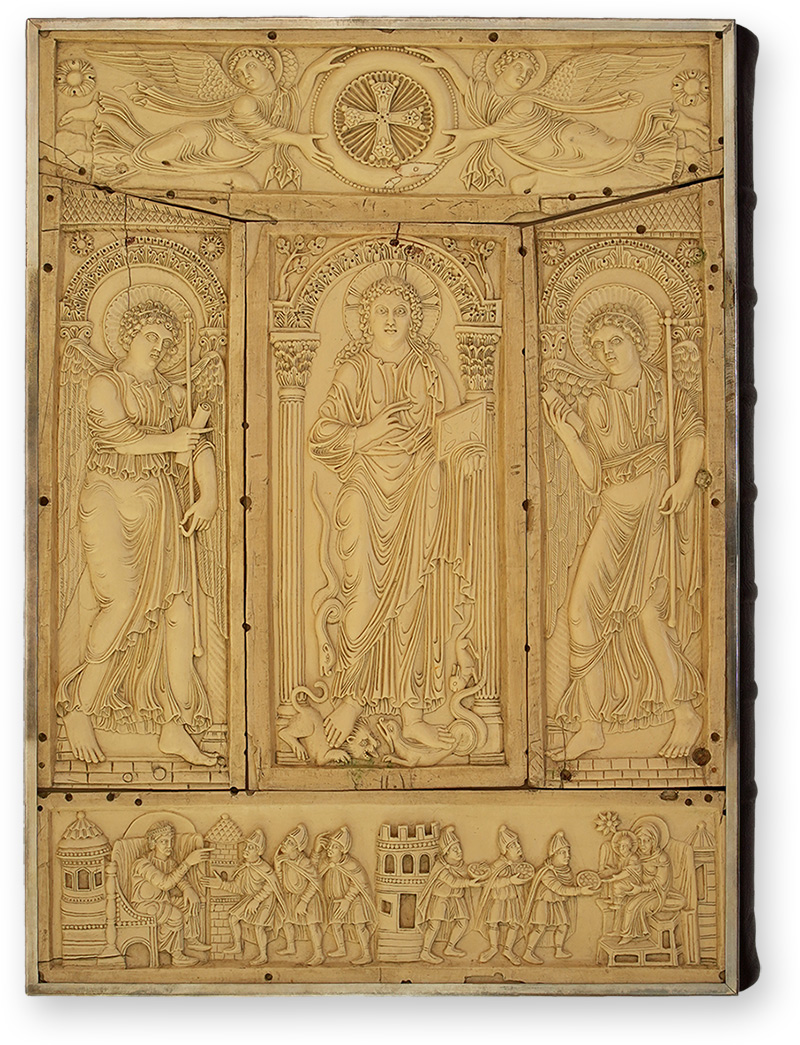

The Lorsch Gospels is also written entirely in gold ink and features some purple pages, has its original covers with ivory reliefs front and back, and was one of the last manuscripts commissioned by Charlemagne to be completed in his lifetime. It was the prized possession of Lorsch Monastery from the 9th century to its dissolution in 1556, and features illumination to rival any other work.

Gleaming Sacramentary Manuscripts

To the facsimile

Two sacramentary manuscripts, texts which contain the readings for priest officiating mass, of great historical and art historical importance originated during the reign of Charles the Bald (823-877), the grandson of Charlemagne. Bishop Drogo (801-855) was a powerful prince of the church, one of the greatest art patrons of the 9th century, and one of Charlemagne’s illegitimate sons.

The Drogo Sacramentary distinguishes itself through its Insular-style initials, ranging from small but detailed initials to large, elaborate ones containing figural scenes relevant to the adjoining texts. This manuscript is the product of one of the court schools and is of a highly personalized nature, e.g. it only contains readings for feast days that the Bishop would preside over.

