PAINTED PICTURE FRAMES – FROM FOLIATE BORDERS AND FRAMING ARCHITECTURES TO A GLIMPSE INTO ANOTHER SPHERE

Framings have been part of medieval book illumination from the very beginning. They enclose miniatures and sometimes also text pages, define pictorial compartments and spaces and serve as additional decoration. They are also repeatedly and artfully used as structuring elements to add further layers of meaning to images or to support complex pictorial narratives. As wide borders, they often became infinite spaces of figurative depictions themselves in the late Middle Ages. With this blog post, we would like to give you a broad and informative impression of the overwhelming and artistic wealth of forms of illuminated framings and their diverse designs: Ornamental picture frames, windows into another dimension, entire landscapes in the smallest of spaces or the artistic deception of the eye... Now enjoy browsing!

Framing Images: Picture Frames on Parchment

Subtle picture frames, reminiscent of physical wooden frames for panel paintings, run through all stylistic periods of book illumination. With shadings and white heightenings along with thoughtfully placed lines, they create a three-dimensional effect.

To the facsimile

Often several differently colored frame strips were combined into one framing, as in Diego Homen's atlas 1561. The miniature of the Flagellation of Christ in the Rosary Psalter of Joanna of Castile, on the other hand, offers a wonderful example of the reproduction of woodcarving, which was also found in contemporary wooden picture frames that were often also gilded.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

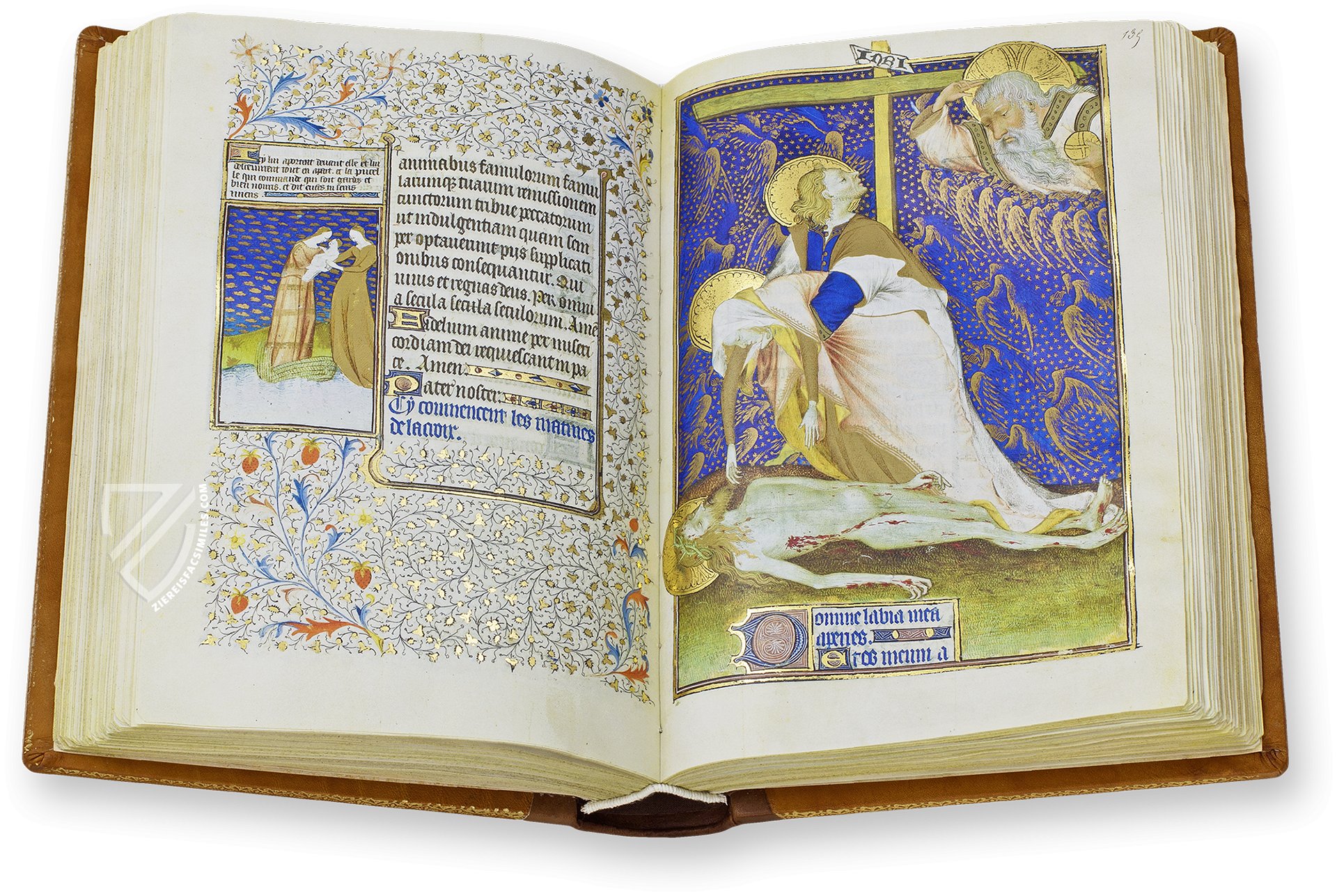

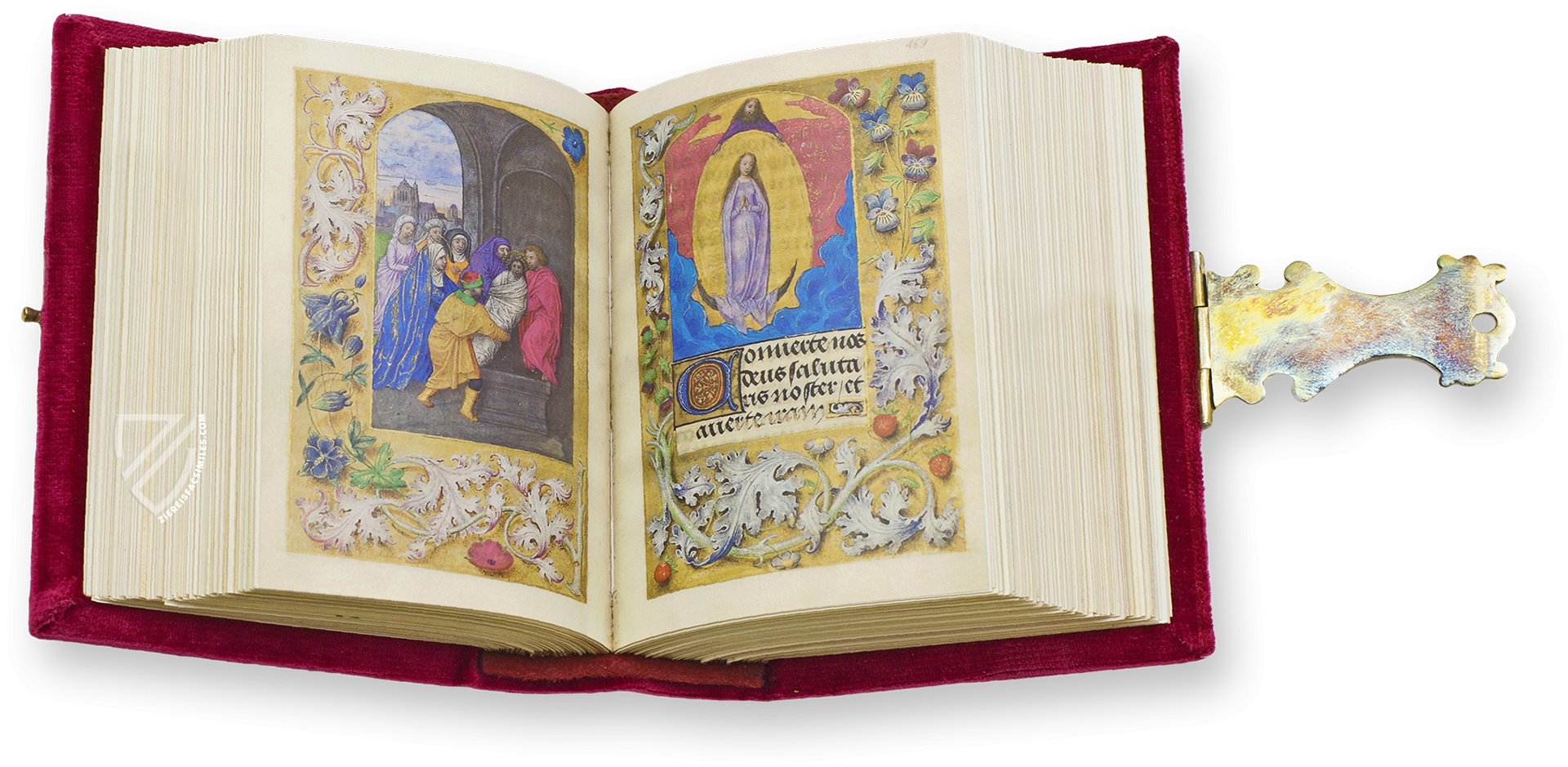

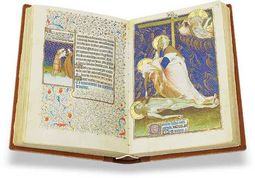

Golden framing strips can be found again and again in illuminated manuscripts, even without such filigree details. The Lamentation of Christ in the Rohan Hours impressively demonstrates that the treatment of such framings was very free and could bestow images with additional layers of meaning. Here, the framing strips define the visible pictorial space, but are intersected in three places. It is no coincidence that the cross, God the Father and the deceased Christ protrude beyond the framing: while the mourning Mary and John remain attached to the earthly sphere in the pictorial space, Christ and God the Father with their divine nature belong to the invisible heavenly realm.

In other cases, illuminators also liked to adapt the framing strips to the content of their illumination, emphasizing specific features such as special shapes or the size of objects and figures. The result are unique frame formats that immediately catch the eye.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

