The 14th Century in Europe: Art and Beauty in Times of War, Plague, and Societal Change

This is Part 10 of our Centuries series. In it, we will review the 14th century, the twilight of the High Middle Ages, the beginning of the Late Middle Ages, and a period of unprecedented tumult. After reviewing the end of the Crusades, we move to the Wars of Scottish Independence, the reign of Philip IV of France, and the Avignon Papacy.

The famines of the 14th century are examined next in relation the Black Death and its consequences before turning to the birth of Renaissance Humanism in Florence.

We then take a look at the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War along with the rise of the Duchy of Burgundy and the changing nature of medieval warfare. North of the Alps, we examine events in Germany, namely the ratification of the Golden Bull and the formal foundation of the Hanseatic League.

Finally, we return to the wealth and warfare of Italy, the role of foreign mercenaries there, and the influence that great Italian minds like Petrarch and Boccaccio had on Geoffrey Chaucer.

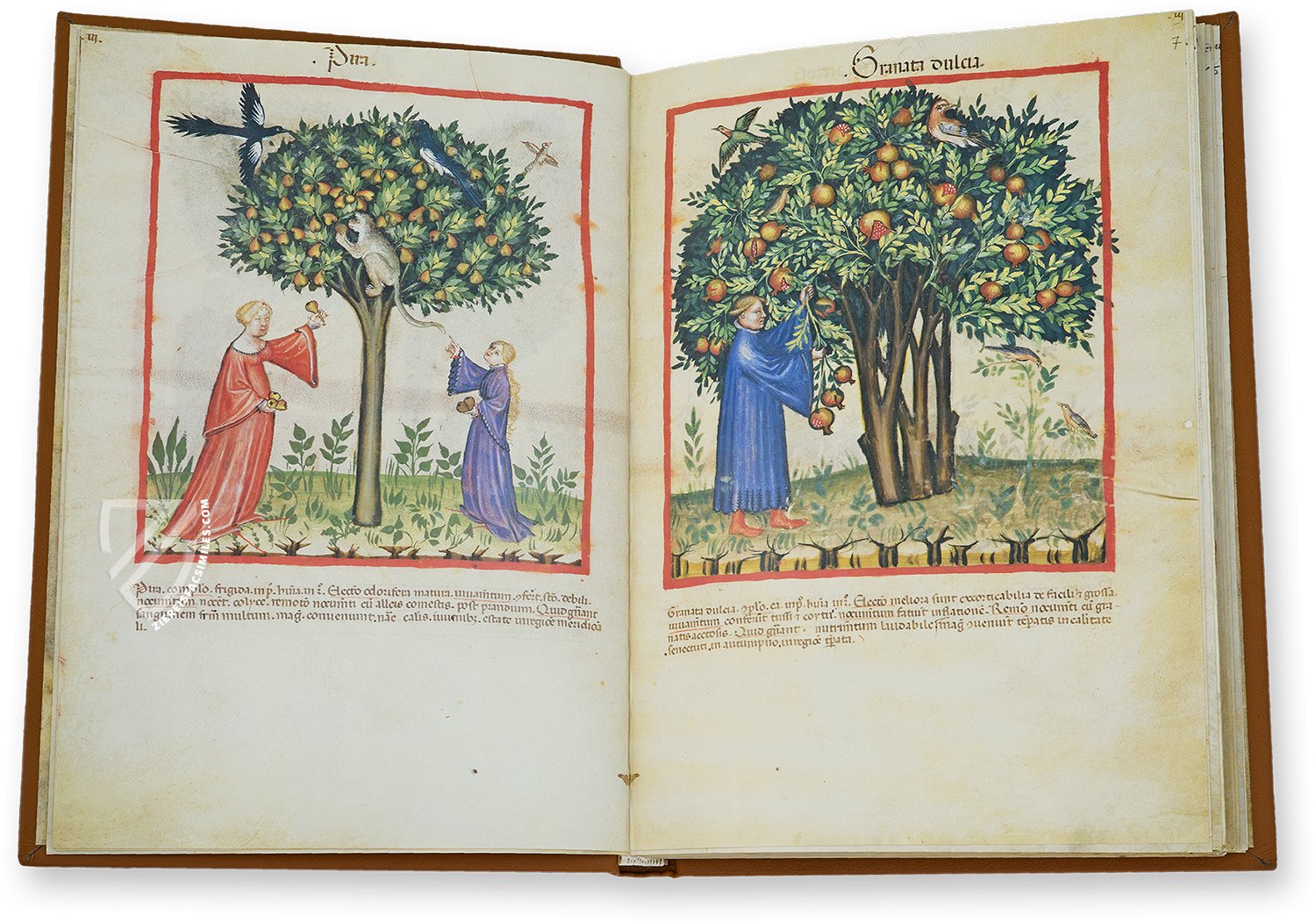

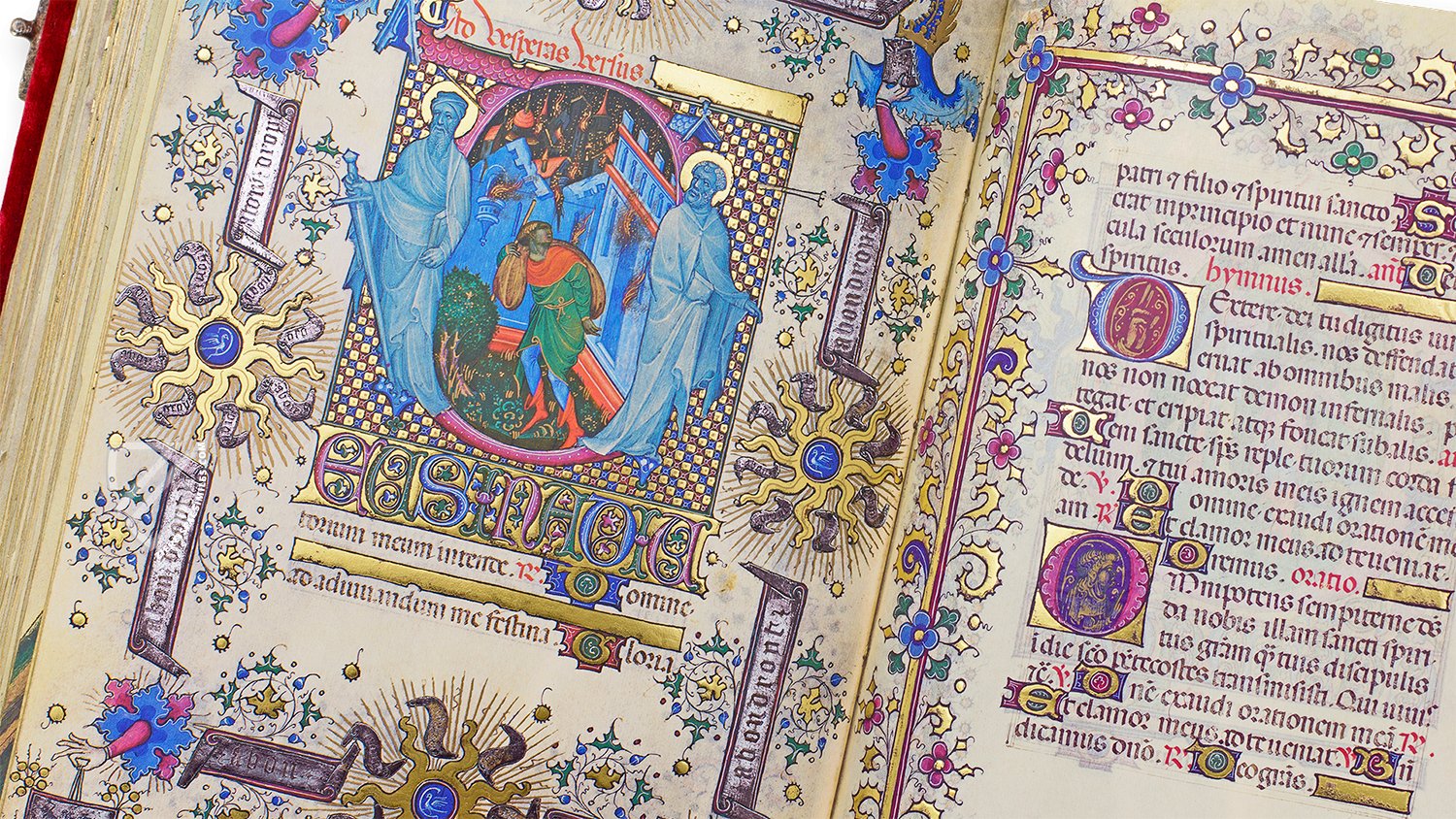

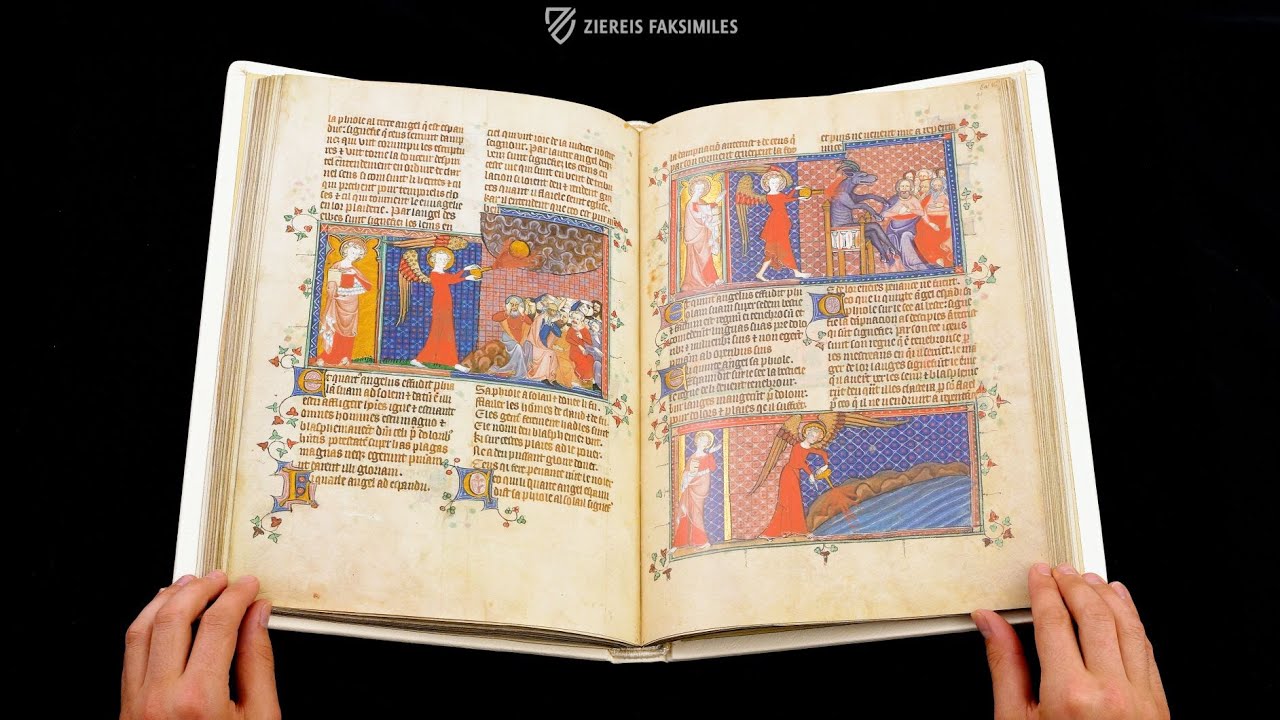

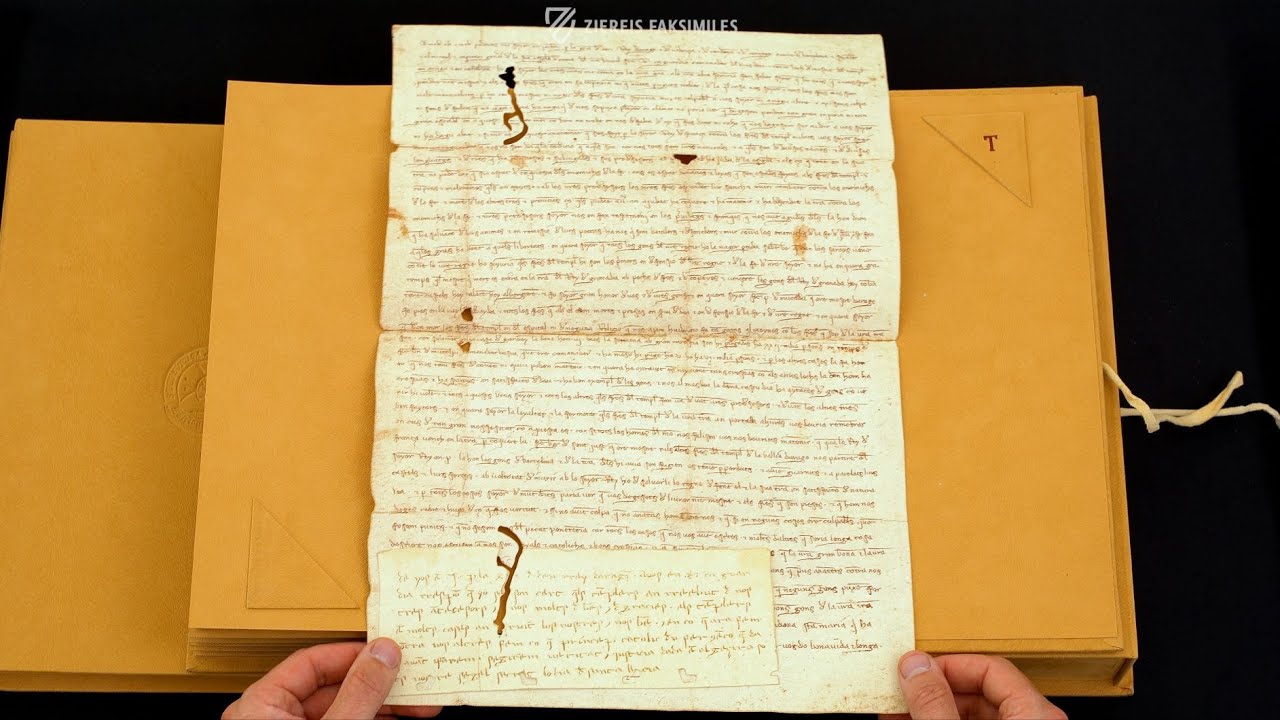

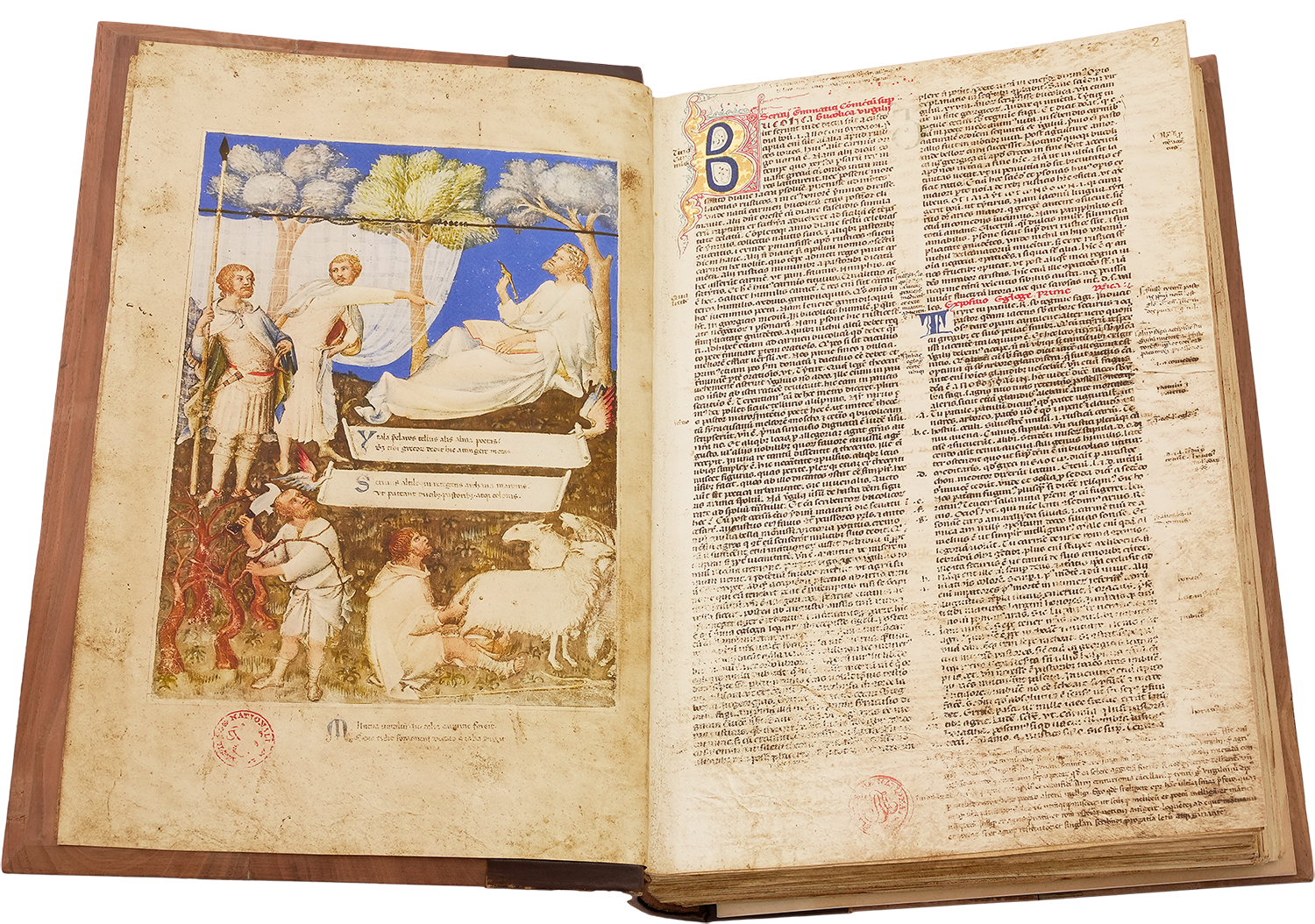

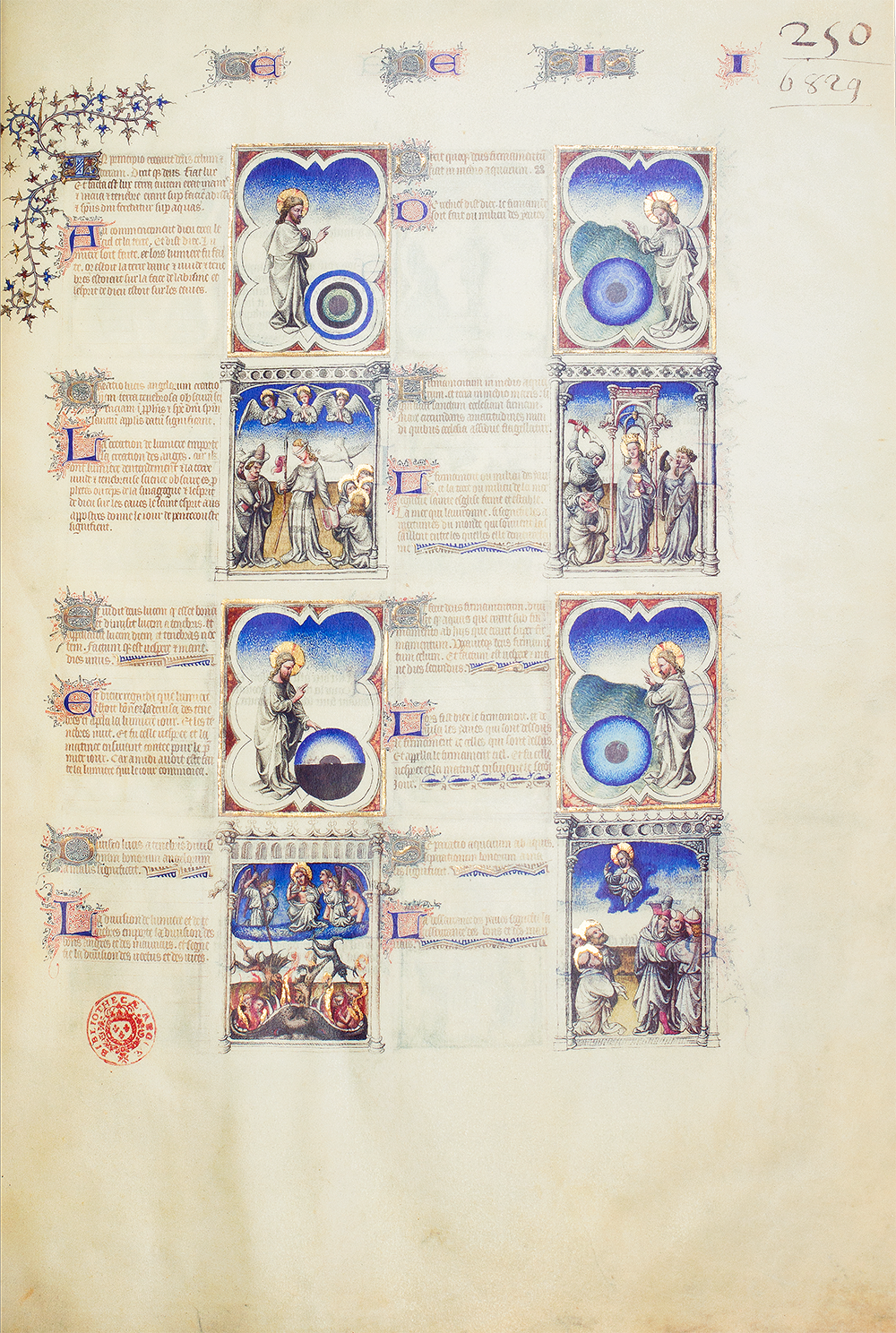

Demonstration of a Sample Page

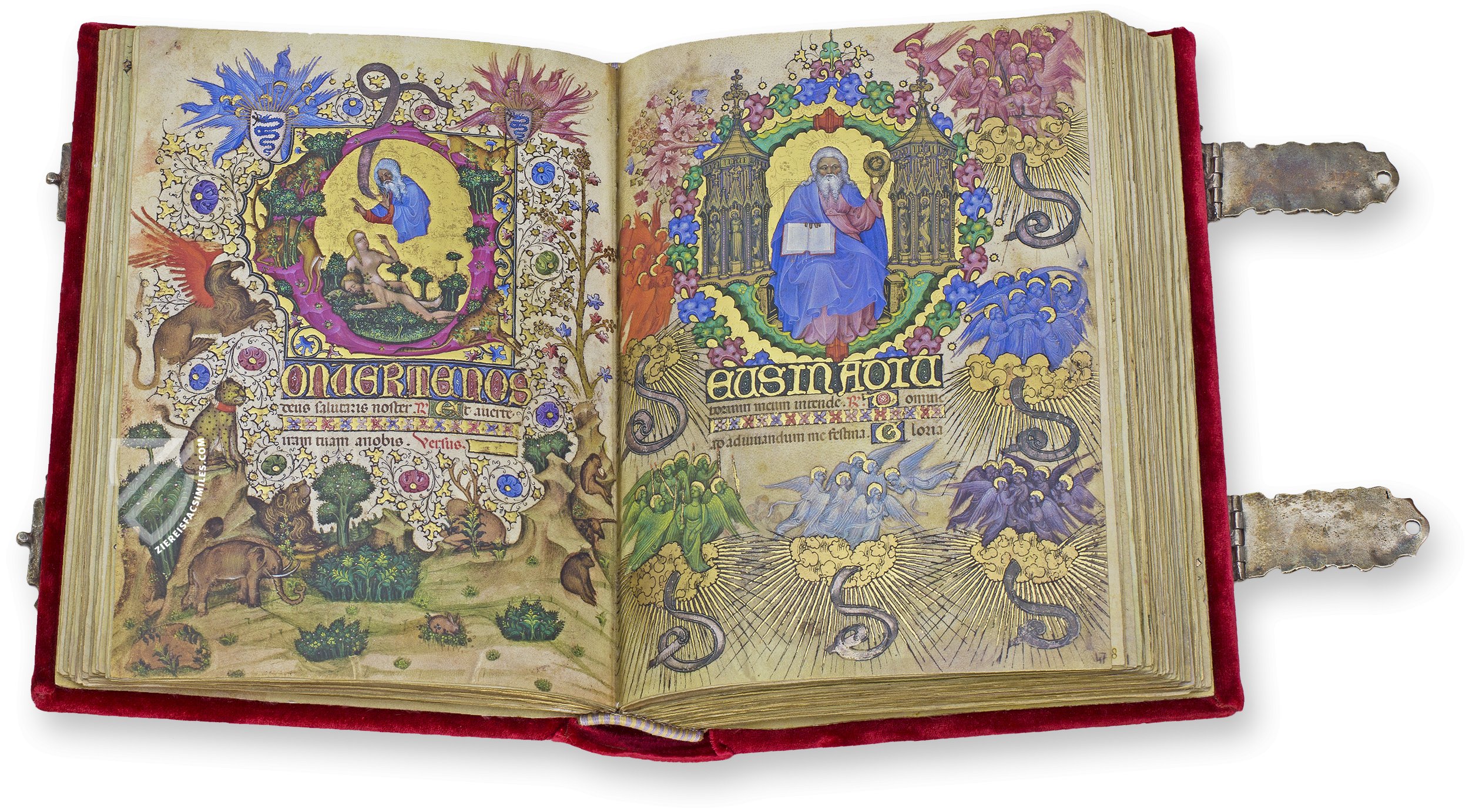

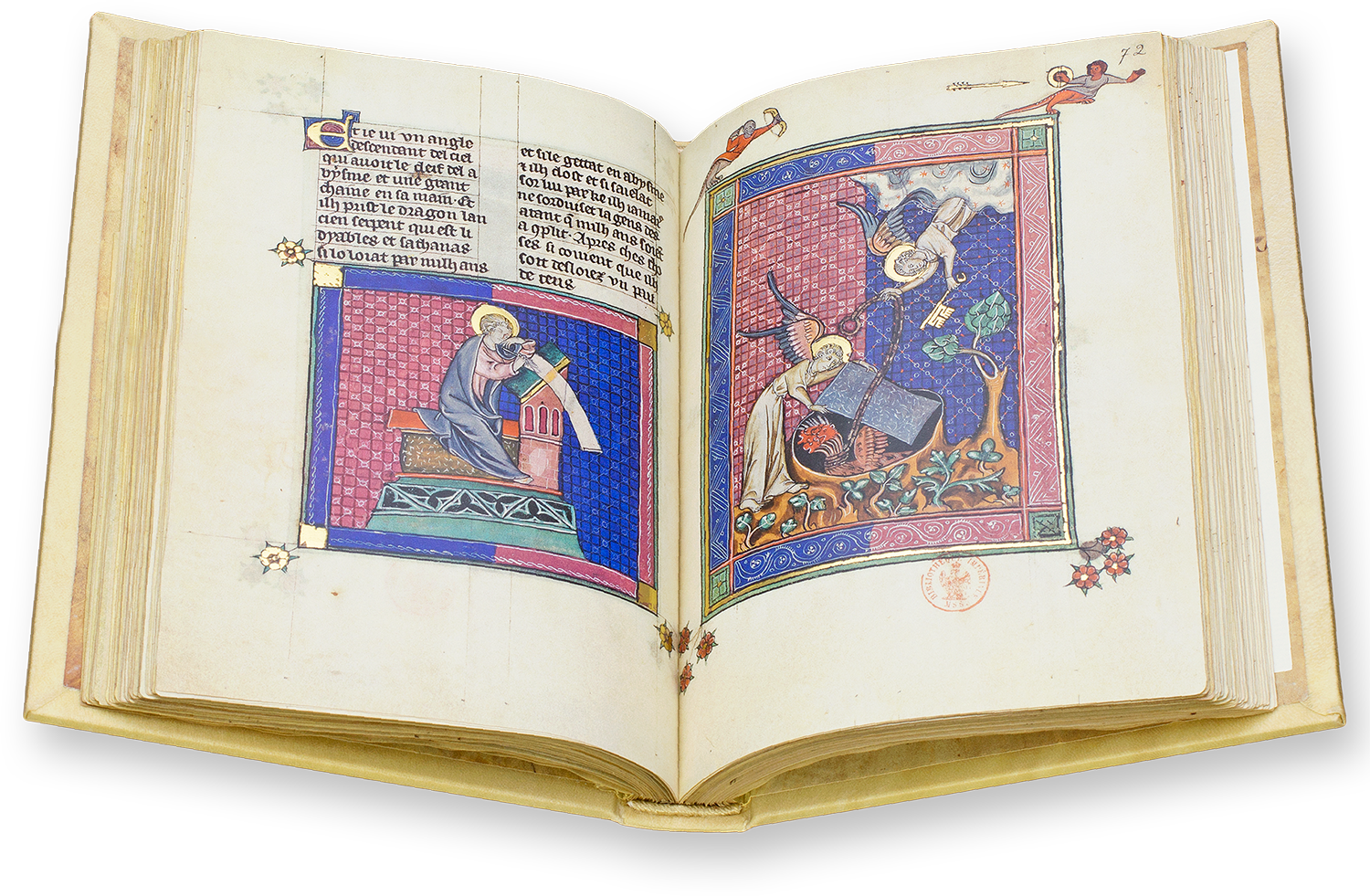

Corpus Apocalypse

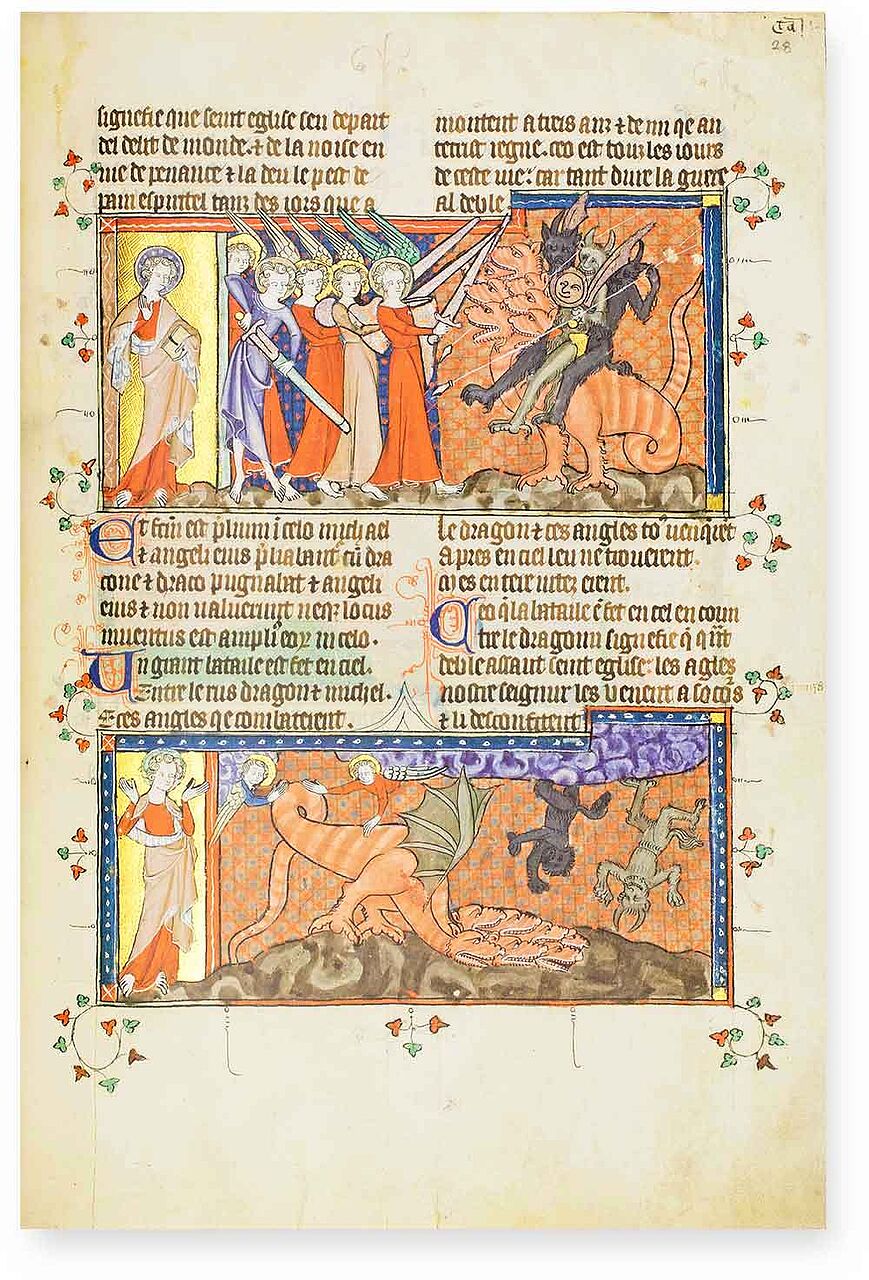

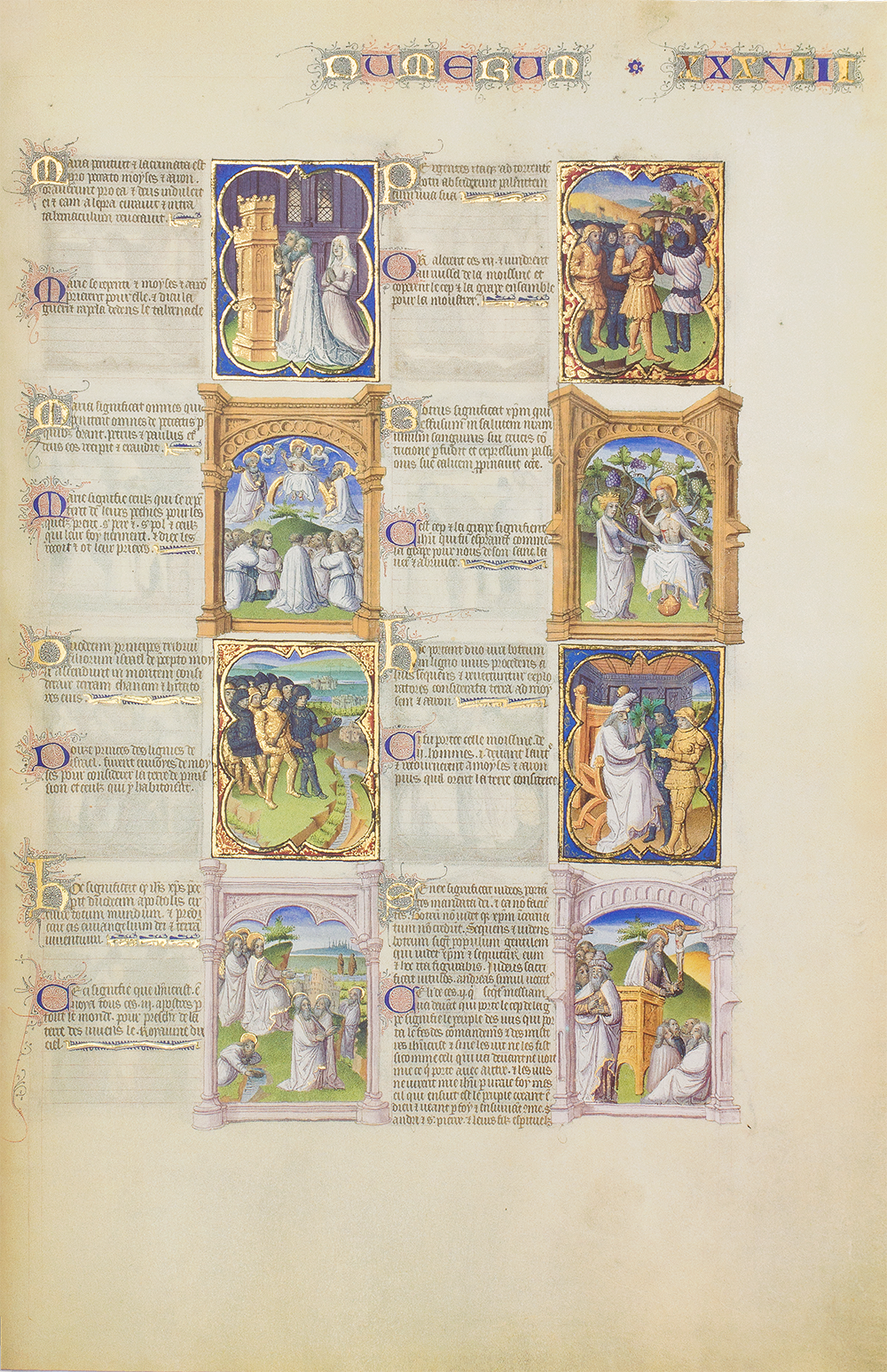

War in Heaven

“And war broke out in heaven: Michael and his angels fought with the dragon; and the dragon and his angels fought, but they did not prevail, nor was a place found for them in heaven any longer. So the great dragon was cast out, that serpent of old, called the Devil and Satan, who deceives the whole world; he was cast to the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.” (Rev. 12:7-9)