Only a fragment of the Sacramentary of Metz exists today, and while it is debated whether it is truly a fragment or simply an unfinished work, its illumination is considered some of the finest from the Carolingian epoch. It may have been intended as a coronation manuscript for Charles the Bald himself, as indicated by a coronation picture depicting him being crowned with the hand of God – the only unambiguous expression in Carolingian art of the idea that the sovereign is God’s representative on Earth.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The text is either written in gold or varies between gold, green, and red ink. It has full-page miniature pages filled with small details like acanthus leaves, colored pearl bands, precious stones, rosettes of blossoms, and palmettes in the frames as well as historiated initials with an overwhelming blend of gold and bright, luminous colors. Both are true masterpieces.

Experience more

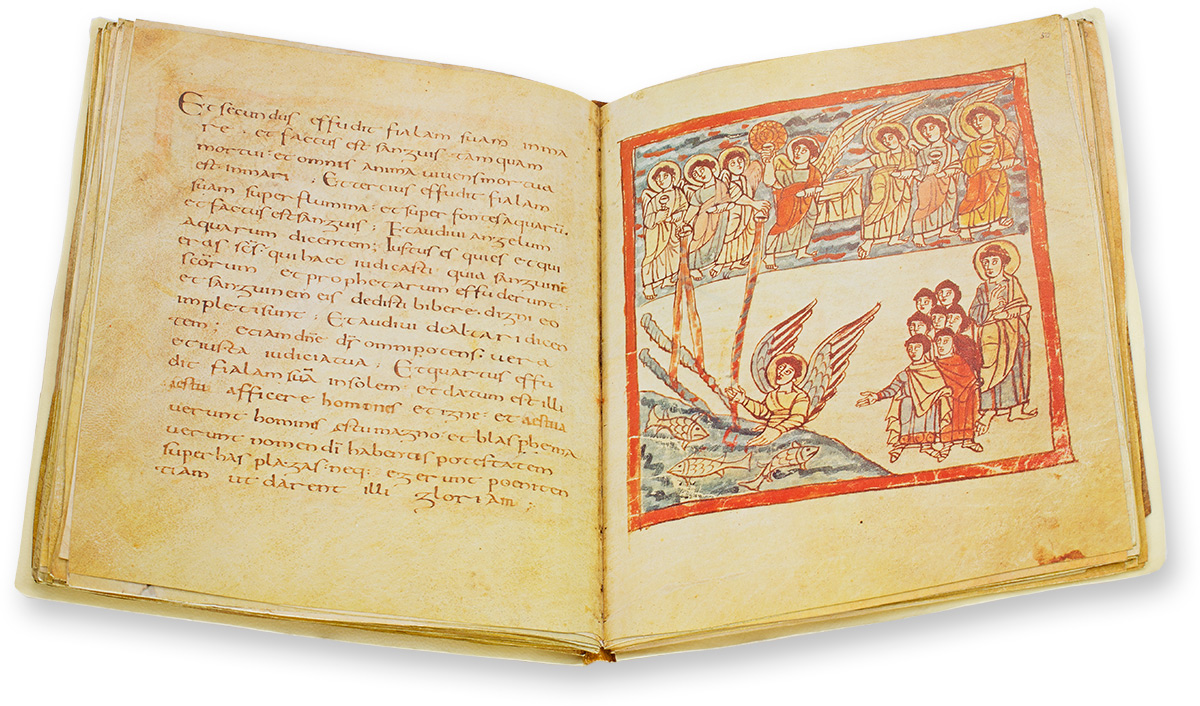

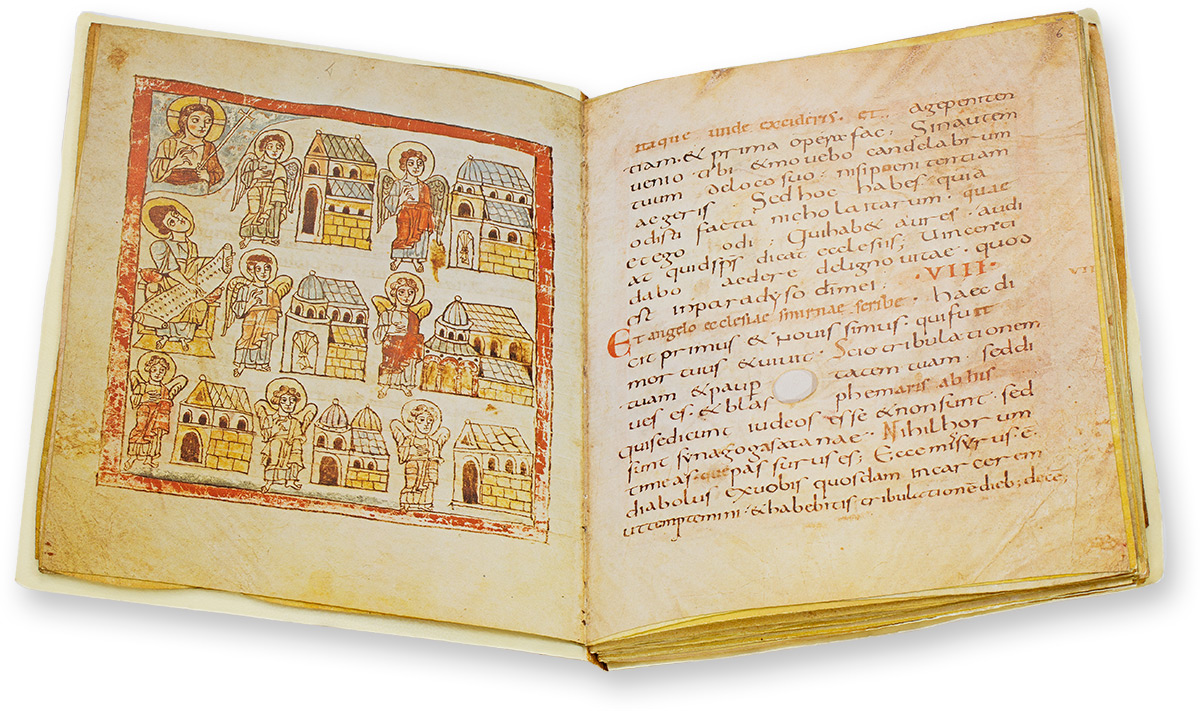

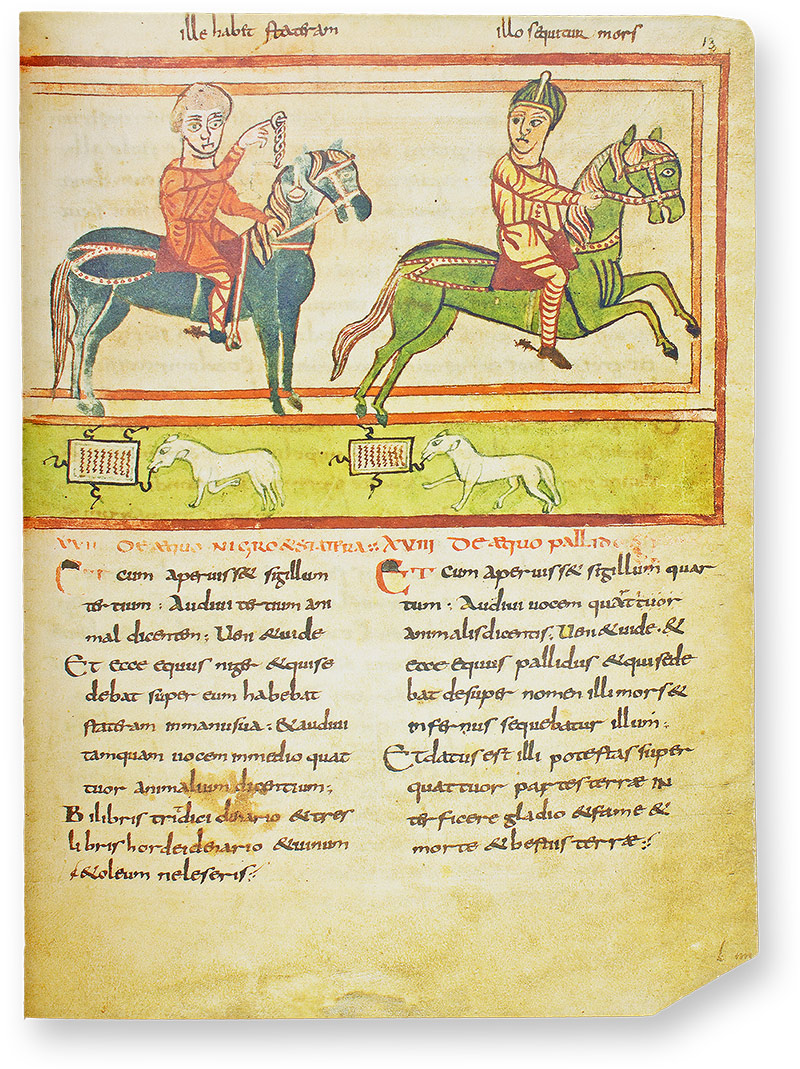