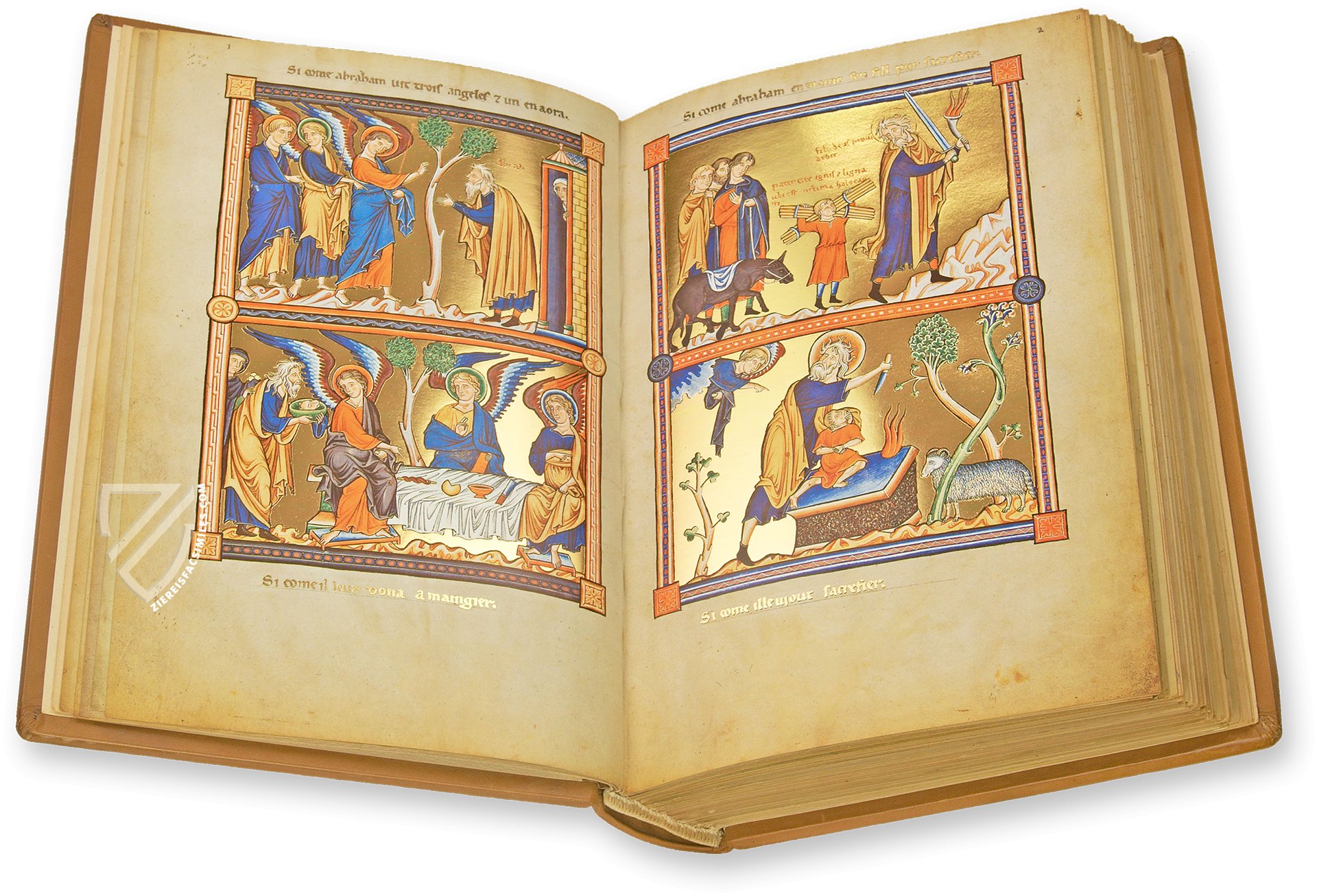

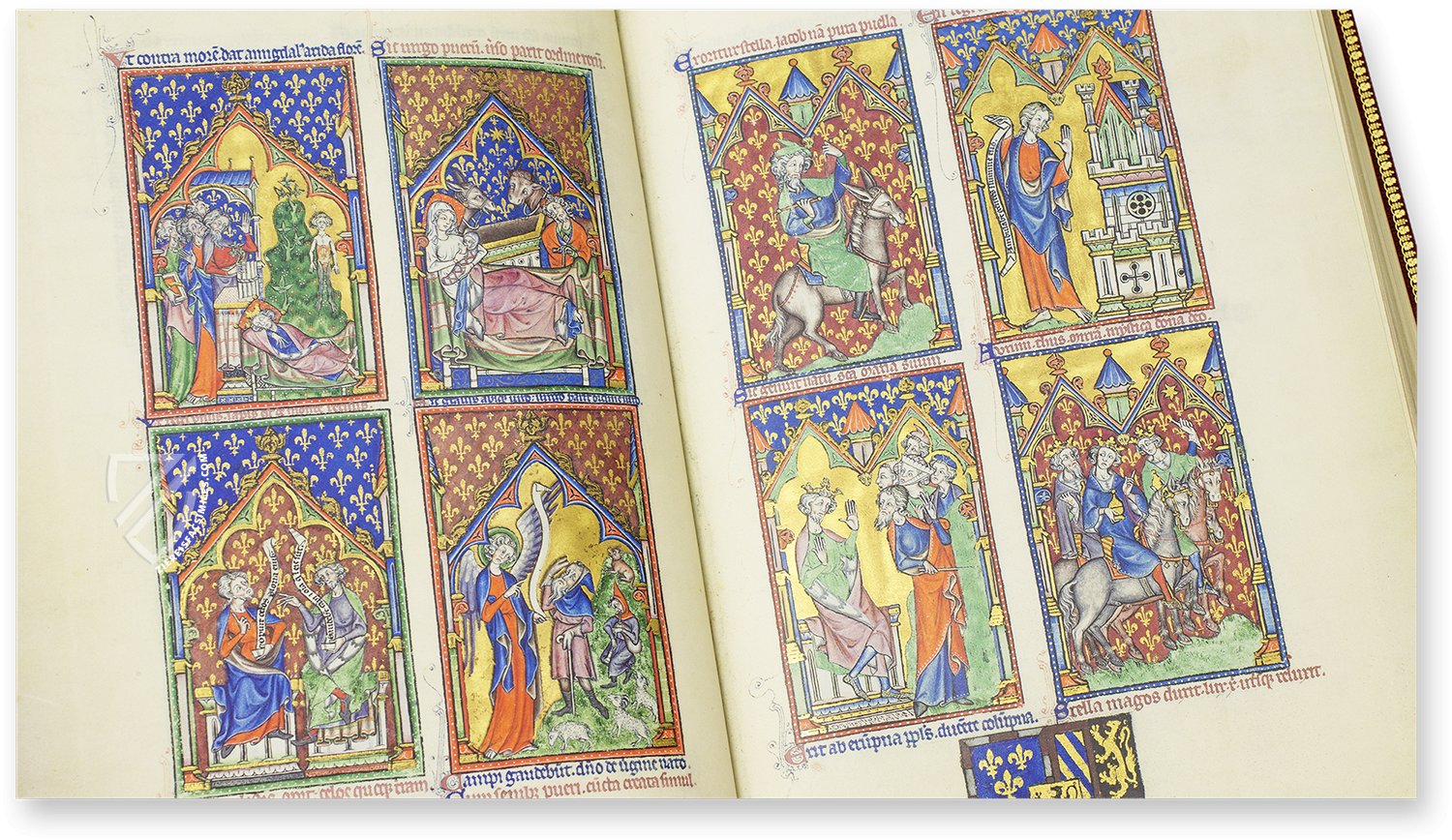

Sometimes, however, the framings determined the special picture formats. In calendars in particular, the Labours of the Months and zodiacal signs are often found in medallions, quadrilobed framings or composite ones consisting of various geometric shapes, such as in the Belles Heures of Jean Duke of Berry. A particularly impressive and famous example of a picture program primarily consisting of medallions is the imposing Picture Bible of Saint Louis.

Framing Ornaments: Beyond Mere Decoration

To the facsimile

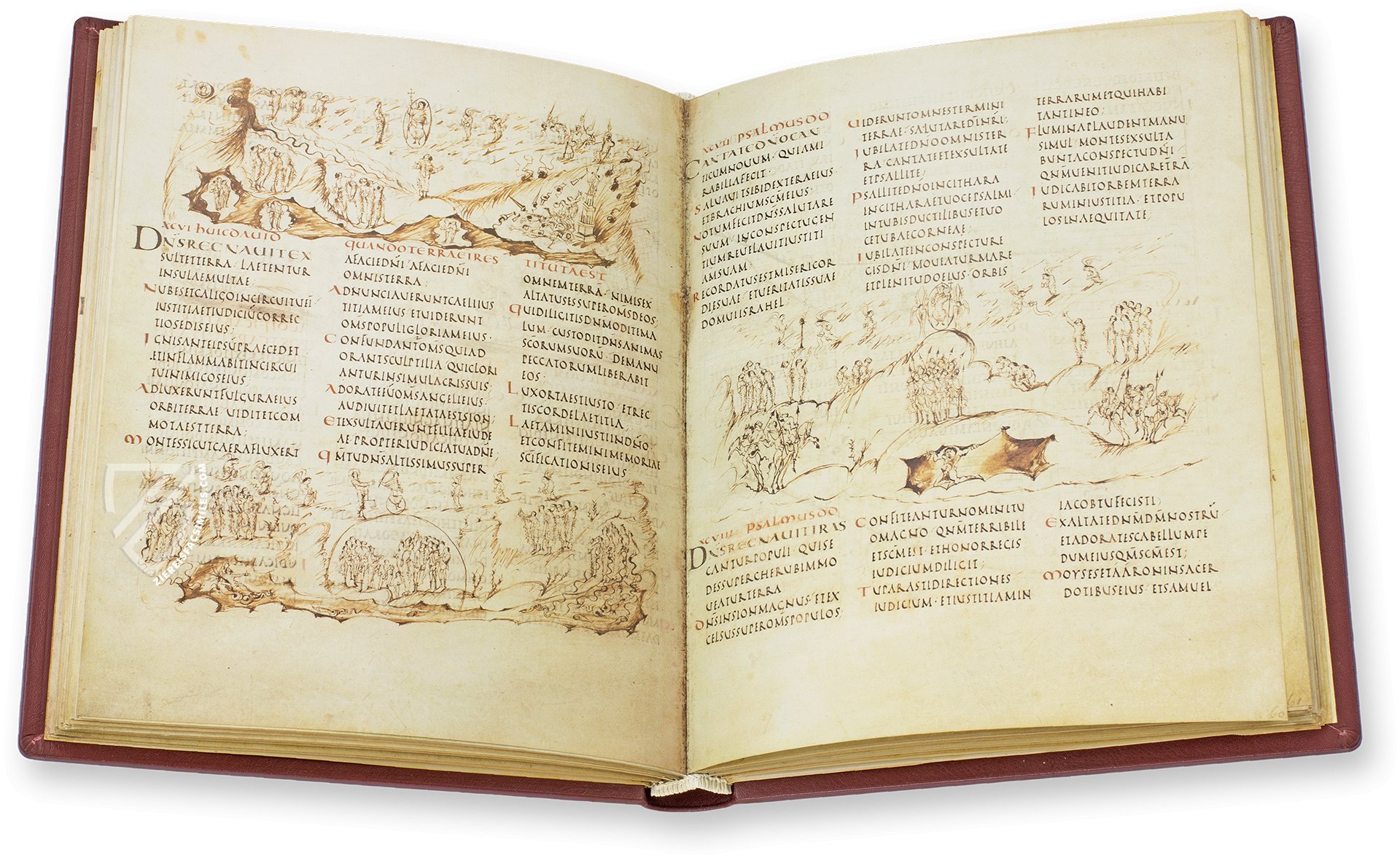

Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, however, illuminators also enjoyed creating framings of decorated borders with an almost infinite variation of ornaments. They were inspired by ancient and medieval models on the one hand, but also constantly created new designs based on geometric, floral, vegetal and linear forms. Thus, narrow, supposedly simple framing strips often became decorative pictorial elements.