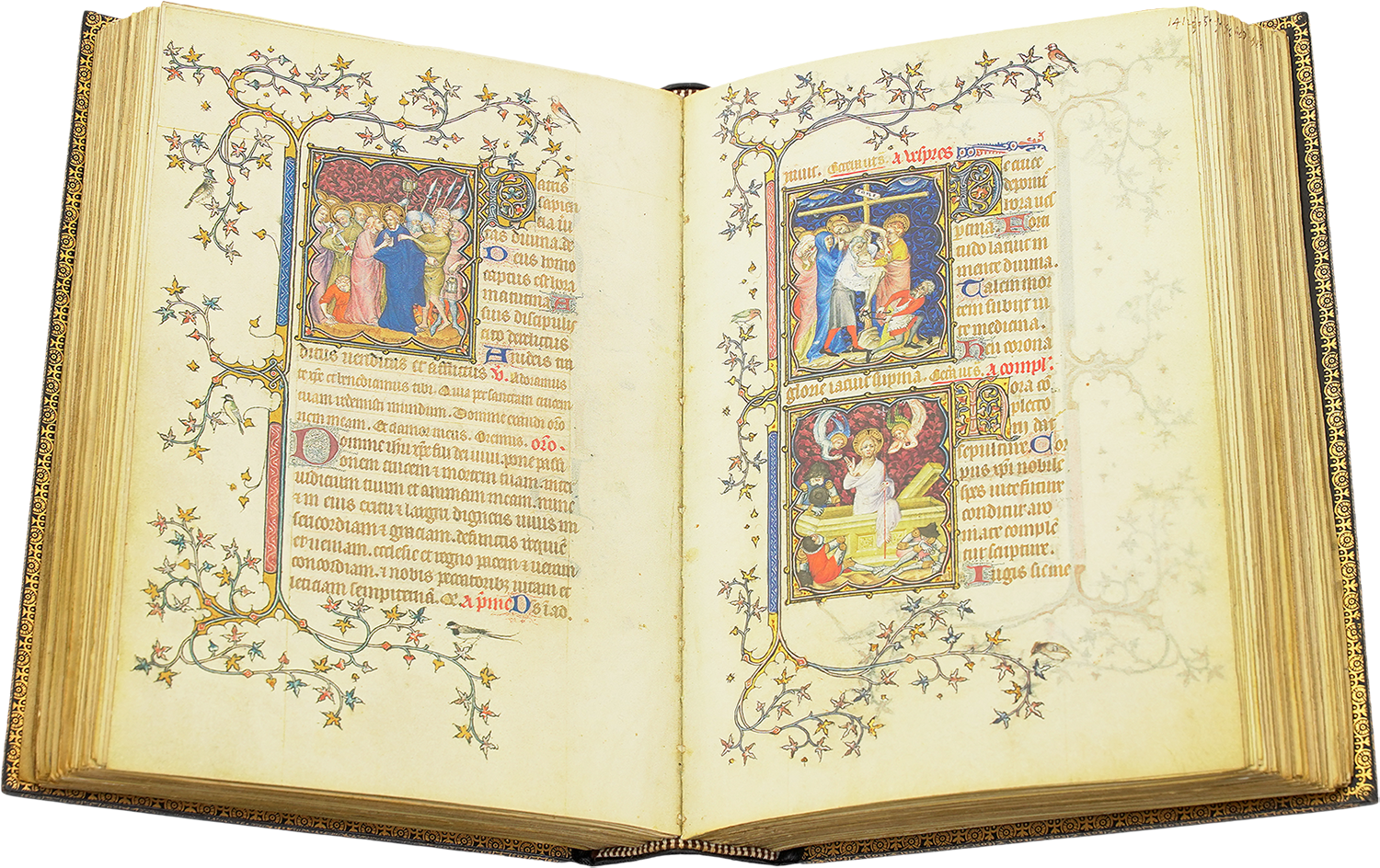

The War in Heaven is one of the more dramatic events of the Book of Revelation, and is depicted here in the masterful style of the English Gothic. These already richly-illuminated manuscripts typically feature and image strip supported by text, but two are employed here to depict the victory of the Heavenly Host as told by John, pictured on the left in a field of gold.

Europe’s Darkest Hour

Few periods have been as tumultuous as the 14th century, but while most maintain that it was a time of great pessimism, it is resilience in the face of famine, war, and plague that most distinguishes the attitude of people who survived and thrived during that troubled epoch. We have on the one hand the macabre late medieval obsession with death, and on the other is the vitality and exuberance of Chaucer.

It was a time when chivalry was replete with contradictions: obedience v. independence, deference v. self-interest, masculine aggression v. gentlemanly court culture. The line between knight and mercenary began to blur, and it is Chaucer again who offers the satire to understand these contradictions.

It is precisely its contradictions that make the 14th century a particularly fascinating period

At the same time that Gothic art and architecture were coming into their fullness of expression and manuscript production was surging, that the Order of the Garter was founded by Edward III (one of the greatest employers of mercenaries), and that etiquette and court culture were being introduced, warfare became endemic and devastating to the common people to a previously unknown degree, noble knights were being challenged by mercenaries and even by commoners fighting as infantry, and the entire population was living in the shadow of famine and plague.