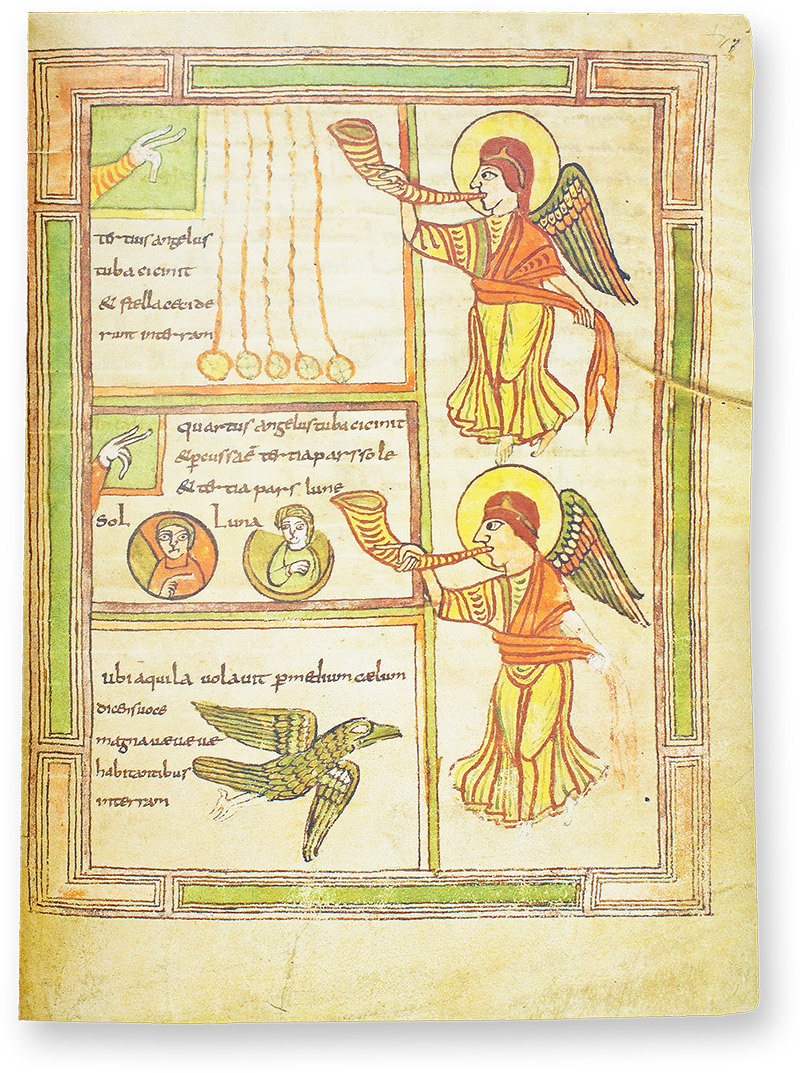

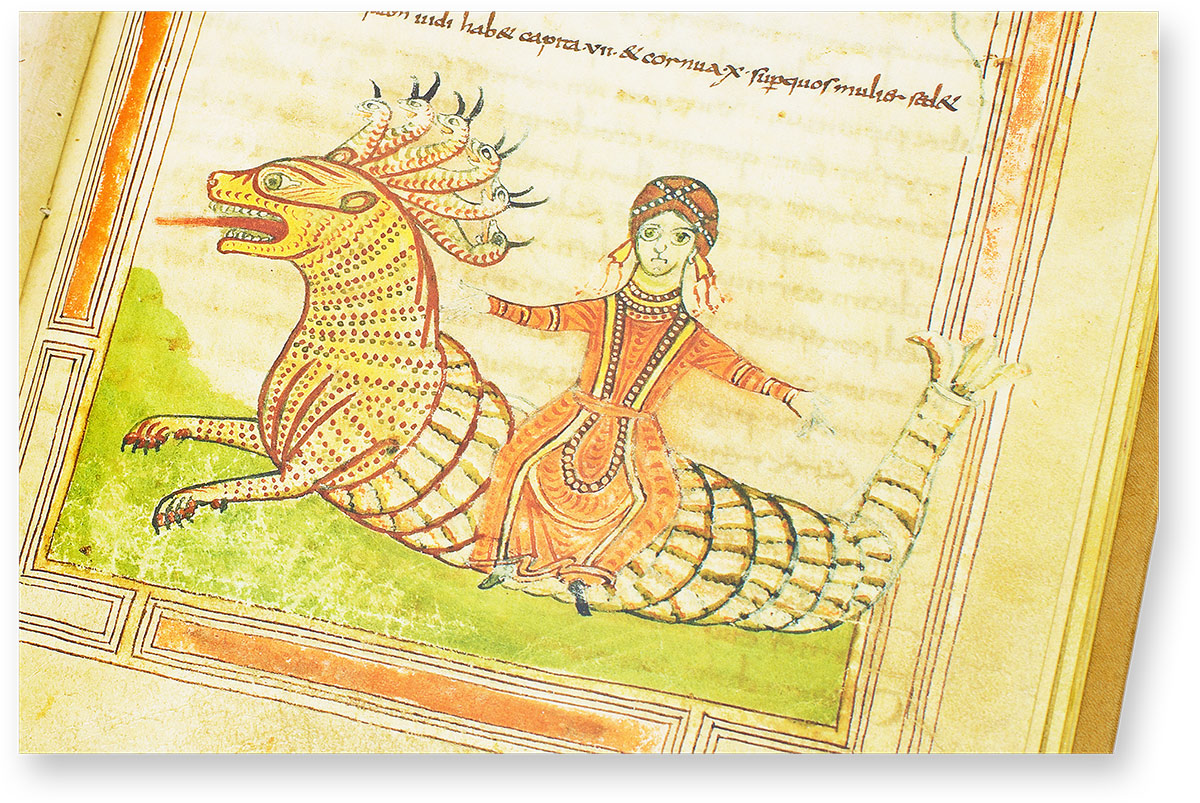

The Carolingian Apocalypse

The ever-popular genre of Apocalypse manuscripts, based on the Book of Revelation, also found expression during the Carolingian Renaissance in the Treves Apocalypse, Apocalypse of Valenciennes, and Cambrai Apocalypse.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