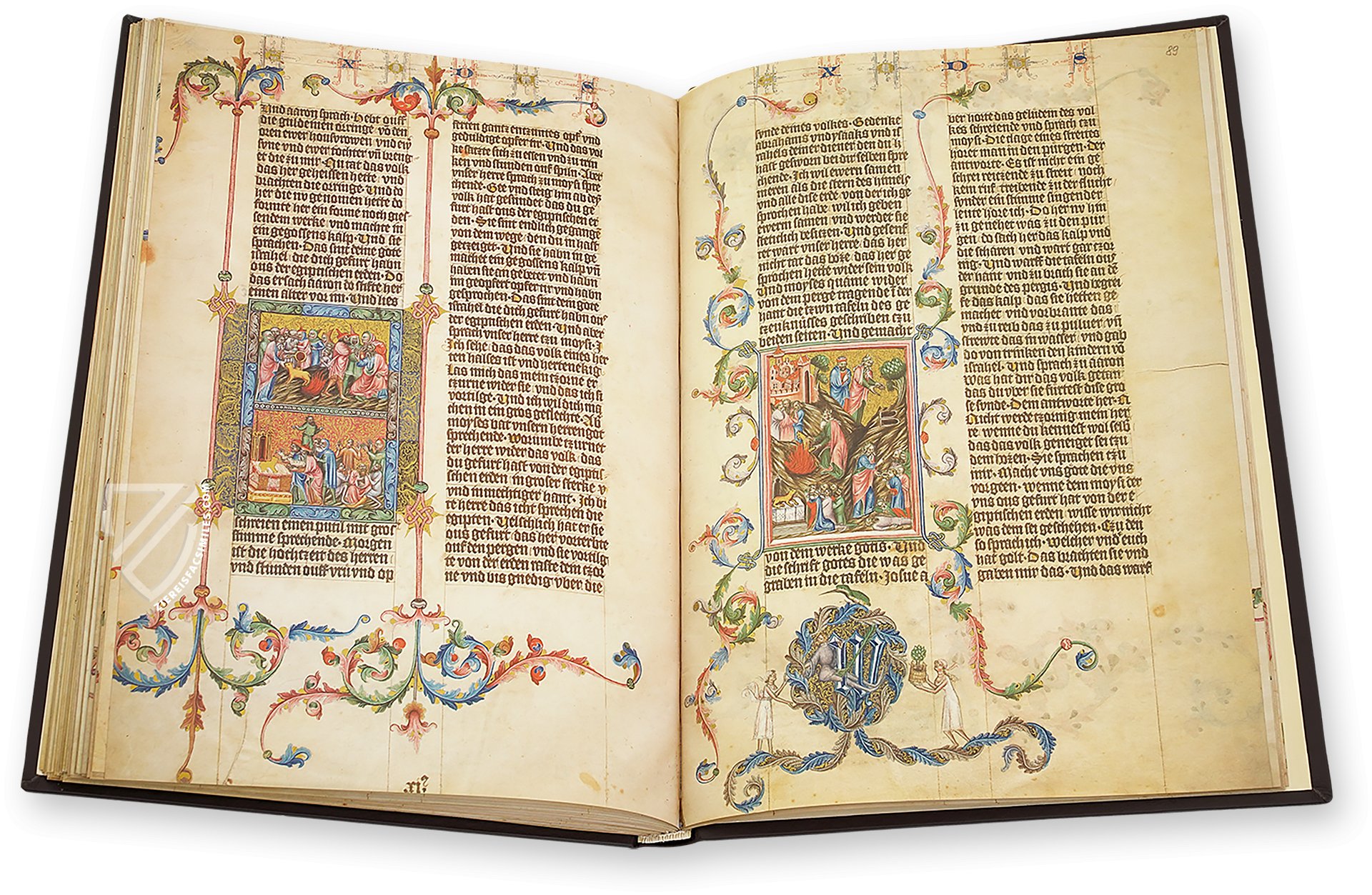

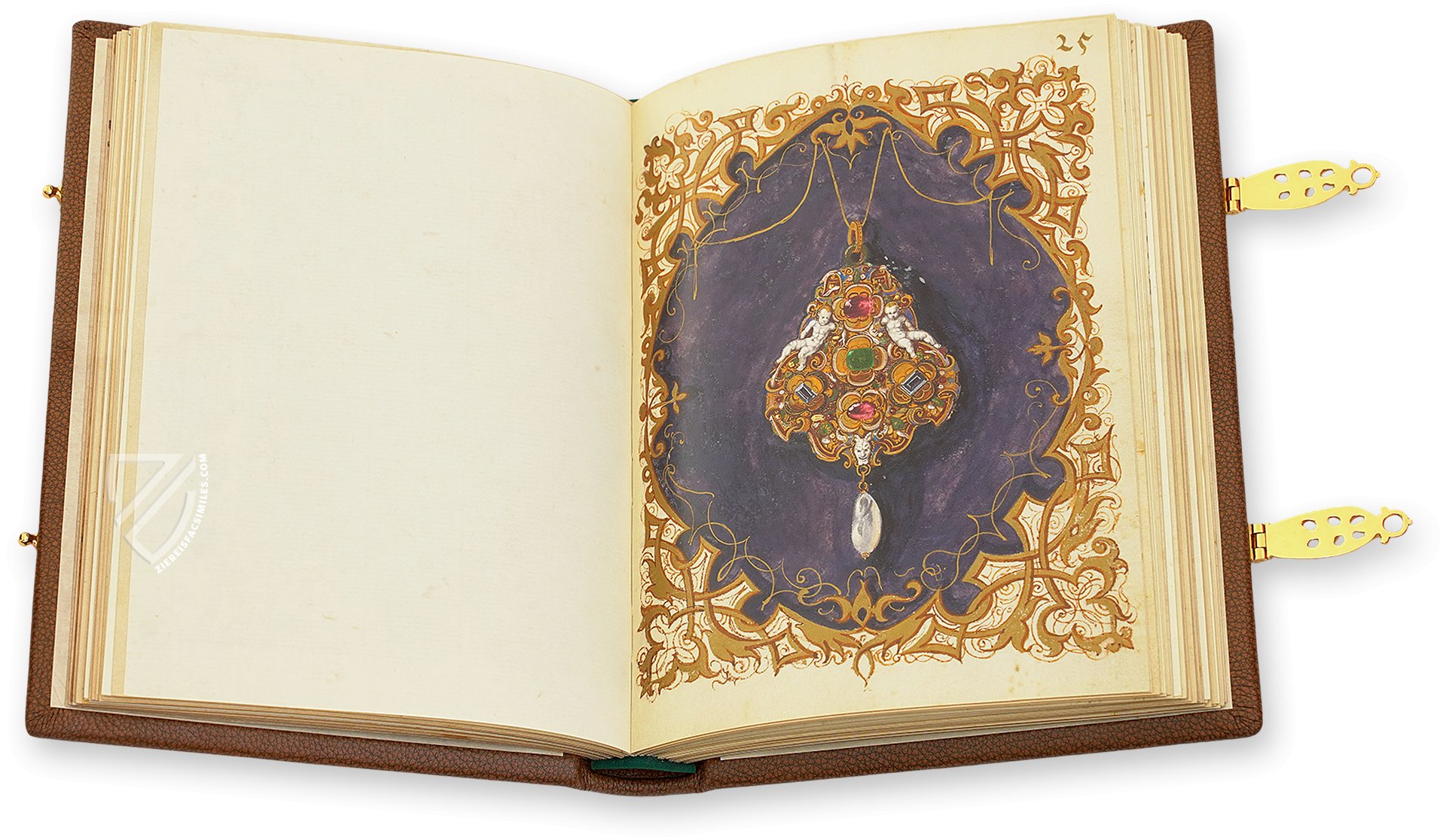

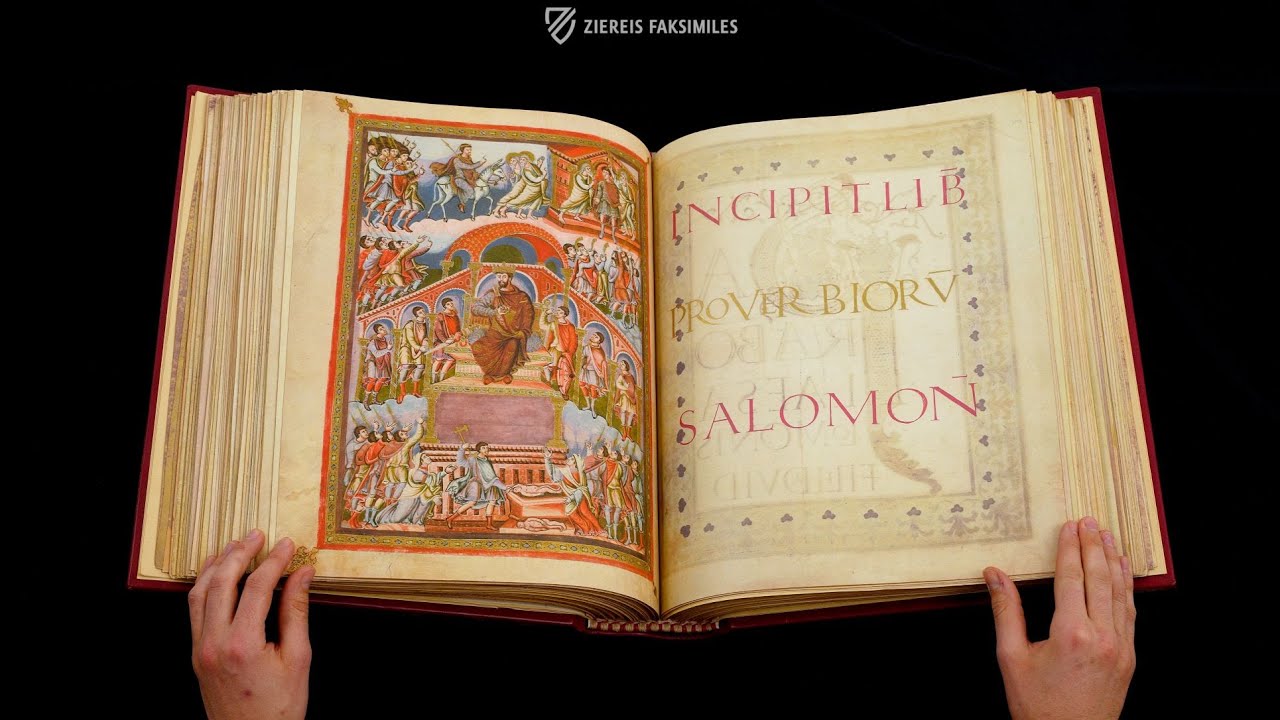

In particularly splendid luxury manuscripts, there were no limits to the opulence of such ornamental framings. Text and picture pages could be artfully accentuated by gold-decorated, wide frames made of the finest ornaments.