These contradictions are what make 14th century Europe one of the most fascinating and most studied historical topics today, and this study reveals just how much of our own contradictory and confusing modern world is rooted in a period that is falsely regarded as being so foreign as to be alien to modern people.

Experience more

Permanent Loss of the Holy Land

After the failed Crusades of the 13th century, the last remnants of the Crusader Kingdoms on the mainland, the port cities of Tripolis and Acre fell in 1289 and 1291 respectively. Many of the survivors were evacuated to the island of Cyprus, which held out until 1489 and continued to be a launching point for other, more minor campaigns, such as the Alexandrian Crusade that sacked Egyptian Alexandria in 1365.

To the facsimile

In 1310, the city of Rhodes finally submitted to the Knights Hospitaller, who already captured the rest of the Island in 1306. The Hospitallers engaged in an ambitious building program, transforming it into an ideal Gothic city while also heavily fortifying it, even using stones from the ruined Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the ancient wonders of the world, for its construction. As a result, Rhodes successfully resisted multiple sieges throughout the 15th century.

However, these actions were merely attempts to stem the tide of the Ottoman Turks, who even now were raiding into Thrace as the anemic Byzantine Empire failed to respond to the threat. What’s more, the loss of the Holy Land and the increasingly commercial nature of Crusader campaigns resulted in a depletion of zeal for the struggle. This was compounded by domestic unrest, endemic wars, famines, and the Plague. Europe was simply too preoccupied with troubles at home to worry about who held the keys to Jerusalem’s city gates.

The Wars of Scottish Independence

Although the name applied to them is a modern invention created in the wake of the American Revolution, the Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of conflicts divided into two periods, 1296-1328 and 1332-1337, whereby the Kingdom of Scotland was able to retain its status as realm independent of the powerful Anglo-Norman dynasty to the south.