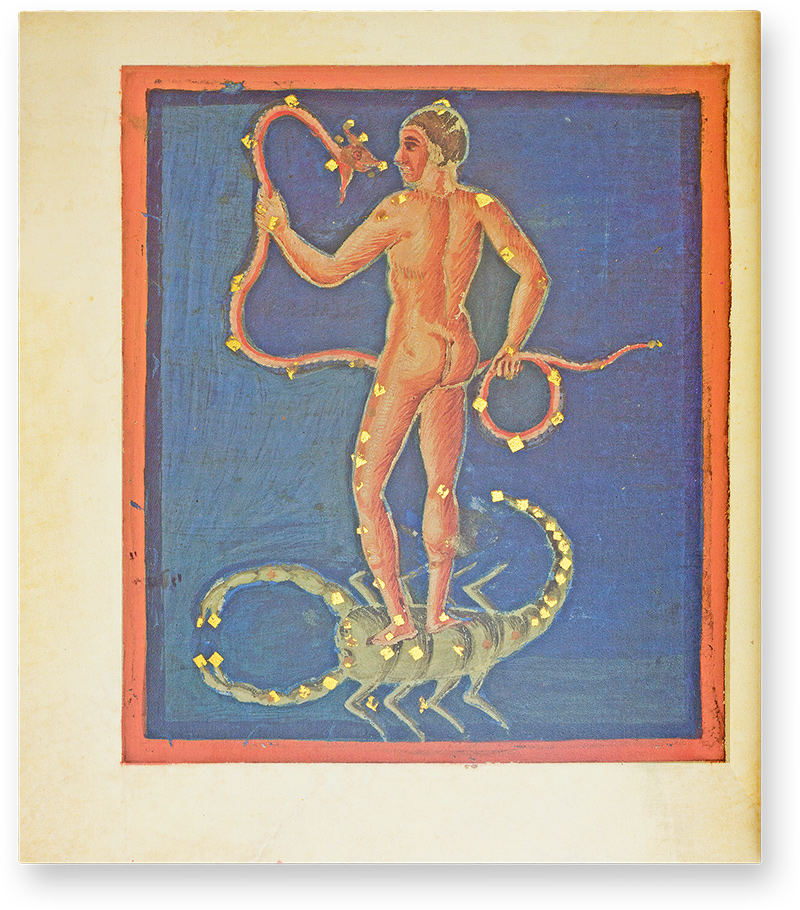

The Treves Apocalypse from ca. 800 is the first illustrated codex of the Revelation of St. John and also the most comprehensive. Its motifs are obvious nods to classical/pagan gods and motifs from the Greco-Roman world.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Meanwhile, the illustration style of the famous manuscripts of the Apocalypse commentary by Saint Beatus of Liébana have their roots in the masterful Apocalypse of Valenciennes, originating in the first quarter of the 9th century. This manuscript is thus of tremendous importance for the history of Spanish manuscript production.

To the facsimile

Finally, the late 9th century Cambrai Apocalypse, probably originating from Cambrai in northern France, stands out from the rest because of its combination of stripped, clear imagery and an intense color palette. Its composition is a stylistic blend of Frankish influences with those of Late Antiquity and its harmonious miniatures are staged by temple architectures and palmettes.

Just as Apocalypse manuscripts in general are some of the most diverse, even this collection of manuscripts, all made within a century of one another in the Frankish heartland of modern-day northeastern France, are incredibly diverse and wonderful in their own ways.