Opulent framings for magnificent, gold-decorated codices

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

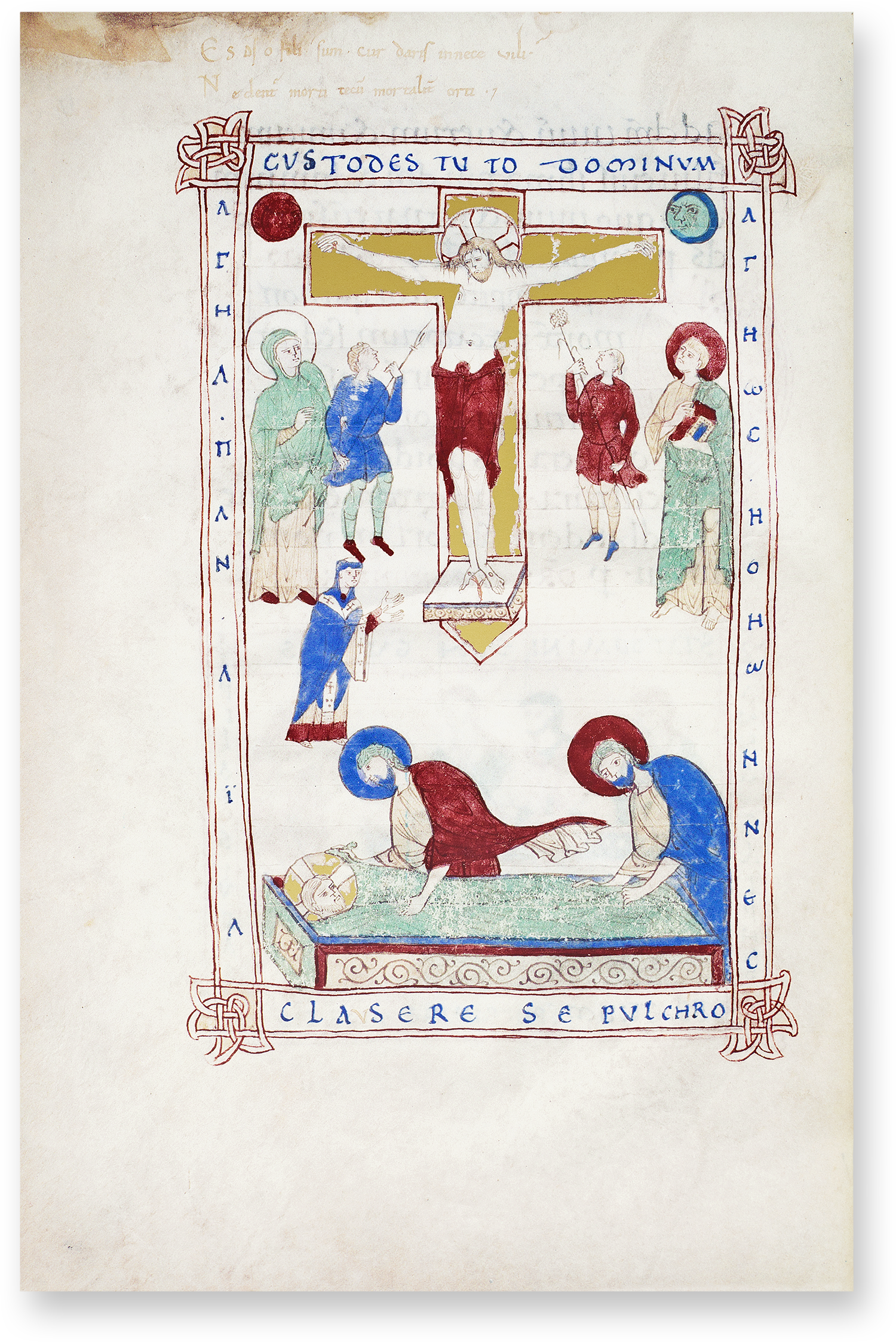

Framing Letters: Scripture as Picture Frames

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

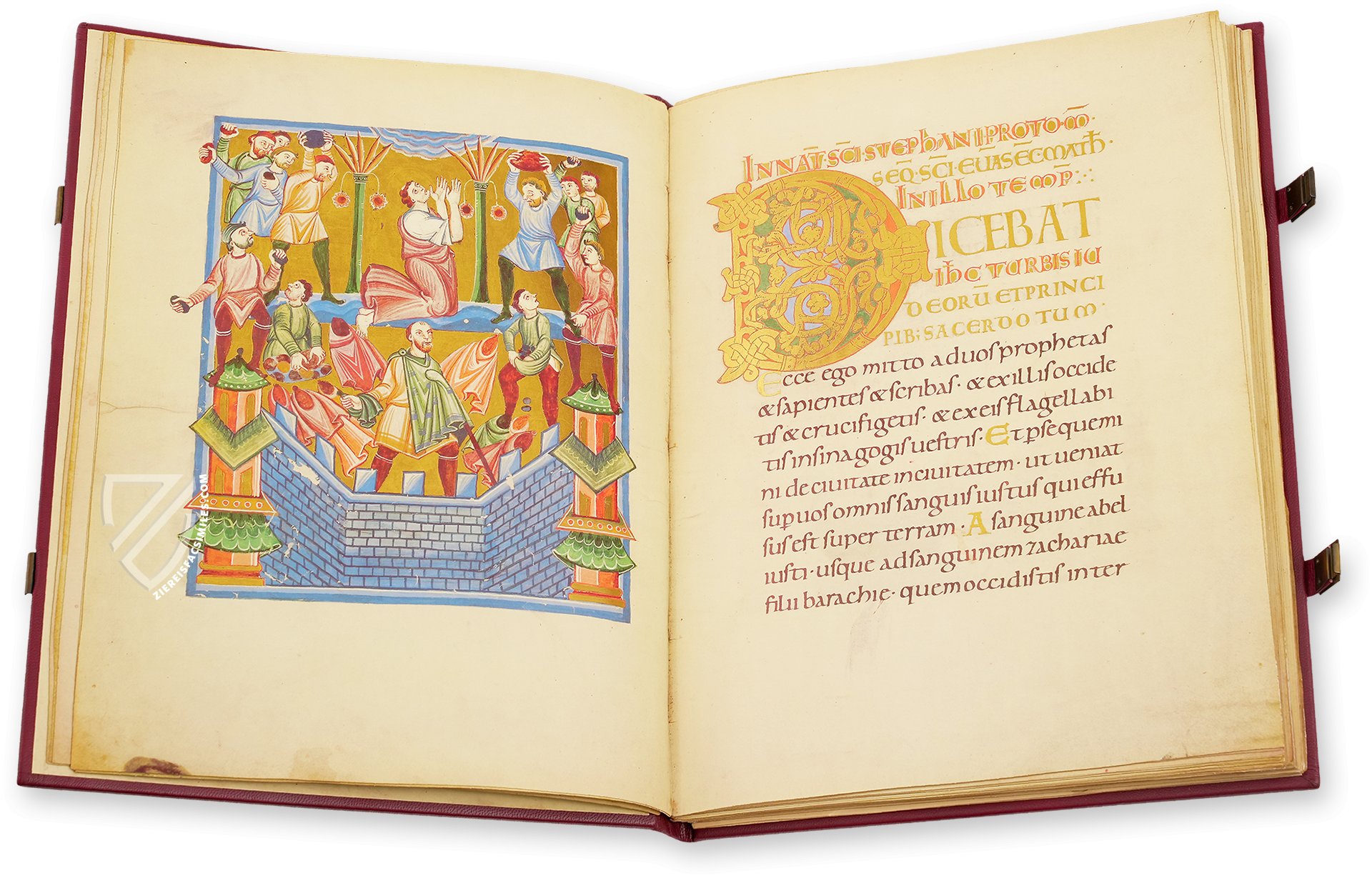

The decorated borders framing miniatures could equally well be filled with text, providing the viewer with additional information and layers of meaning. In the case of the Sacramentary of Warmund, the surrounding text is combined with interlace corners.

Framings were applied with lettering throughout the Middle Ages

Narrow Doors and Tiny Windows: Passages into Another Dimension

Doors, windows and archways are always an interesting element of medieval art. They help the viewer to understand the spatial systems, time levels and narratives depicted. There are diverse examples of this type of playful artifice, not only in book illumination.

To the facsimile

In the miniature of the Washing of Christ's Feet by the sinner Mary Magdalene in the St. Alban's Psalter, the opening in the frame is used to emphasize the ointment jar in the servant's hand outside the picture space. And indeed, a further temporal level is introduced here: Mary Magdalene is about to dry Jesus' feet with her hair. According to the Gospel of Luke, she will only anoint his feet in the next step. This future action, which will lead to the acquittal of her sins, is artfully depicted here.

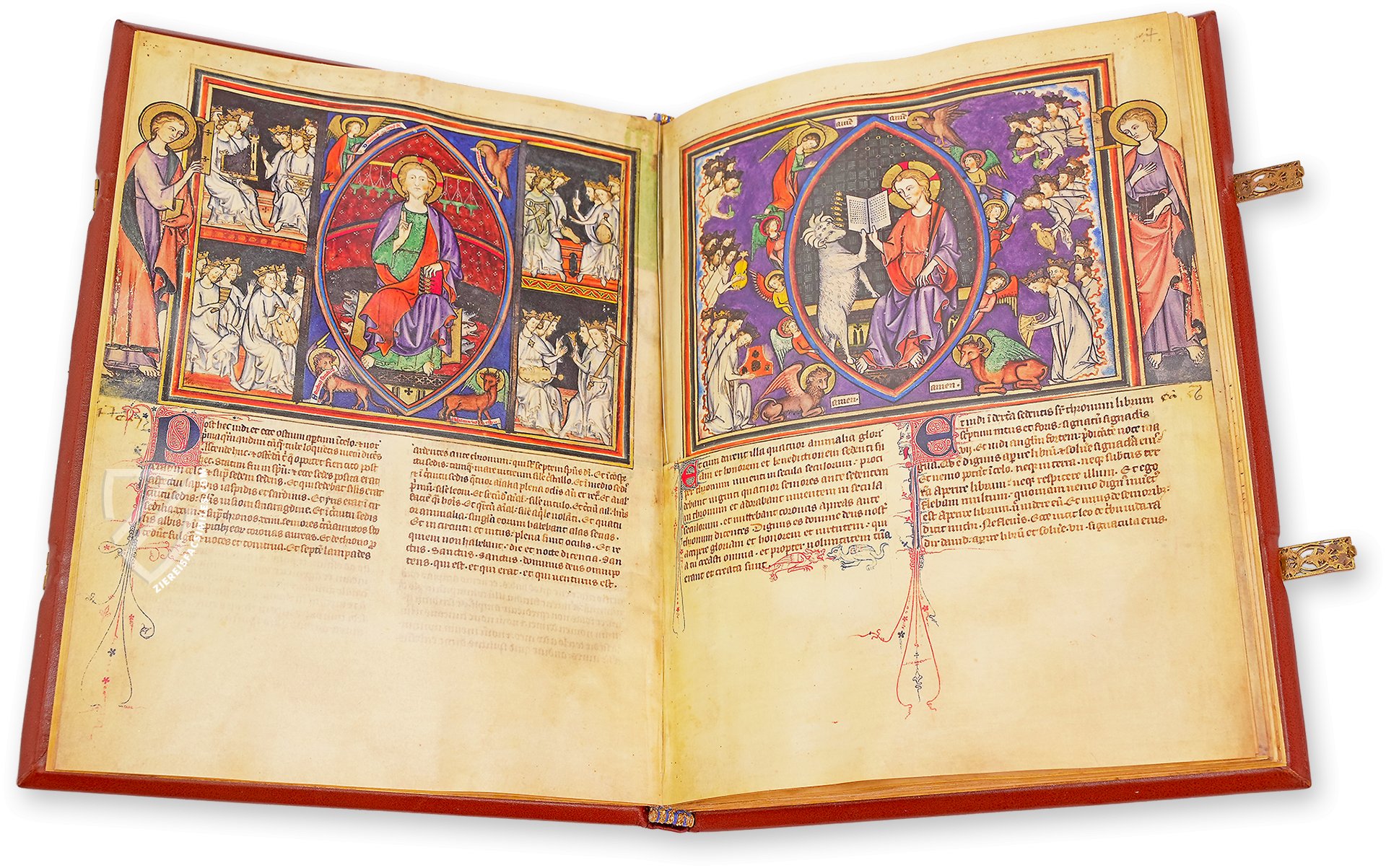

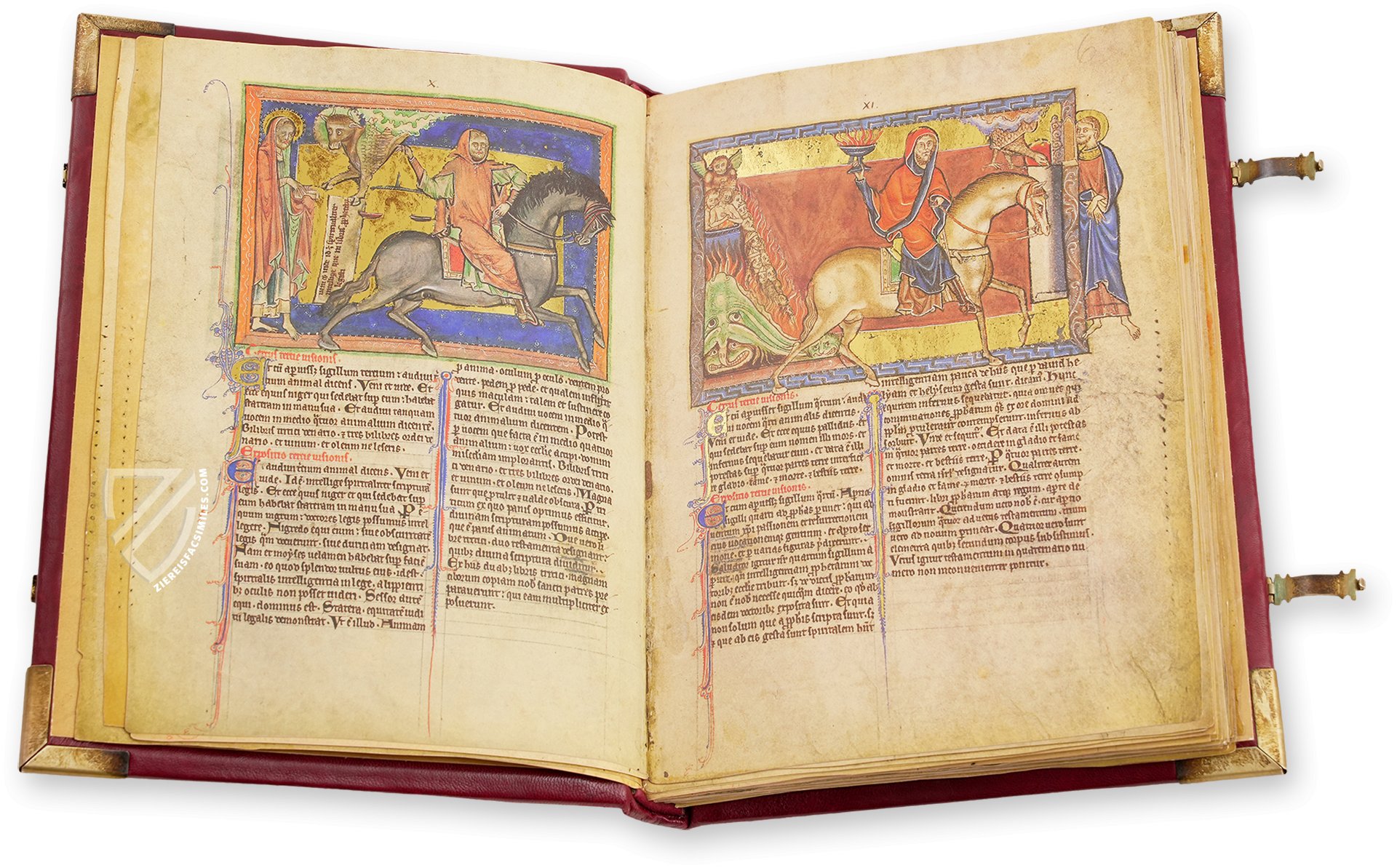

In Apocalypse manuscripts such as the Apocalypse of Lambeth Palace and the Cloisters Apocalypse, tiny windows in the framings serve to elucidate the visionary character of the Revelation of John. The saint's view of the future events at the end of time from the outside is transferred to the pictorial level in an comprehensible way. John does not appear as part of his vision, but as an eyewitness to the prophecy of salvation history. This also reinforces the authenticity and authority of his subsequent text, the last book of the New Testament.