The wars began with a Scottish succession crisis following the death of King Alexander III. Initially invited by Scottish nobles to arbitrate the dispute as the liege of their lands in England, King Edward I of England took advantage of the instability to attempt to subjugate Scotland the way Henry II had Ireland in the 12th century. Although hampered by the Scottish alliance with France, Edward I was able to reverse the successes of William Wallace and defeat him at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298. In spite of this successful campaign, and the capture and execution of Wallace in 1305, resistance continued after his death.

Fortunately for the Scots, the successor to the English throne, Edward II, was unlike his competent and bellicose father. Robert the Bruce subsequently arose to lead the Scots, gathering forces until he was able to meet and decisively defeat the English at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, an early victory for infantry over cavalry.

War resumed when members of the Scottish nobility who had supported the claims of the first two Edwards convinced Edward III to invade in 1332. This war only furthered the destruction in Scotland and the English were eventually forced to recognize Scotland’s sovereignty, which it would maintain until the 1707 Treaty of Union that created the United Kingdom.

France’s Transformation under Philip IV

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

King Philip IV of France, crowned in 1285 at the age of 17, was given the epithet “the Fair” not for his demeanor and personality but rather because of his looks. He waged wars against his vassals to submit them to the new central power in Paris as well as against the English and Flemish. He also commanded an unprecedented army of bureaucrats and hated taxmen.