Experience more

Texts on Medicine and the Stars

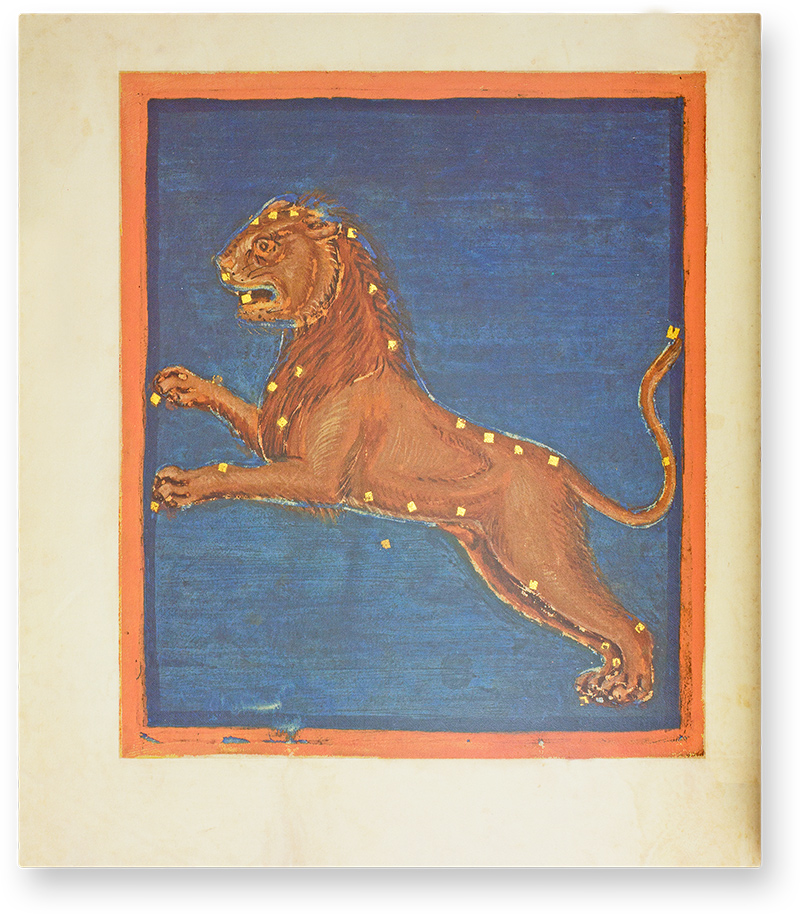

Although religious texts were most often chosen for elaborately illuminated manuscripts, there were also important secular texts preserved in splendid codices on subjects such as medicine and astronomy/astrology.

Charlemagne commissioned a team of monks with the creation of the Herbolarium et Materia Medica, a medical/botanical work with descriptions of a wide range of plants as well as animals. Charlemagne induced the monks of his empire to concern themselves with the applications and cultivation of medicinal plants, and the Carolingian monks also described their experiences in animal husbandry and the biological characteristics of the animals, which had been heretofore unexplored, all of which they recorded with detailed illustrations. This is the oldest known manuscript of its type.

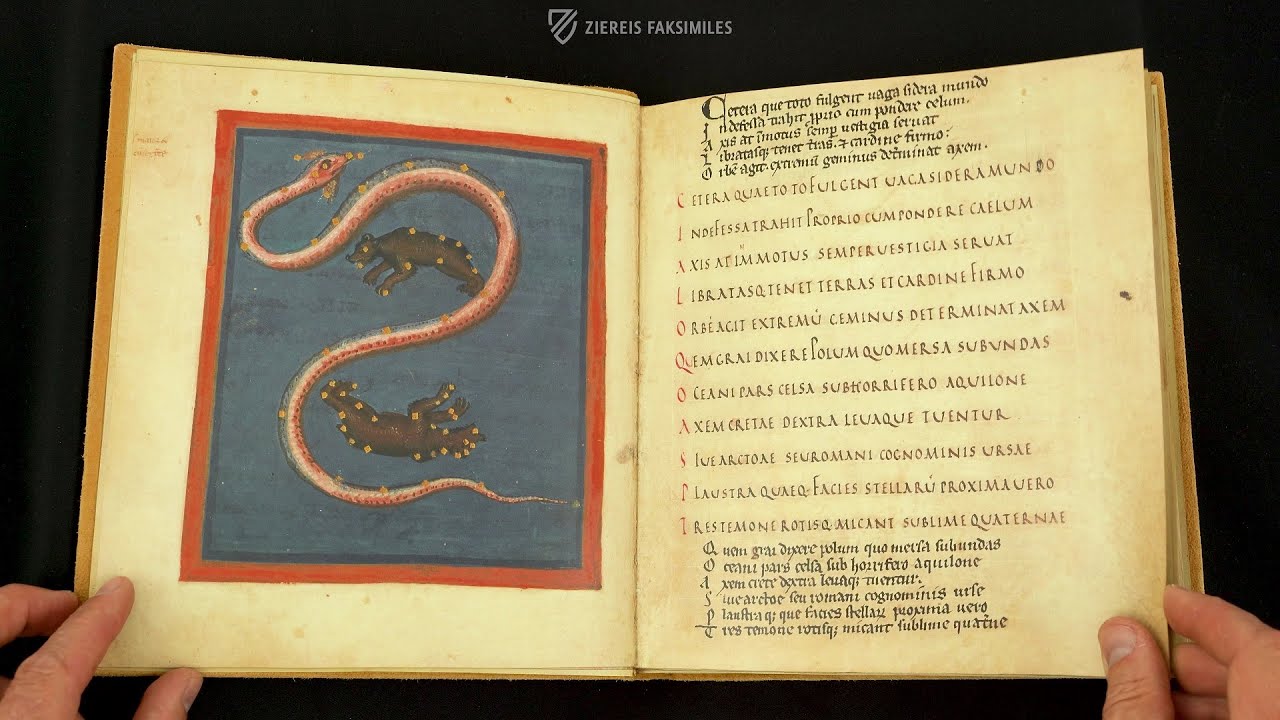

Louis the Pious, Charlemagne’s son and heir, commissioned the Aratea, an astronomical handbook considered to be a milestone in the field, as evidenced by multiple translations over the centuries. Its 39 full-page miniatures with gold leaf show the figures and forms of ancient Greek mythology that serve the author of the Aratea as the foundation of his astronomy.