To the facsimile

Multi-layered Framing Programs: Sophisticated Depictions in the Smallest of Spaces

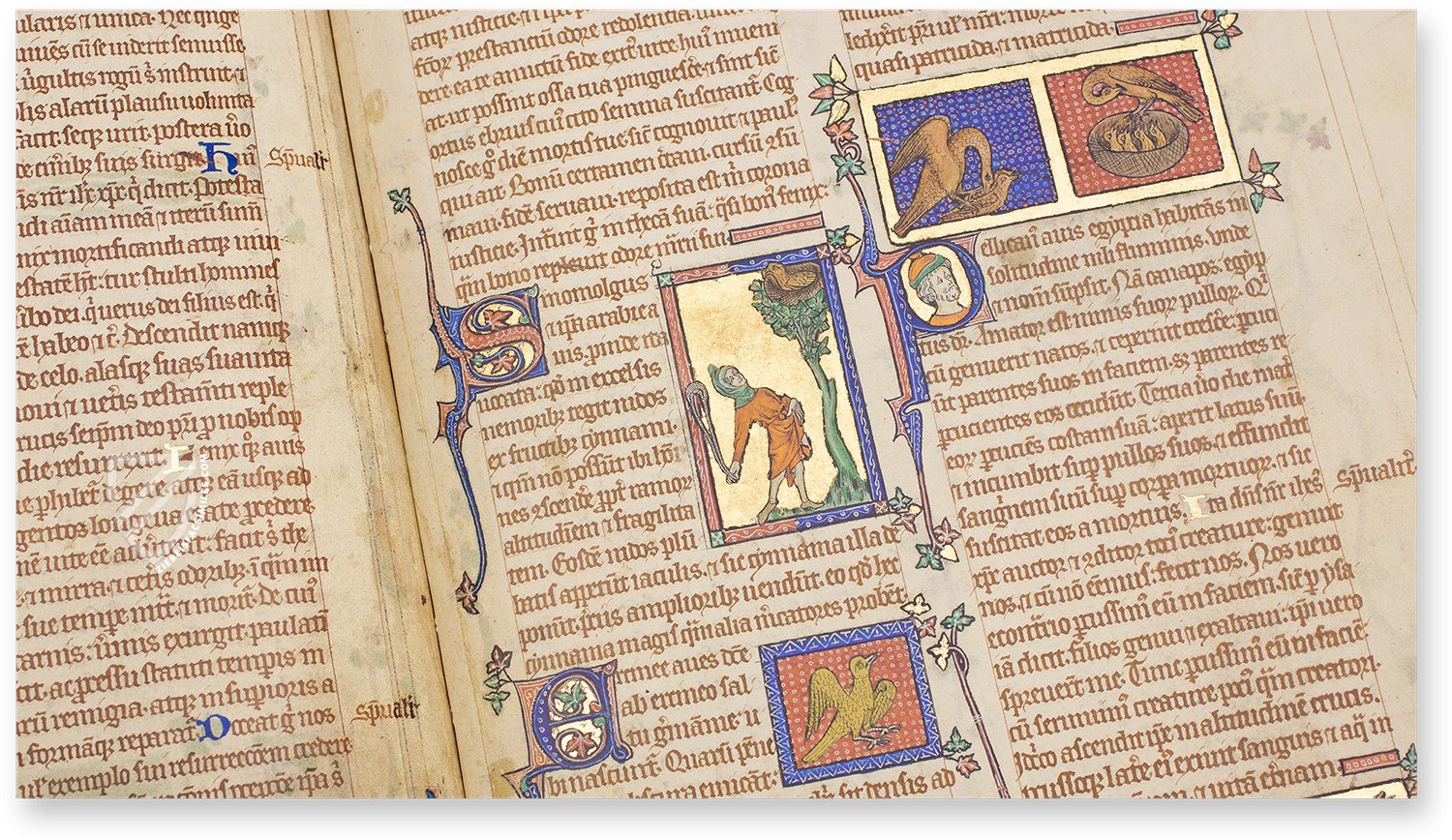

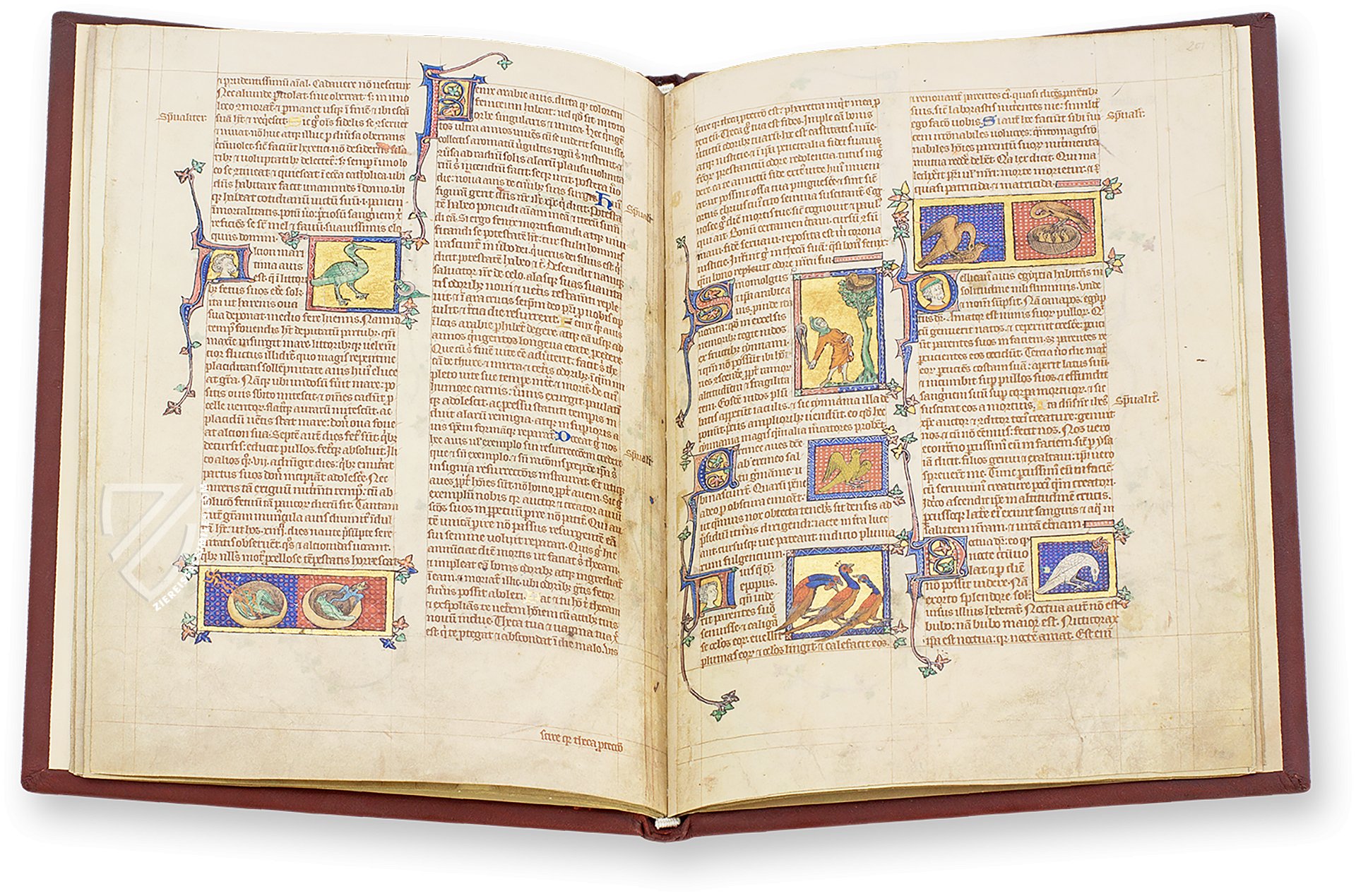

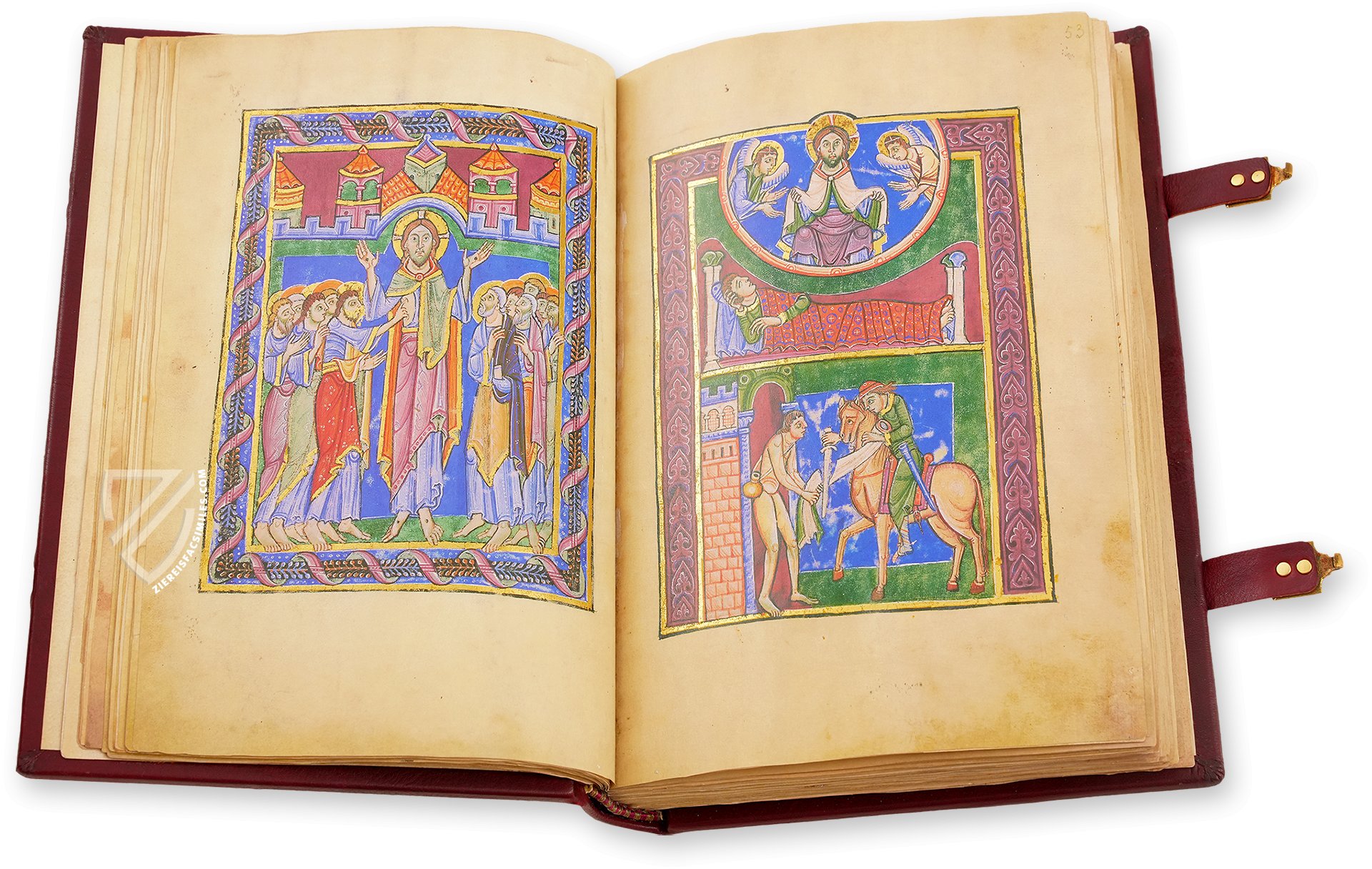

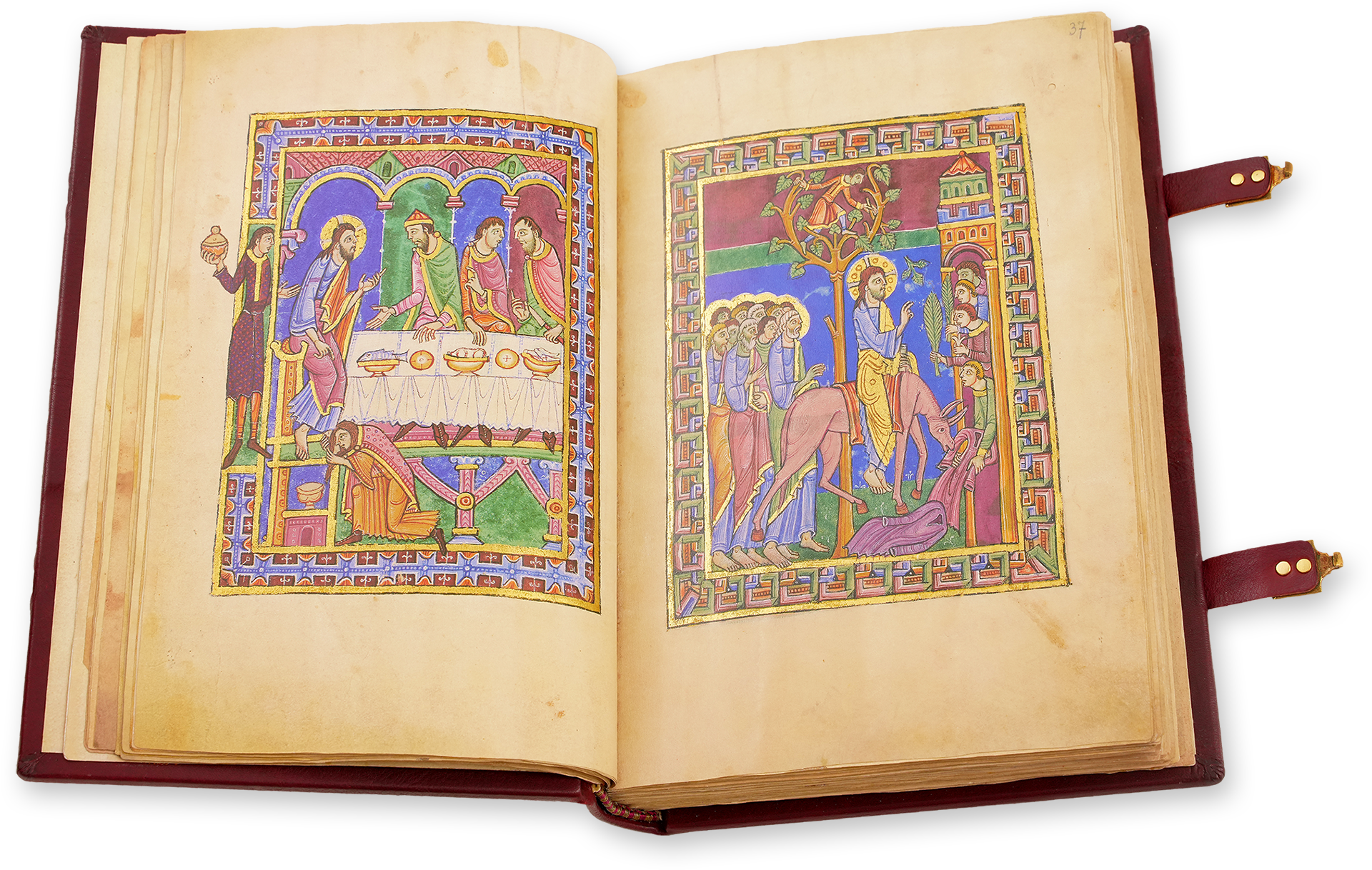

In many medieval manuscripts, we are confronted with multi-layered, complex framings that go beyond the outer framing of a miniature. Rather, further pictorial compartments are differentiated within a surrounding frame by various other internal framings.

Complex frame and picture programs were usually based on a sophisticated theological concept