In his pursuit to strengthen and centralize France, he proved himself willing to engage in activities that were distinctly unfair and underhanded. Philip took advantage of an agreement with the English whereby King Edward I would give his continental possessions to Philip as a sign of his homage as Duke of Aquitaine and Philip would then return the land after a grace period to confirm their feudal contract. Philip had no intention of honoring the agreement, but his get-rich-quick scheme turned into a drawn out conflict whereby the English eventually regained Aquitaine but both sides were exhausted.

Philip IV was willing to use any means to expand his central power in Paris

To finance his wars, Philip began to overtax the Champagne fairs, which were the lynchpin of transalpine trade due to the geography of the region’s rivers that stretched northward to the Low Countries and southward to Italy. This only served to rob the Champagne fairs of their competitiveness, and trade routes began to shift – either via a sea route to Bruges or to other cities like Lyon, Cologne, Frankfurt, and Geneva. Since this tax scheme did not work, Philip then began to persecute Italian merchants and then in 1306, he expelled the Jews from France, seizing their property. Even this scurrilous act was insufficient to fill his coffers, and so he went after a bigger and richer fish: the Templars.

Fall of the Templars

Aside from their possessions in the Levant, the monastic military orders also controlled properties across Europe, which were all that remained to them after the loss of the Holy Land. The Templars were richer and had more property than anyone and commanded an army to match most kings, but without a new Crusade to occupy them, their purpose was now unclear and their support began to wane. They were still involved in commercial ventures ranging from vineyards to banks, and had many business contacts as a result, but their sovereign status and standing army made them a threat, especially as they considered establishing a monastic state, as the Teutonic Order had done in the Baltic.

King Philip IV of France was deeply indebted to the wealthy Templars and sought to take advantage of some unsavory rumors about them, mostly concerning their esoteric initiation rituals, to wipe his debts clean. Pope Clement V, a relative of Philips’s and head of a weakened church, was forced to go along with the scheme. The blow fell on the 13th of October, 1307 – a Friday, thus giving birth to the tradition that any Friday the 13th is unlucky. The Templar leadership, accused of heresy, idolatry, homosexuality, and a litany of other charges that were typically levelled in such medieval trials, were tortured and executed.

To the facsimile

Other Templars were pursued across Europe, but most were not punished. Many joined the Hospitallers, and Templar property was mostly handed over to them as well. Other order members simply “retired” and a popular legend maintains that many Templars found refuge in Scotland, where they helped to aid Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn.

Experience more

The Papacy Moves to Avignon

The instability of Italian politics in general and of Rome in particular created an untenable situation for the papacy. This was the result of the failed ambition of the heirs of St. Peter to assert their secular authority over the princes of Europe. During the second half of the 13th century and the early 14th century, the popes spent most of their time either at their palaces outside of the city, or maintaining temporary residences at various Italian cities.

Under the influence of the powerful King Philip IV of France, the conclave was forced to elect his relative as Pope Clement V in 1305, who subsequently had the papacy moved from Poitiers to Avignon in southern France in 1309. All 7 Avignon popes would be French and the correct perception of Avignon as a tool of the French monarchy was widespread. From their luxuriously appointed fortress in Avignon, the newly reorganized and centralized papal administration proceeded to tax Europe with a previously unknown level of efficiency. The luxurious lifestyle of the pope permeated the curia from top to bottom – graft and licentiousness abounded.

Such conspicuous consumption was contrasted by the pseudo-anorexic asceticism of St. Catherine of Siena. Thus, the term “Babylonian Captivity” – allegedly coined by Petrarch, was also a shot at such luxury.

Meanwhile, Rome slid into insignificance with most of its great churches closed, the papal palace unfit for habitation, streets that were as filthy as they were dangerous, and a population of barely 20,000. The papacy returned to Rome during the reign of Gregory XI in 1377, but a new crisis broke out as two popes were elected after his death, creating a decades-long schism.

The Great Famine

The first of the great crises to afflict Europe during the 14th century was the Great Famine of 1315-17, resulting in millions of deaths and tremendous social upheaval. The event was only the worst of a series of famines and bad harvest suggesting that the Medieval Warm Period came to a close sometime before 1300 because harvests had been in decline since at least 1280 and prices were rising.

The devastating famines of the 14th century led to enormous social upheavals

The decades between 1310 and 1330 constituted an unprecedented period of bad weather characterized by long, severe winters and relatively cool and rainy summers. It is hypothesized that a massive volcanic eruption was responsible, and scholars debate between the eruption of the Indonesian Salas Volcano in 1257 and that of Mt. Tarawera in modern New Zealand ca. 1315. It may have been a combination of both that put so much ash into the atmosphere that it created the “Little Ice Age” in Europe which lasted with some intermittent warm periods until the 19th century.

The result was lower harvests, which lead to decreased tax revenue for the nobility, who in turn increased taxes that further drove up prices, causing bread riots, malnutrition, and a generally weakened population that was more vulnerable to disease. It is in this context that one must understand the coming devastation of the Black Death.

The Black Death

The Bubonic Plague, commonly known as the Black Death or simply as the Plague, that reached Europe in 1348 had already decimated much of the Asian continent, killing hundreds of millions as it travelled along the Silk Road. After making landfall in Pisa, Italy it felled at least one third of the European population.

The plague killed people so quickly – usually within days or even hours – that doctors barely had time to react, a fact that was further compounded by the manifold strains of the disease which had varying symptoms and progressed at different rates. The monastic populations were particularly hard hit because it was the monks and nuns who were treating people. People were dying at such a rate that they were being buried in mass graves and usually unshriven, meaning that they had not been absolved of their sins and given Last Rites – hence the term “short shrift”. This breakdown of ritual and other dignities signaled a larger breakdown of the social order.

However, the focus on the devastation of the Black Death often ignores its causes. The population of Europe in the year 1000 is estimated to have been about 24 million, but this skyrocketed to 54 million by 1340, resulting in overcrowding, fallen living standards, and breakdowns of economic and political systems. Furthermore, the population was weakened by a series of famines during the 14th century that left it vulnerable to disease, as did the longer, colder winters that kept people crowded inside.

By 1450, a century after the first and most deadly wave of the plague, the population had only recovered to 37 million and would not return to pre-plague levels until the 16th century.

Experience more

Finding the Black Death’s Silver Lining

All too often, our image of the Black Death is of suffering, of oozing wounds and the horrible stench of death, of macabre acts of penance like those who would go around flagellating themselves, or those who conversely resigned themselves to orgies and other debauched acts of nihilism. However, the catastrophe was a time of huge opportunity for those who survived.

To the facsimile

The price of labor and the standard of living increased, while land became cheaper. Since less food needed to be grown, more land was available to graze sheep for wool and other products, boosting the economy. Medical theory and practice improved. Medieval doctors recommended a holistic approach to treating the patient, addressing both their patients’ physical and mental well-being, which modern physicians have only recently come to value again. The social order was disrupted and fashion as we know it came into being as cash replaced feudal obligations as the driving force of the 14th century. Sumptuary laws were enacted both to keep the lowborn in their place and to keep them from driving up the prices of luxury goods, but with small effect. Books of etiquette emerged, both a sign of social mobility and of the barriers created to it. Finally, the Plague was also a boon for vernacular language, e.g. for English: the French-speaking clergy was decimated and replaced by a native-born clergy in the aftermath. What’s more, Edward III ordered the official use of English in all law courts in 1362 so as to make the legal system more accessible to commoners.

Experience more

The Renaissance Takes Root in Florence

To the facsimile

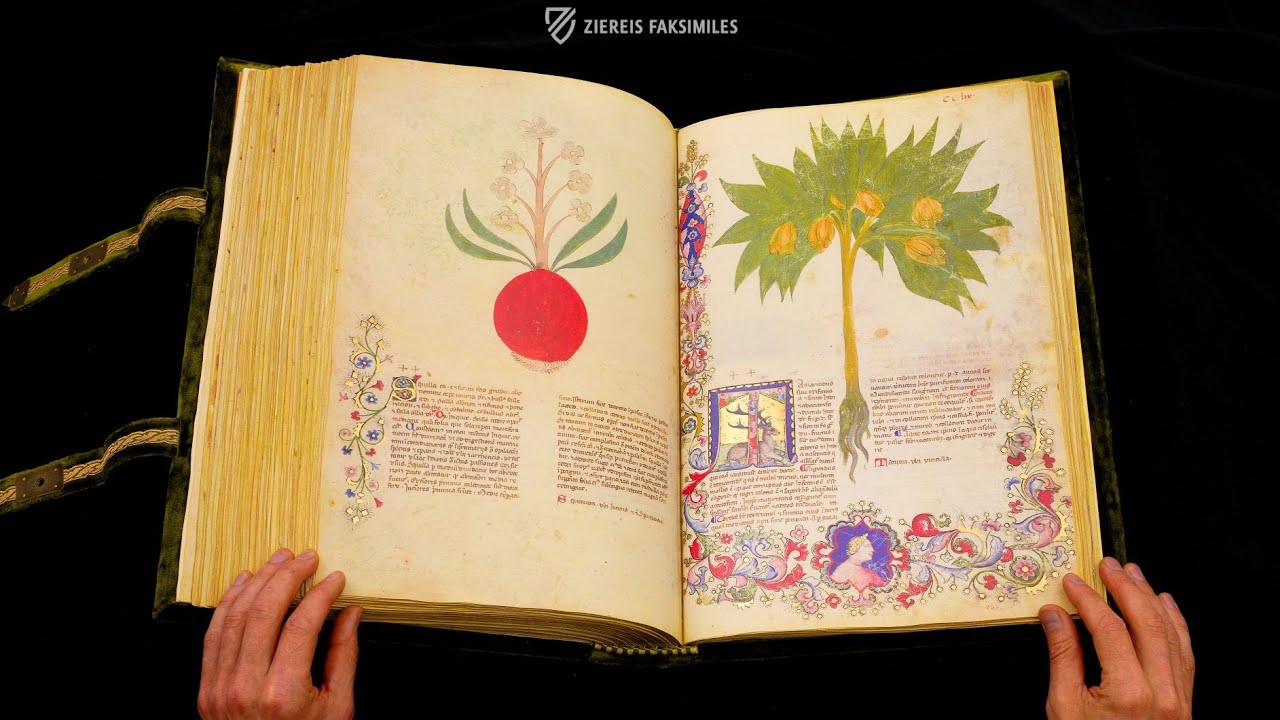

No other development contradicts the overall gloomy picture of the 14th century with as much panache as the Renaissance. Like with so many historical trends, there is are no exact dates for the beginning and end of the Renaissance. It can be said, however, that the Renaissance first emerged in Florence, perhaps as early as the 1320’s.

So, if Petrarch is the Christ figure of the Renaissance, then Brunetto Latini was John the Baptist. The 13th century Florentine chancellor was also a philosopher and scholar who began a civic revolution in Florence establishing civic liberties and creating a proper community that valued discourse, activism, leadership based on merit, and individual genius. These came to be the underlying principles of the Republic of Florence, elevating it above the other rich and cultured cities of Italy.

It was also Florence’s finances that distinguished it: their currency, the Florin, was the first European currency to be struck in sufficient quantities and to maintain a consistent value so that it was acceptable as a universal currency. Unlike other currencies, the Florin did not have a monarch’s likeness on it, but simply the city’s fleur-de-lis on one side and an image of St. John the Baptist on the other.