The book could also be used for navigation purposes and was therefore an object of both beauty and practicality. These are just two examples of how Carolingian scholars were fascinated by the knowledge of antiquity, rather than moralists who simple rejected pagan wisdom.

Experience more

Reestablishing Law and Order

To the facsimile

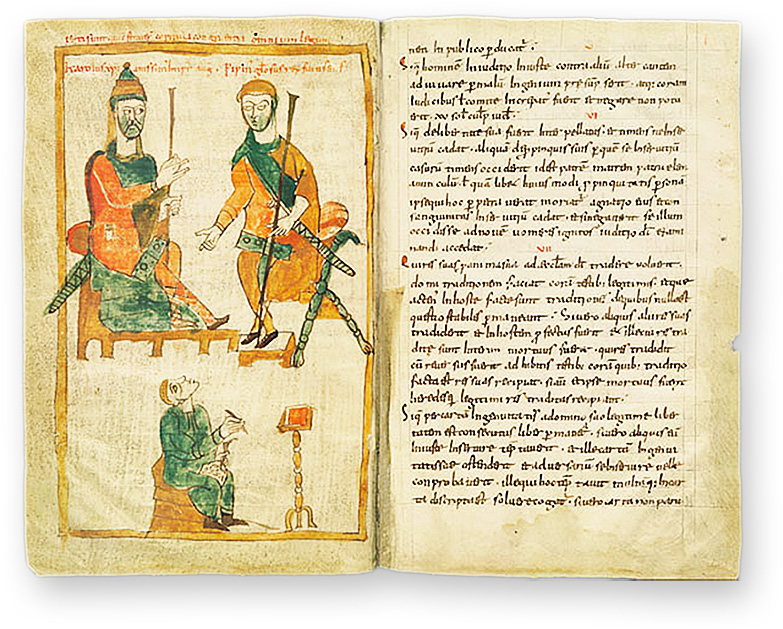

During the 10th century, when the Carolingian Renaissance was interrupted by a period of instability characterized by Viking raids and internal strife between the descendants of Charlemagne, law and order were more important than ever. It is for that reason that the oldest German legal codes, the Lex Salica, Lex Lombardia, Lex Bavaria, and Lex Ripuria were written down and recorded in a single manuscript for the first time in the Leges Salicae.

This established a legal code with punishments and fines for criminal offenses, while also stipulating the right of succession. This so-called Salic Law became the basis of legal systems across Europe and not just in the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, where it remained the basis of the legal system until the 18th century.

These legal traditions would later be recorded and adorned in manuscripts like the Mirror of Saxony and other “mirror” texts. Such medieval legal texts have taught us inter alia that people were actually very litigious during the Middle Ages and aspired to live in a society governed by law.

The Legacy of Carolingian Illumination

Just as Charlemagne’s empire eventually broke into various political entities, Carolingian illumination also produced manifold artistic styles. Its clearest successor, the one which most closely maintained the blended aesthetics of monumental Byzantine illumination and busy Celtic artistic devices, is Ottonian illumination, named after the dynasty of Otto I, who unified the provinces of East Francia into something resembling modern Germany for the first time in the 10th century.

Ottonian illuminators continued to develop and refine the monumental, imperial style of Carolingian illumination. West of the Rhine, Romanesque illumination, while still influenced by Byzantine art, was also characterized by its embrace of the innovative and anti-classical décor of Insular illumination, and would continue to favor certain manuscripts genres that were popular with the Carolingians, e.g. Psalters.

The Romanesque style was the first to reach every corner of Europe, with each region developing its own variation, and from it would emerge the elegant Gothic style, which would be the first truly universal European aesthetic. Just as Charlemagne can be considered to be the “Father of Europe” today, so too can Carolingian art be considered to be the progenitor of subsequent European artistic epochs.

Experience more