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

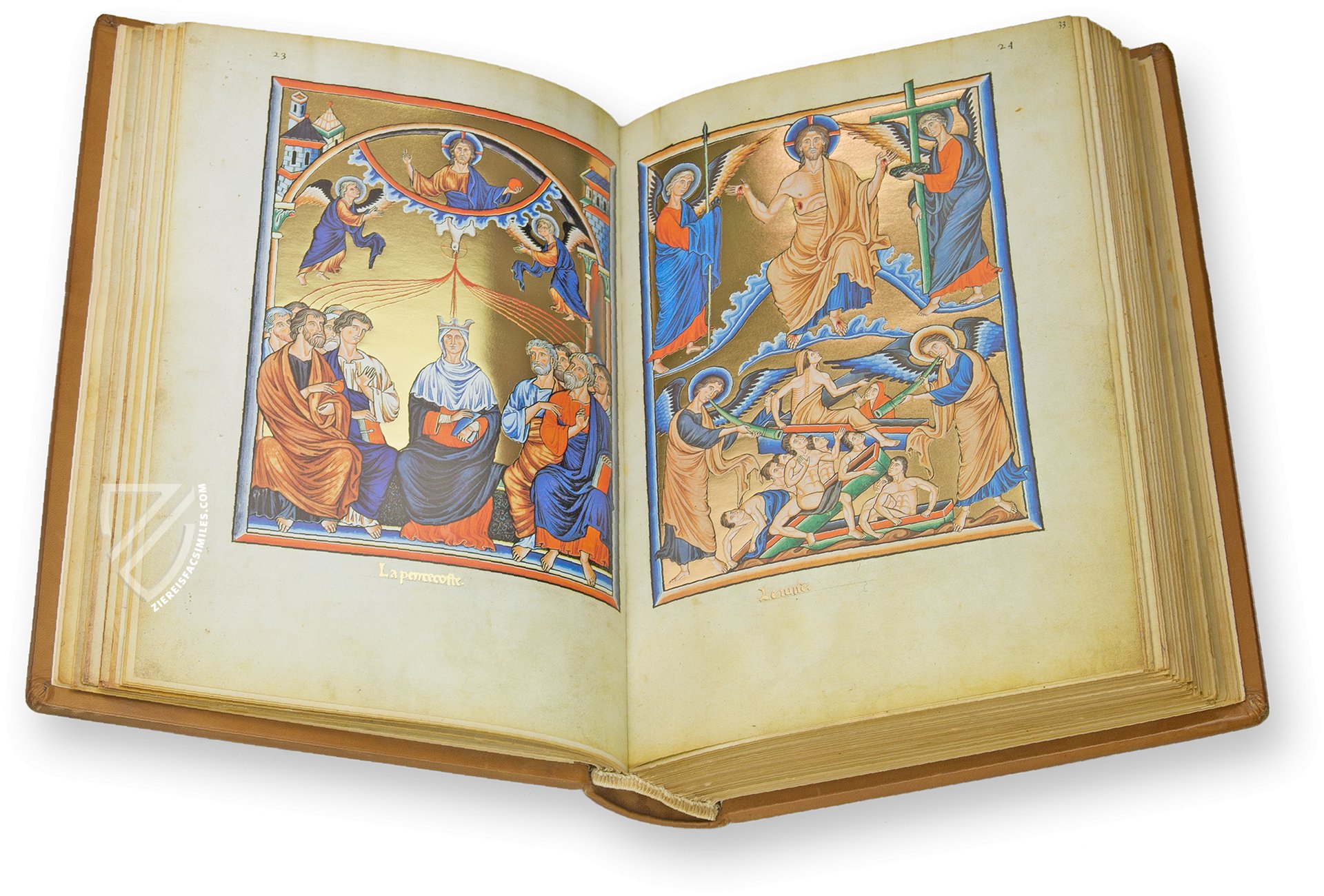

This often concerns symbolically charged iconographies of Christ, such as the Maiestas Domini - seen here in the Bible of St. Paul Outside the Walls and in the Speyer Pericopes. The double framing in the Peterborough Psalter in Brussels, on the other hand, was more of an aesthetic and structural decision. In other cases, multi-layered framing systems can serve to differentiate between spatial and temporal levels.

Little Space for Plenty of Creativity: Marginal Pictorial Spaces as Areas of Great Artistry