While earlier philosophers would have worried about sinful wealth tainting their spiritual and scholarly pursuits, the Humanists saw nothing wrong in such activities, arguing in fact that wealth and fame were honorable goals to which one should aspire.

Humanism Takes Root

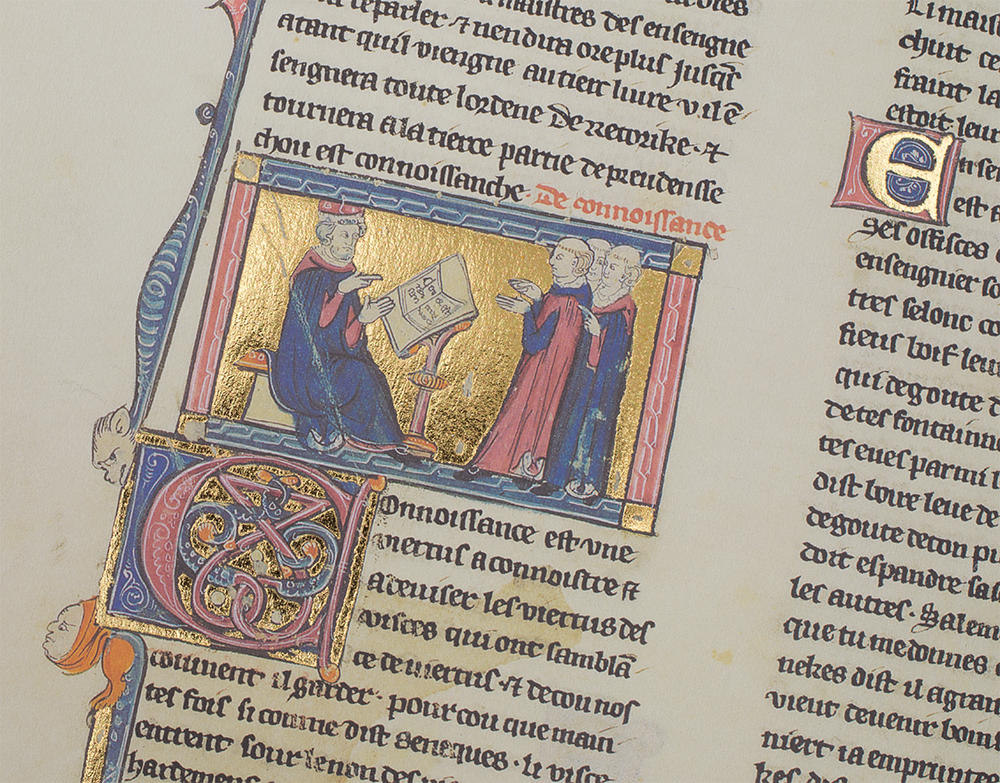

The civic principles established by Latini came to be among the fundamental principles of Humanism, the intellectual movement that defined the Renaissance and has distinguished European civilization and philosophy ever since. Therefore, Humanism did not have its genesis in academia but rather emerged among statesmen and men of letters before being embraced by scholars, who were still rooted in the traditions of Scholasticism.

The new Humanism of the Renaissance dispensed with the secular-religious duality that concerned Scholastics like Saint Thomas Aquinas and focused on the study of classical literature - studia humanitatis. The aim of the studia humanitatis was simply to develop human nature and thereby produce virtuous action. The term “Humanist” has its root in the word umanisti or “one who studies the classics”. Aside from a classical education, this involved encouraging participation in public life that would bring about social change.

To the facsimile

The Humanists praised authors from antiquity like Aristotle, Cicero, and Livy for their eloquence above all their other virtues. Classical learning was not looked upon with nostalgia by the humanists, who rather associated it with the future and felt a kinship with ancient minds who could so succinctly express the intrinsic and permanent reality of human existence. This analysis of perception and experience resulted in a fascination with history as a subject whose study and practice could contribute to life in the present. It is difficult to overstate how fundamentally modern western thought rests upon philosophical principles that were first established during one of the most tumultuous periods in history.

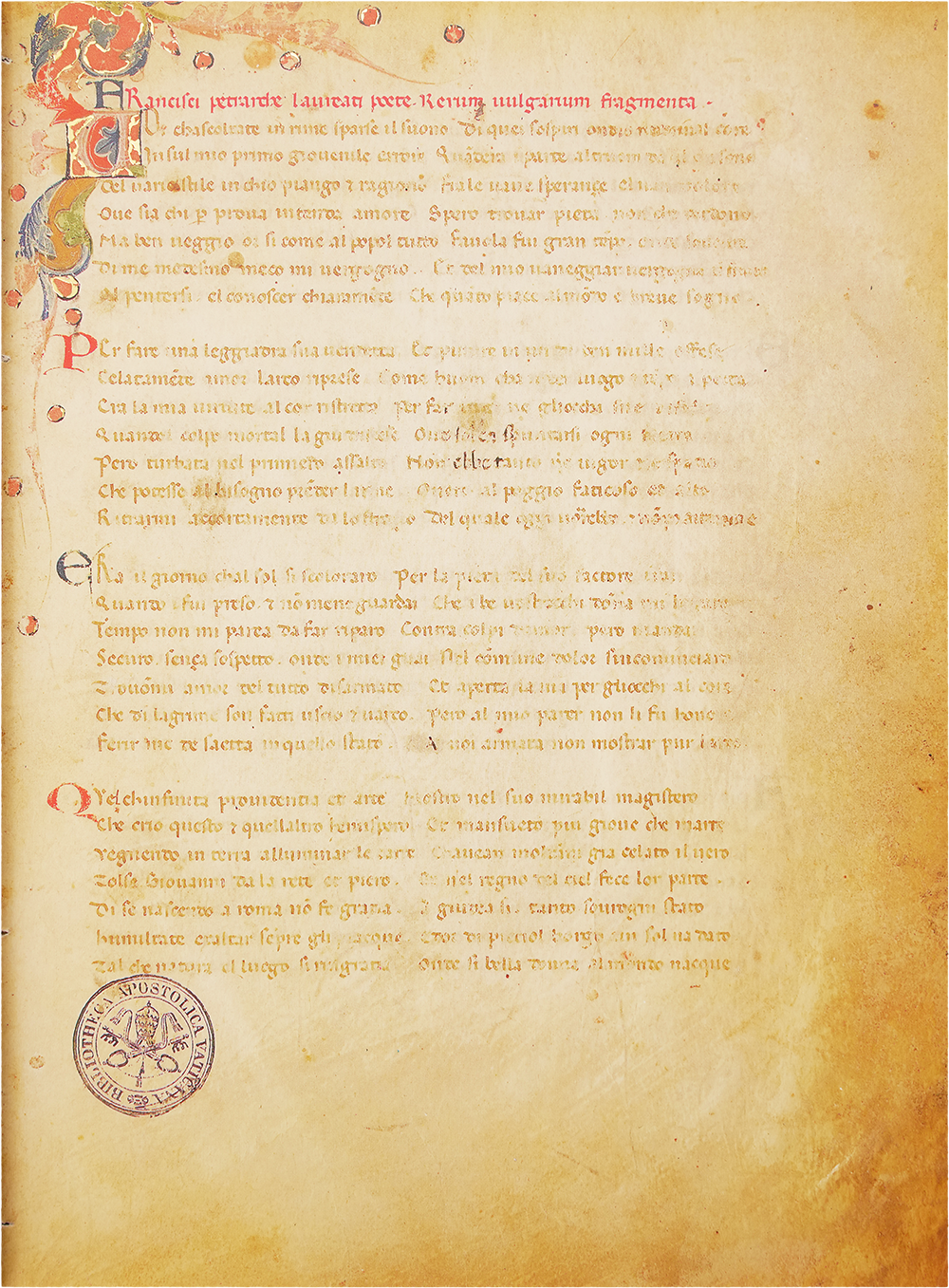

Petrarch and Boccaccio: Pillars of the Renaissance

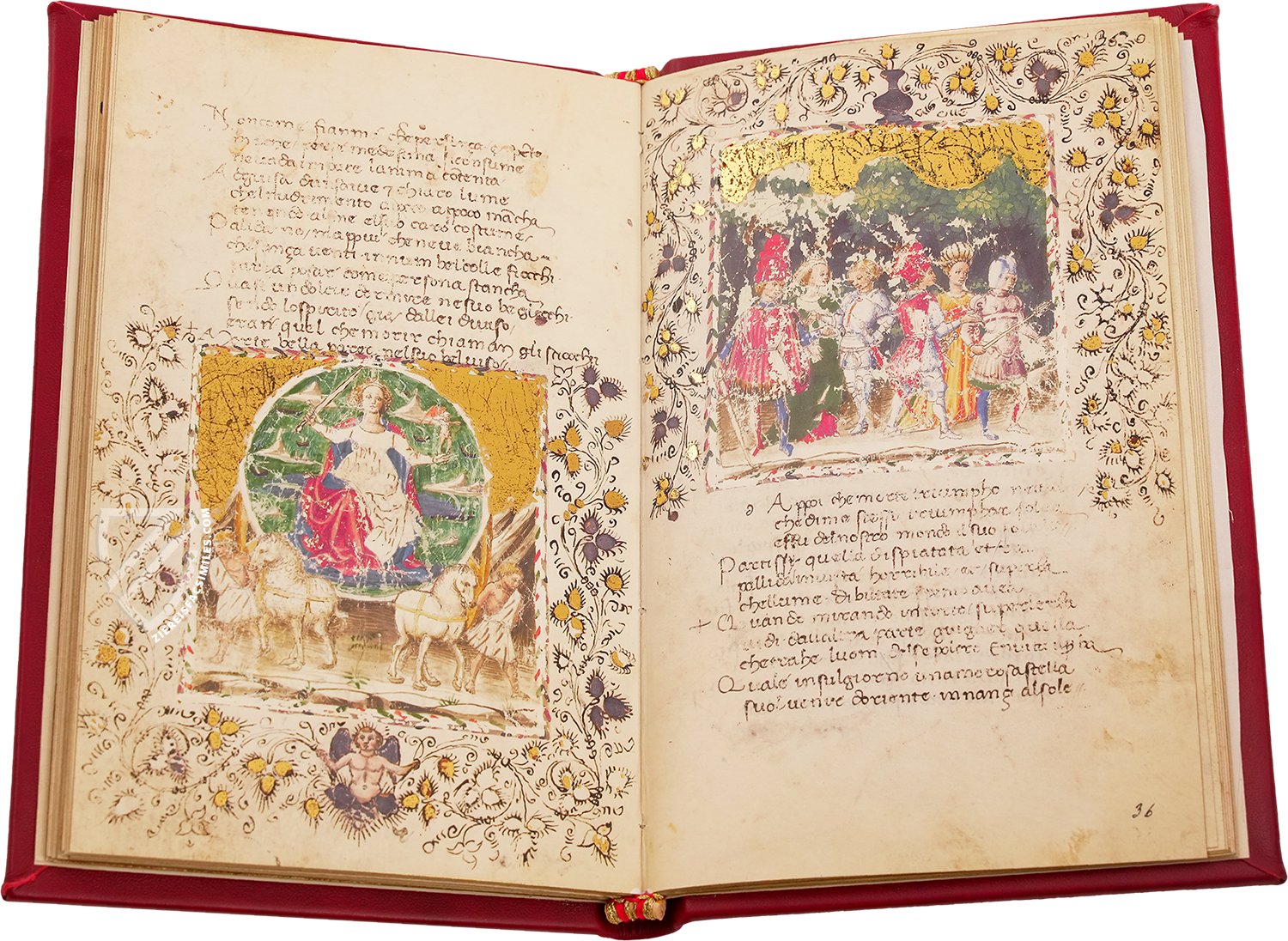

To the facsimile

Petrarch personally discovered a previously unknown collection of letters by Cicero and was only the second poet laureate to be named since antiquity. He coined the term “Dark Ages” to differentiate the relative ignorance of the Early Middle Ages with the brilliance of antiquity. Drawing on classical teachings, Petrarch was the first to emphasize personal autonomy and dignity based on the limitless potential of human beings. He focused on the importance of rhetoric and language, self-knowledge and moral autonomy, and believed in human virtue above fortune. Petrarch was torn by and ultimately unable to resolve the issues of faith v. reason and liberty v. autocracy. His Canzionere (1330-74) are considered to be a model of Renaissance lyric.