To the facsimile

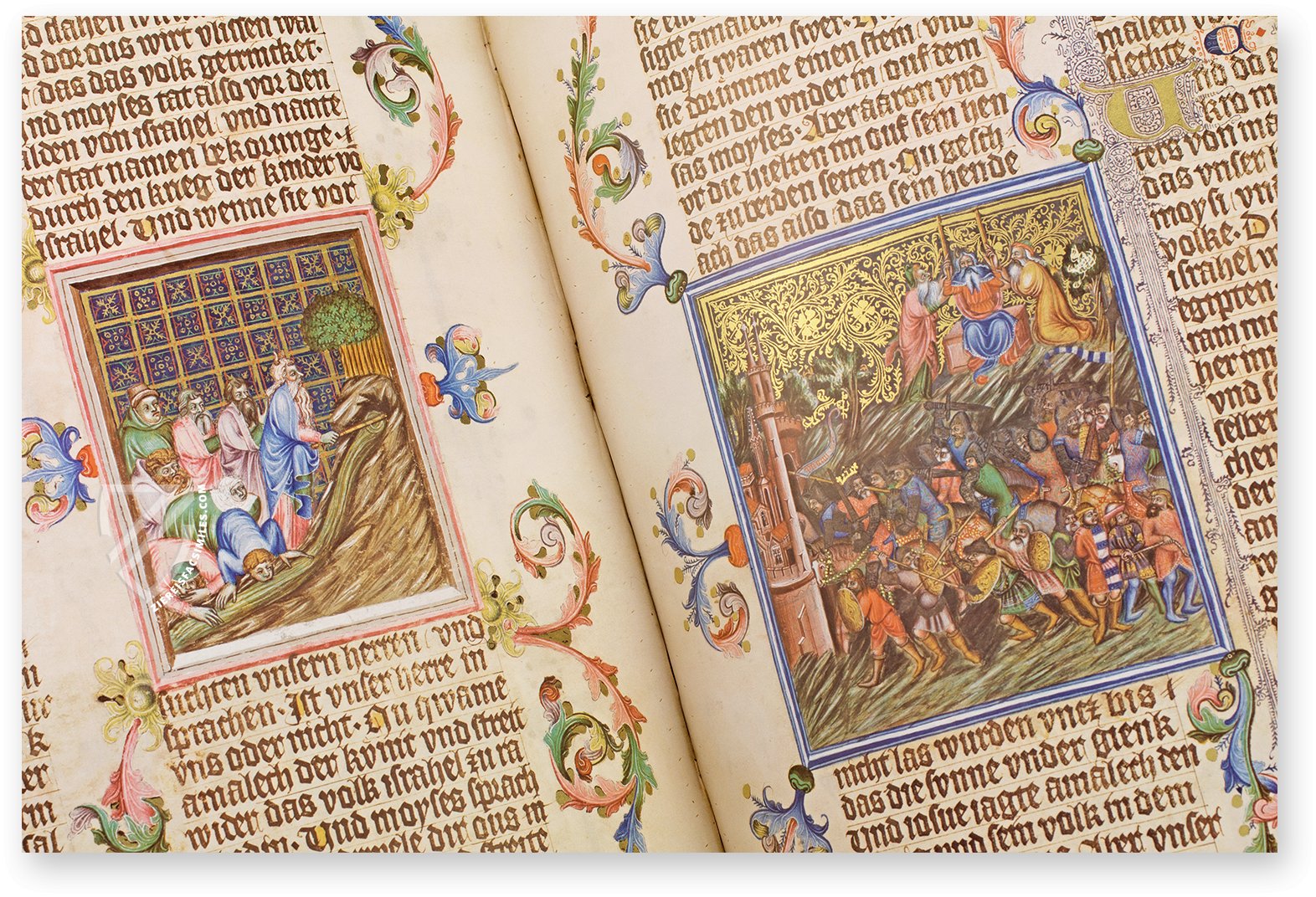

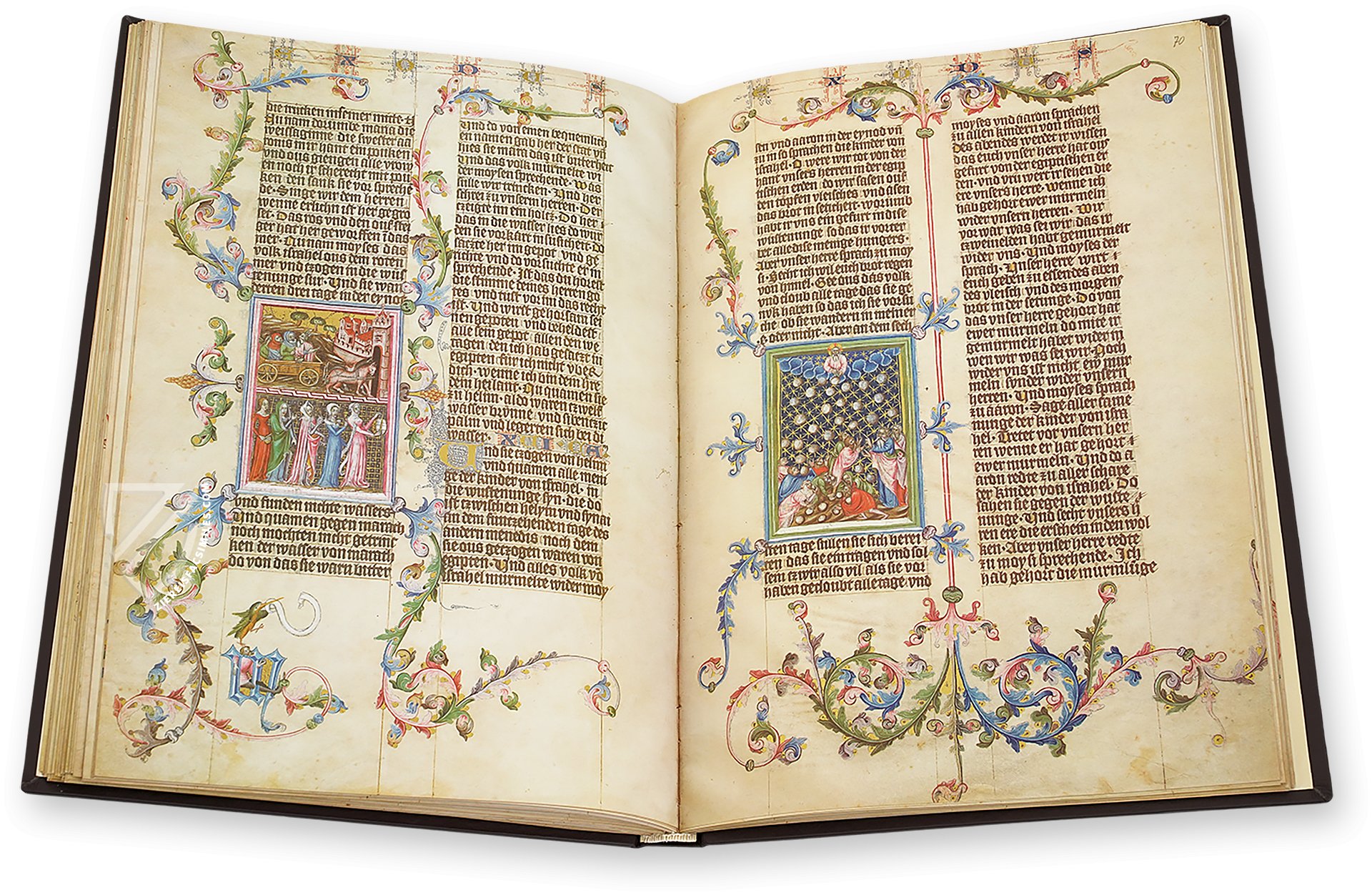

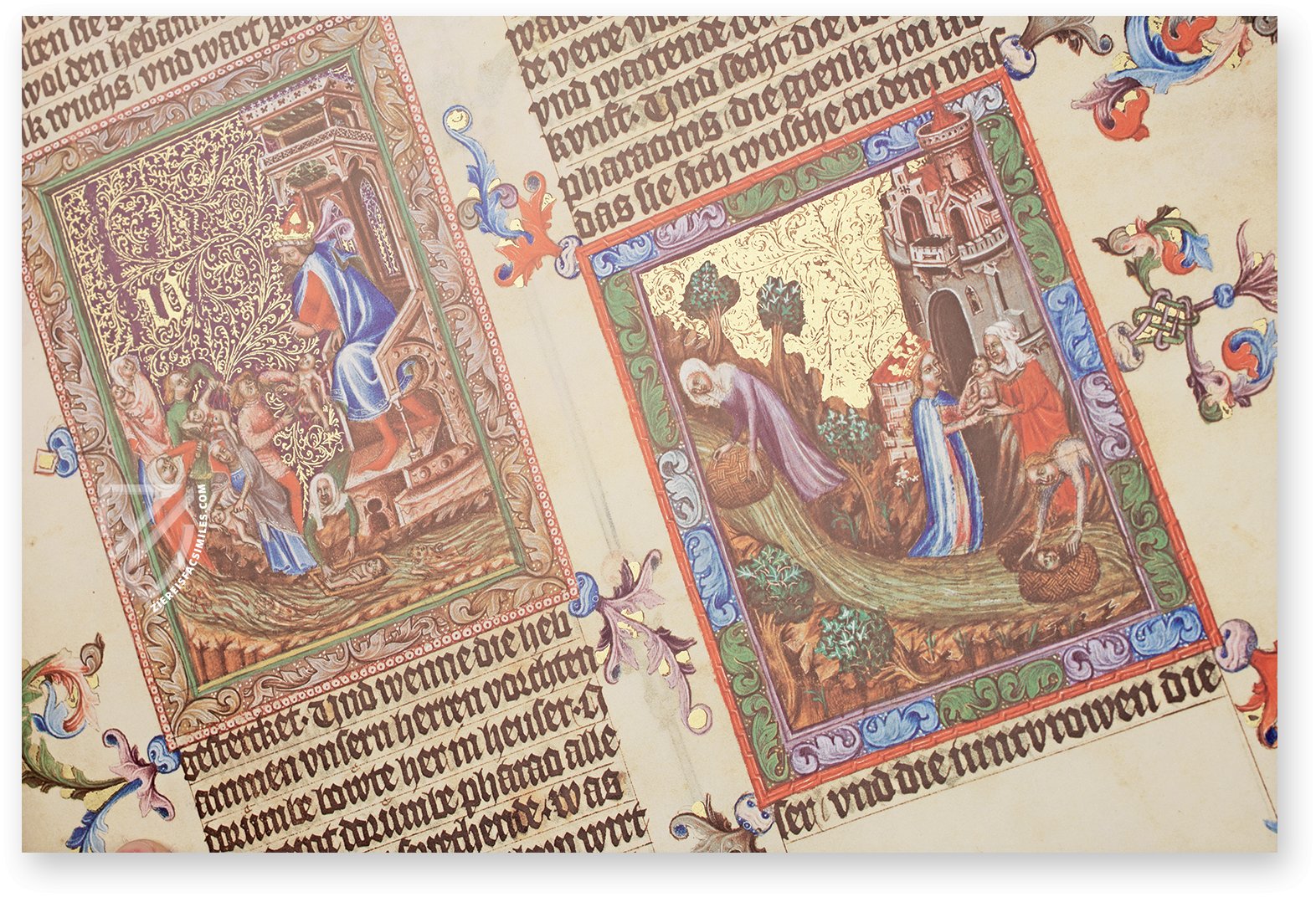

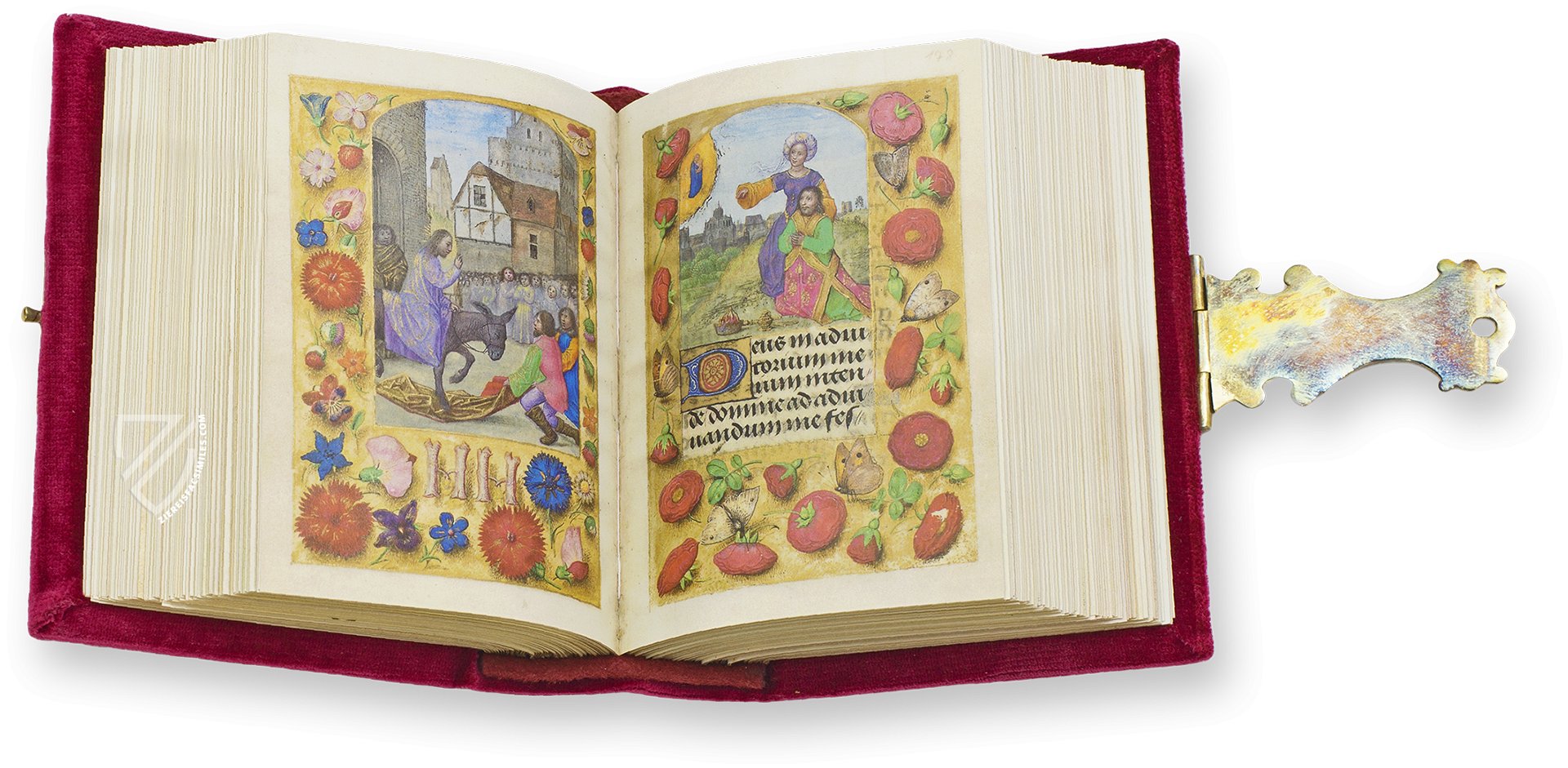

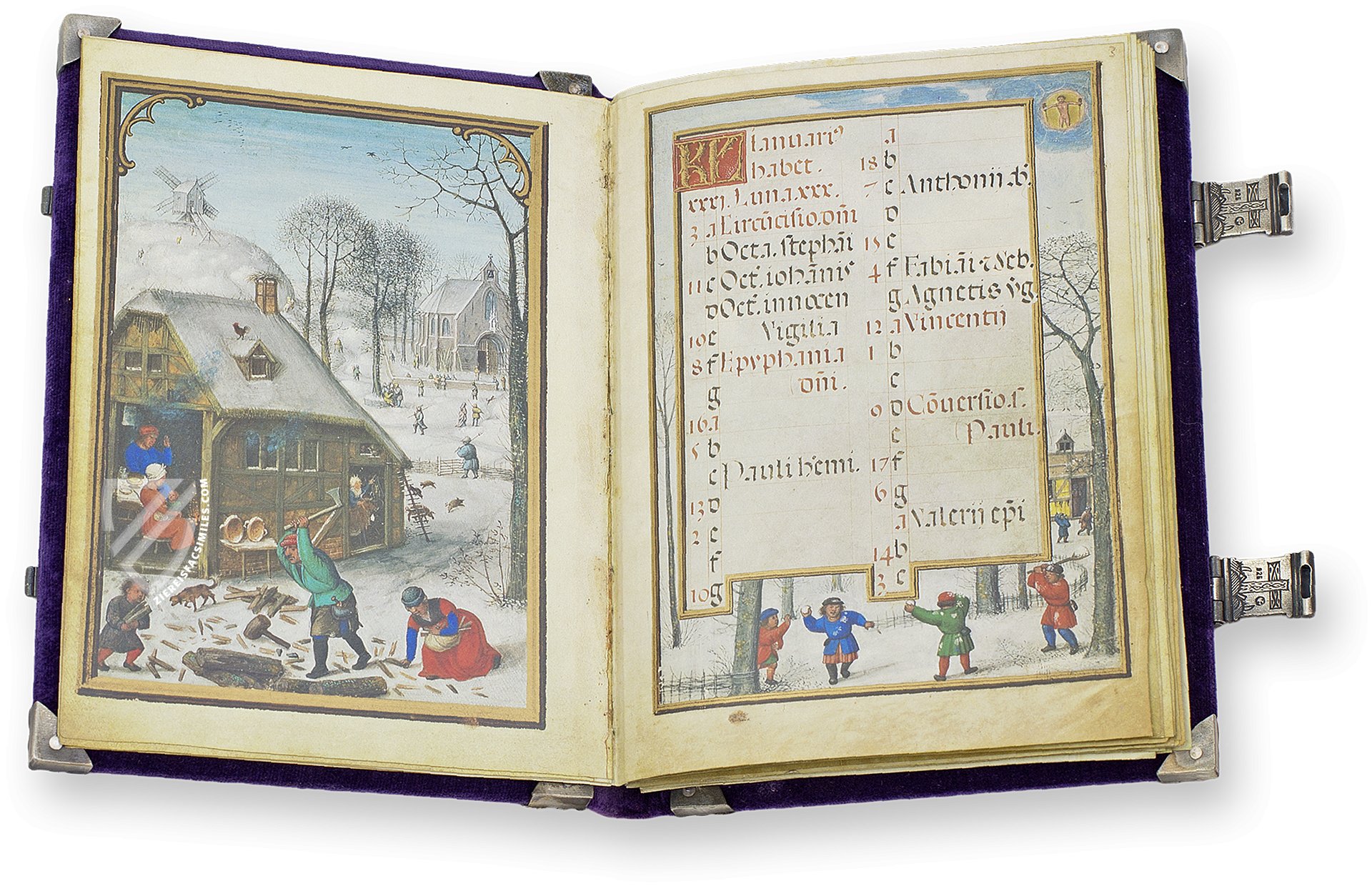

In the Gothic period, simple decorated borders were joined by a wide variety of foliate borders, which usually surround not only miniatures but entire pages. From the filigree vine and ivy leaf scrolls that either grow subtly around the pages, such as in the Turin-Milan Hours, or almost completely occupy the margins of the Belles Heures of Jean Duke of Berry in a consistent, lavish perfection.