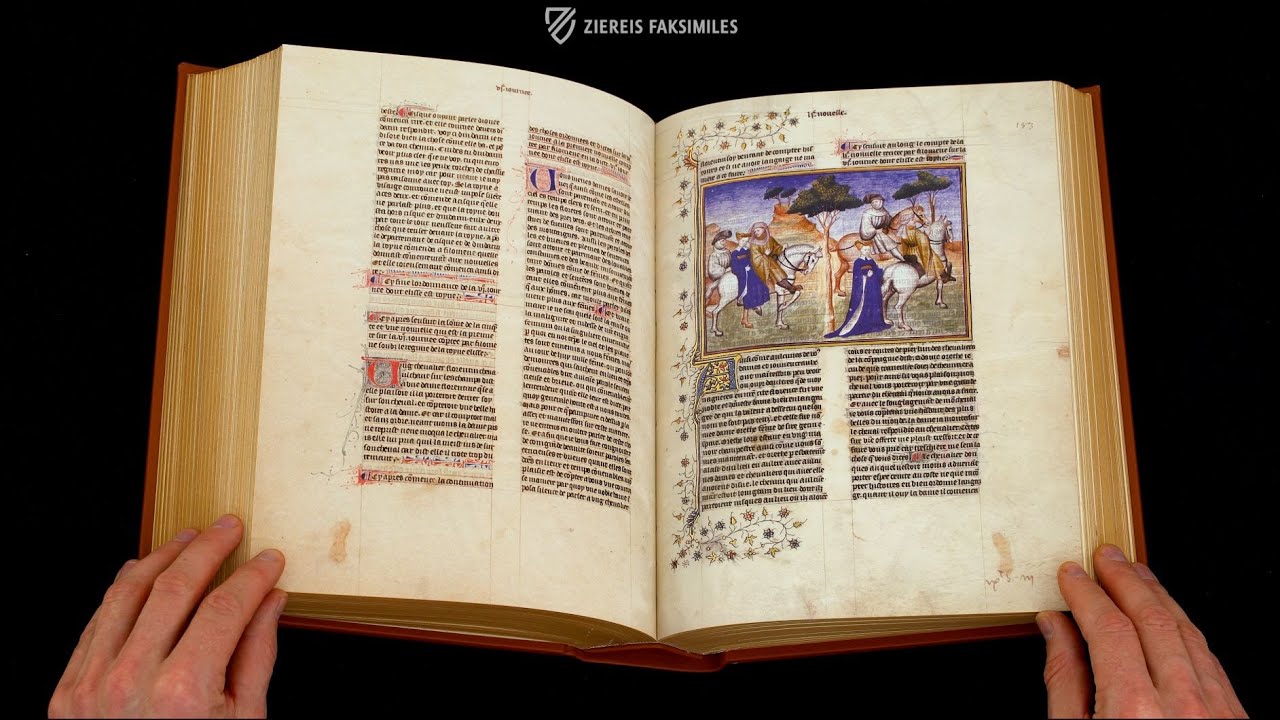

Boccaccio is best known for his monumental Decameron, which sought to reinterpret the human experience based on perceived reality: reason, nature, and a moral order built on human potential. Set against the backdrop of the Black Death in Florence, the Decameron relates the meeting of ten young people at a Villa outside the city, who each tell ten stories over the course of ten days, totaling in 100 tales encompassing morality, tragedy, romance, humor, and wit.

Experience more

The Shadow of the Hundred Years’ War

The Hundred Year’s War (1337-1453) was not a single century-long conflict but rather a series of wars that took place over the course of 116 years and drew five generations into the fray. They devastated parts of France to an extent that was not matched until the 20th century, drew in powers from across Europe, and played a critical role in the formation of the late medieval kingdoms of England and France.

This began with a dynastic crisis: King Charles IV died without sons or brothers in 1328 and his sister Isabella de France put forth her son – King Edward III of England – as the heir. Worthy of note is the fact that Isabella of France was also a descendant of Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, reuniting that bloodline with the English crown and now threatening the French crown as well.

The roots of the conflict lay in the Norman conquest of England during the 11th century

The conflict was rooted in the year 1066, when the Norman Conquest made one of the most powerful nobles in the Kingdom of France into the King of England, who could now use the resources of that country to support his lands and ambitions in France. A Franco-Scottish alliance that was signed in 1295 further exasperated cross-channel relations.

The English were not taken seriously as a threat at first, France was the largest and richest kingdom in Europe with a population several times larger than England. However, what had seemed to be a prudent political marriage to her father Philip IV ended up being the source of untold sorrow for the French as their country was afflicted by the Anglo-Normans, the most advanced military force of the High Middle Ages.

Decline of the Knight: the Battles of Crécy and Poitiers

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

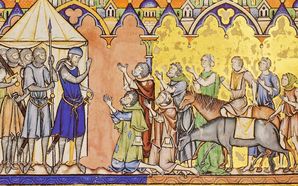

French knights who competed for glory with one another in lavish tournaments and on the battlefield were considered the best in Europe. Frankish heavy cavalry dominated the European battlefield and the Franks earned both the praise and scorn of Pope Urban II as he called for the First Crusade. However, the purely feudal armies of the French had long been unwieldy in battle.

Meanwhile, the armies of Edward III consisted of a tactically flexible mix of feudal levies and mercenary troops balanced between infantry, longbowmen, and cavalry that made good use of the terrain. They were commercial enterprises driven by the promise of pillage whereby the lowborn could rise.

Europe was shocked on August 26th, 1346 when the army of the English, numbering 10-14,000, decisively defeated a French army at least twice its size at Crécy. The English were in a strong defensive position on a slopping hillside that could not be outflanked and the English knights fought on foot with the infantry. The French charged recklessly at these positions, facing the concentrated fire of 5-7,000 longbowmen, who supposedly fired as many as 500,000 arrows on that day. The result was a crushing French defeat, one that would be repeated at Poitiers in 1356, when Edward the Black Prince killed or captured much of the French nobility, including King John II himself and his son Philip. These two disasters left France reeling for years and another was to come before the French began to reform their army.

Experience more

Burgundy Emerges as a Major Power

Captured along with his father at the Battle of Poitiers, Philip the Bold was rewarded with the Duchy of Burgundy in 1363 by his father King John II of France for his bravery in the disastrous battle. By virtue of his marriage to Margaret of Dampierre, his lands were appended by the Free County of Burgundy – the Duchy’s imperial counterpart – in addition to the Duchy of Brabant, the County of Flanders, and the County of Artois.

He acted as regent during the minority of King Charles VI from 1380-88, after which he was sacked in favor of other counselors, before reassuming control of France from 1392 to 1402 and again in 1404, shortly before his death. This created a rivalry within the ruling House of Valois between the families of Philip and his cousin Louis, Duke of Orléans, which would have disastrous consequences for France.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Philip the Bold’s Burgundy now stretched from the Alps to the Low Countries, controlling important trade routes and some of the richest agricultural land in Europe, especially with regard to wine. In fact, it was Philip the Bold who ordered the cultivation of Pinot Noir in 1395, for which Burgundy is now famous, outlawing the prolific yet acidic Gamay variety in order to protect the reputation of Burgundian wine. Burgundy rose to become one of the wealthiest and most powerful realms of the 14th and 15th centuries with a sophisticated court culture second to none, and would come to rival even the Kingdom of France and serve as England’s most important ally during the Hundred Years’ War, thus bearing the fruit of the rivalry between Philip and Louis d’Orleans.

The Golden Bull Reforms the Holy Roman Empire

Named the Golden Bull because of the golden seal it carried (the word “bull” coming from the Latin bulla meaning seal or sealed document), it is a legal document issued in 1356 by the Imperial Diet at Nuremberg and Metz that was headed by Emperor Charles IV, establishing the constitutional structure of the Holy Roman Empire for the next four centuries.

It specified seven Kurfürsten or Prince-Electors who would have the privilege of choosing the Kaiser, consisting of the three ecclesiastical and four secular princes, and established the principle of majorityvote (to avoid the problems of getting a unanimous decision and the ensuing dynastic struggles) along with specific procedures for voting. Being in the old Frankish heartland of the empire, Frankfurt was felt to be the natural place for such elections and Aachen continued to be the site for coronations. The document also stipulated the rights of the various local rulers, helping to establish them as autonomous states within the empire with rights to mint currency, exact tolls, and build castles.

Significantly, the papacy had virtually no involvement with the creation of the document, and the document made no mention of the need for papal confirmation. However, the Golden Bull did nothing to address the problems of the anemic imperial office, namely shrinking crown lands and the resulting loss of tax income, the lack of a standing army, or a professional bureaucracy. Although the empire was now more durable, the power of the imperial office continued to depend on the individual sitting on the throne.

Experience more

The Founding of the Hanseatic League

Throughout the course of the 12th and 13th centuries, German merchants rose to dominate trade in the Baltic region while also playing a significant role in the trade of the North Sea and along the Lower Rhine. After the capture of Lübeck in 1158, German merchants were able to start spreading northward and eastward, establishing commercial cities at Visby on the island of Gotland, as well as Riga, Reval, Danzig, and Dorpat. During this time, associations of German merchants – known as a Hansa from the Middle Low German for “convoy” – in the West, North, and East began to emerge to protect their shared commercial interests and suppress piracy.

The merchants in the West enjoyed the privilege to trade in England and the Low Countries, but soon faced competition from their Baltic rivals and by the 1280’s were creating an expanded Hansa with them. By the beginning of the 14th century, various regional Hansa had formed the wide-ranging Hanseatic League, which stretched from London and Bruges in the West to Novgorod in the East. The Hanseatic Diet was formed officially in 1356, formalizing the League, which was independent from the German princes to the south and had the power to make war on its (mostly Scandinavian) competitors.

The Hanseatic League continued to be the decisive player in northern European trade until its decline in the 16th century, and was finally disbanded in 1862 with the final three members of Lübeck, Hamburg, and Bremen officially retaining the title of Hansestadt or “Hanseatic City” today.

Trade Flourishes in Italy

During this period of time, Italy was benefitting from an unprecedented level of trade. The Genoese merchant fleet boasted 1,000-ton ships that would not be surpassed in size until the 18th century. Milan’s position on the Po River and the stability of the despotic rule of the Visconti not only attracted artists but merchants as well. Florins from Florence were a dependable international currency when other coins were being debased by short-sighted rulers like King Philip IV of France.

Italians became the bankers of all Europe, which came with risks: the Florentine Bardi and Peruzzi banking families were ruined when King Edward III of England defaulted on loans totaling more than a million Florins and brought down a third firm, the Acciaiuoli.

Such catastrophic domino effects were not the only feature of modern economics to ring true in the 14th century, when many of our modern financial tools were invented or commonly used: checks, bills of exchange, holding companies, insurance, courier services, and double-entry bookkeeping, which they learned from Jewish merchants in the Middle East who had developed the method during the Early Middle Ages.

It was not just their ability to conduct and finance trade, but their ability to manufacture products – e.g. fine textiles from Florence or plate armor from Milan – that made the Italians so wealthy. A single Italian commune generated as much wealth as an entire kingdom north of the Alps, usually more.

Experience more

A Plague of Mercenaries

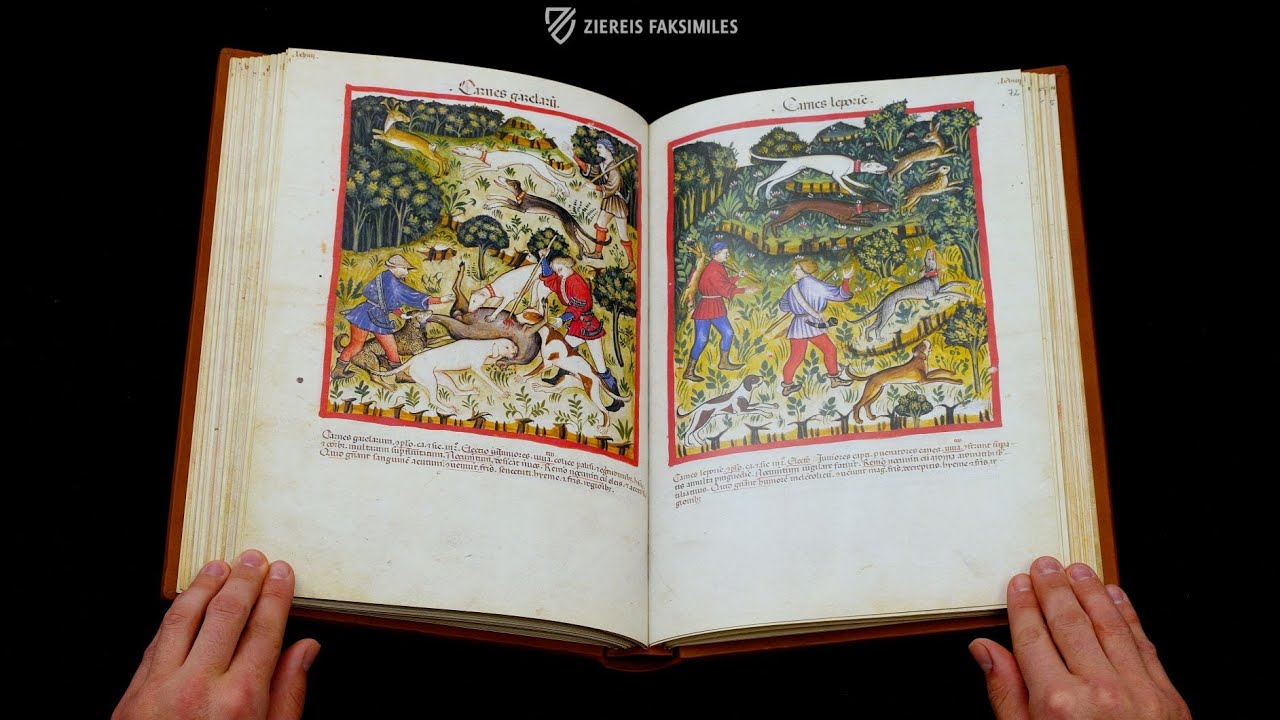

The effects that mercenaries had on 14th century society were no less devastating than the plague, but it was when they were unemployed that they were most dangerous. Periods of peace during the Hundred Years’ War left idle mercenary companies, often referred to as “free companies” because they were not bound by feudal oath, to victimize the people.

This was the case of Pont-Saint-Esprit, a key mercantile city in southern France controlling one of only four bridges over the Rhône, which was suddenly attacked during the night of September 28th/29th, 1360. The so-called Great Company, which numbered in the thousands, had intended to intercept a shipment of gold being raised for King John’s ransom, but the city itself was a rich prize. Rather than sacking the city in an orgy of violence, they calmly took control of the city and began assessing how much they could squeeze from it because these sophisticated mercenary companies also employed accountants, lawyers, and notaries to keep accounts, settle disputes, and draft contracts.

However, this conquest only whet their appetites, and the city of Avignon, brimming with the treasure and tax revenues of the papacy, was a tempting prize that was only 20 miles away. The mercenaries set about blockading the city and would have stormed Avignon were it not for its strong defenses. Pope Innocent VI was unable to dispel the mercenaries: excommunicating them did nothing, the reduced prestige of the Avignon papacy made attracting Crusaders to deal with them difficult, and so he was forced to do the worst possible thing – buy them off. This dangerous precedent only encouraged the rapacious mercenaries.

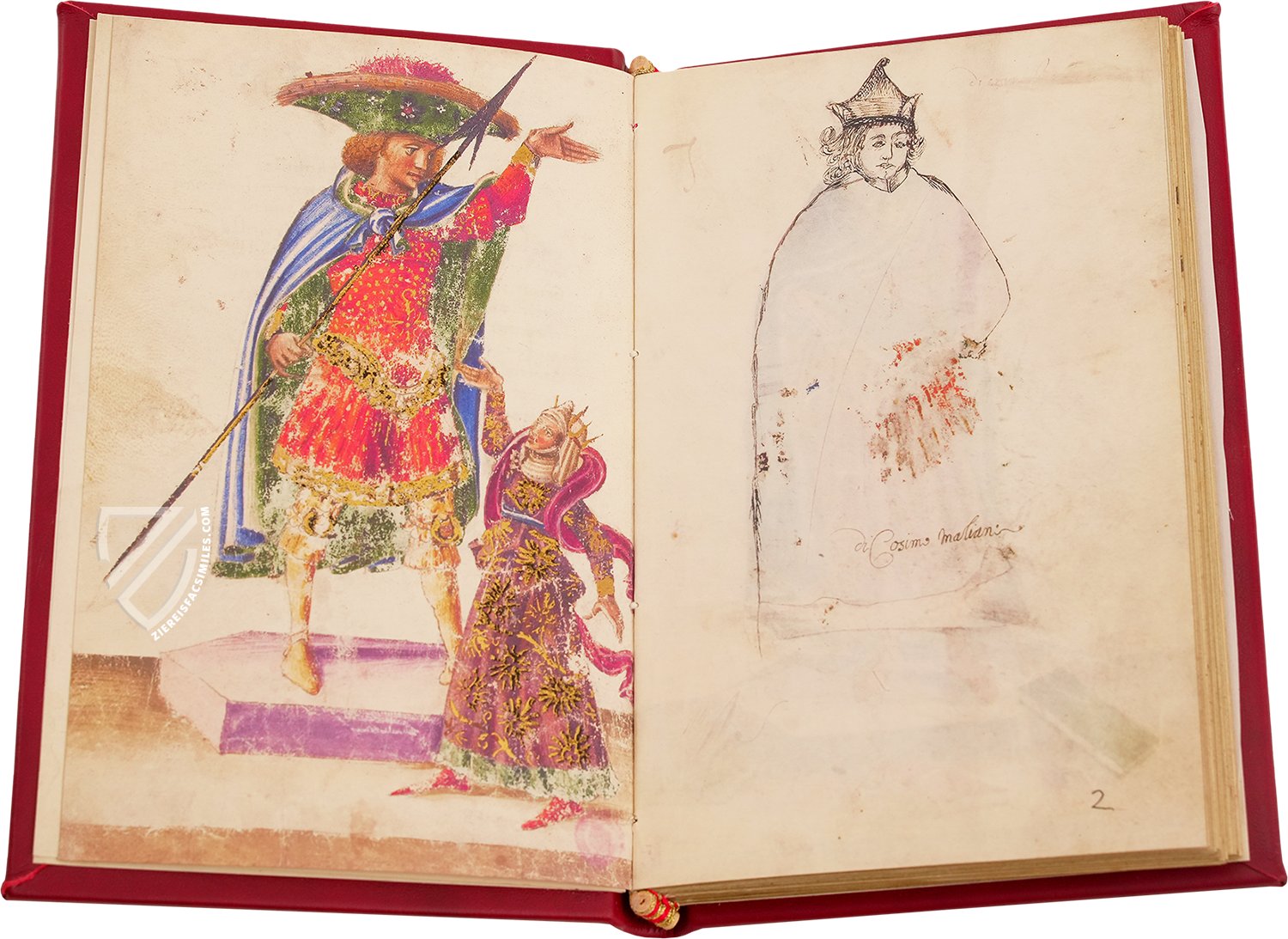

John Hawkwood: Greatest of the Condottieri

The manpower of the wealthy commercial cities was at sea, manning their great merchant fleets. As a result, they could only maintain small militias which suffered from a lack of martial spirit and were no match for feudal armies. Florence offers an example of this lack of martial spirit: of the 600 knights that the city’s upper classes supposedly provided, only 75 were proper “full-dress” knights with the rest consisting of paid replacements.

These wealthy communes saw a solution in mercenary companies, usually consisting of men from England, the Low Countries, and Germany, and led by captains called Condottieri. The word itself means “trafficker”, coming from come from condotta or “contract”, and could be applied to a merchant, but in this case, they were a Condottieri d’Armi a contractor or trafficker of armed men.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Arguably the greatest of them was named John Hawkwood, a veteran of Crécy who supposedly won his spurs (i.e. his knighthood) at Poitiers and was born in Essex ca. 1320. In 1363, he rose to become the leader of the White Company (free companies were democratic in nature and elected their own leaders), formed from among the 6,000 mercenaries who had broken off from the Great Company to take up a contract against Bernabò Visconti of Milan. Hawkwood made a reputation for himself by fighting for and against nearly every major power in Italy over the next 30 years, eventually marrying a Visconti and spending the last 15 years of his life fighting for Florence, where he was buried in the Duomo after being given an unprecedented funeral procession in a city that had once cursed him as the devil incarnate.

Chaucer Brings the Renaissance North

Born in London ca. 1343 to a wealthy family, Chaucer came to France in 1359 as part of the Hundred Years’ War acting as a courtier, diplomat, and civil servant as he had been in England. He became a member of the court of Edward III on June 20th, 1367 as a valet de chambre.

It was in this capacity that he travelled to Milan in 1368, where he came into contact with Petrarch and Jean Froissart, a French-speaking author of chivalric literature and court historian. He may have become acquainted with John Hawkwood during this visit as well, but certainly would have come into contact with him during his second and third Italian expeditions in 1372 and 1378. It is believed that John Hawkwoodwas the inspiration for Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale. It was then that he came into contact Boccaccio, whose works served as an inspiration for his own along with those of Dante and Petrarch.

Chaucer became devoted to the translation of their works and to adapting them. His famous Canterbury Tales are an adaption of the Decameron that, along with other works, did for English what these three authors had done for Italian. This contributed significantly to the rise of English during the Late Middle Ages. Together with the theologian/philosophers William of Ockham and John Wycliffe, Geoffrey Chaucer laid the foundations for the coming Renaissance in England along with helping to define not only a language for the English nation but a sense of identity as well.

Experience more