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The variety of shapes of the foliate borders was almost limitless - from stylized filigree to naturalistic foliage

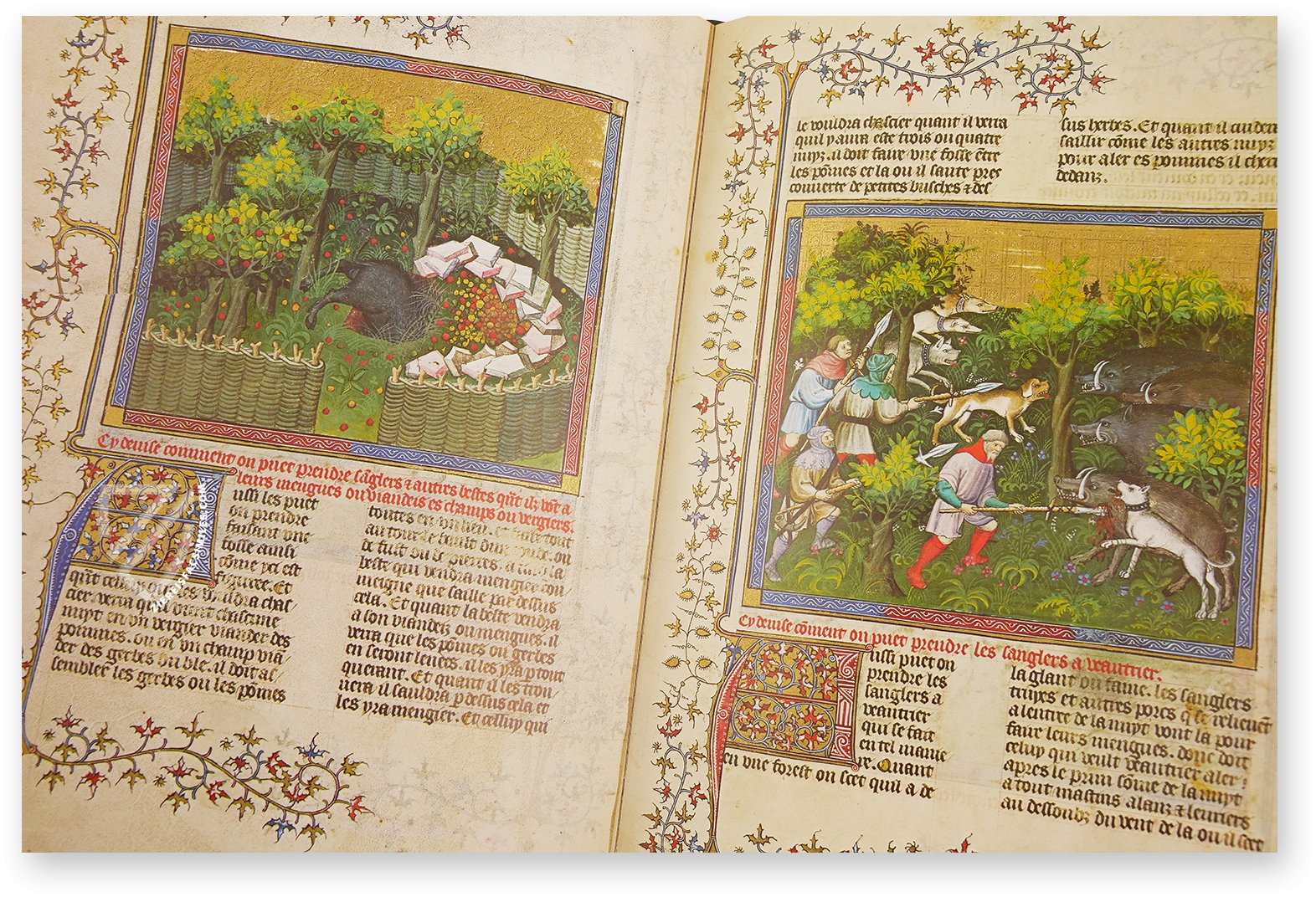

However, the leaves of the vines could also take on larger, vegetal forms and sometimes incorporate plants, flowers and fruit in an almost naturalistic way, as the beautiful page from the Book of Hours of Rouen demonstrates.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

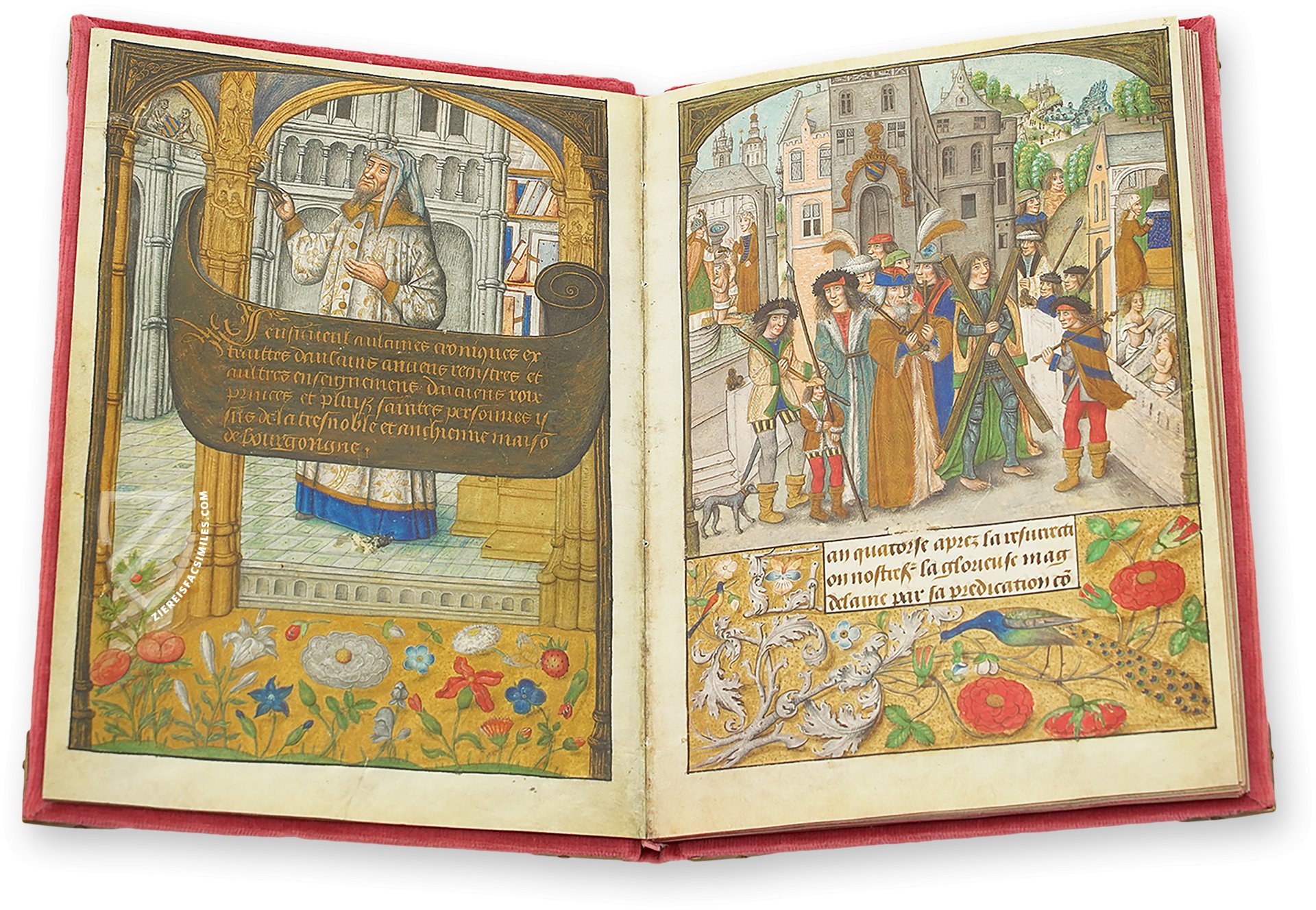

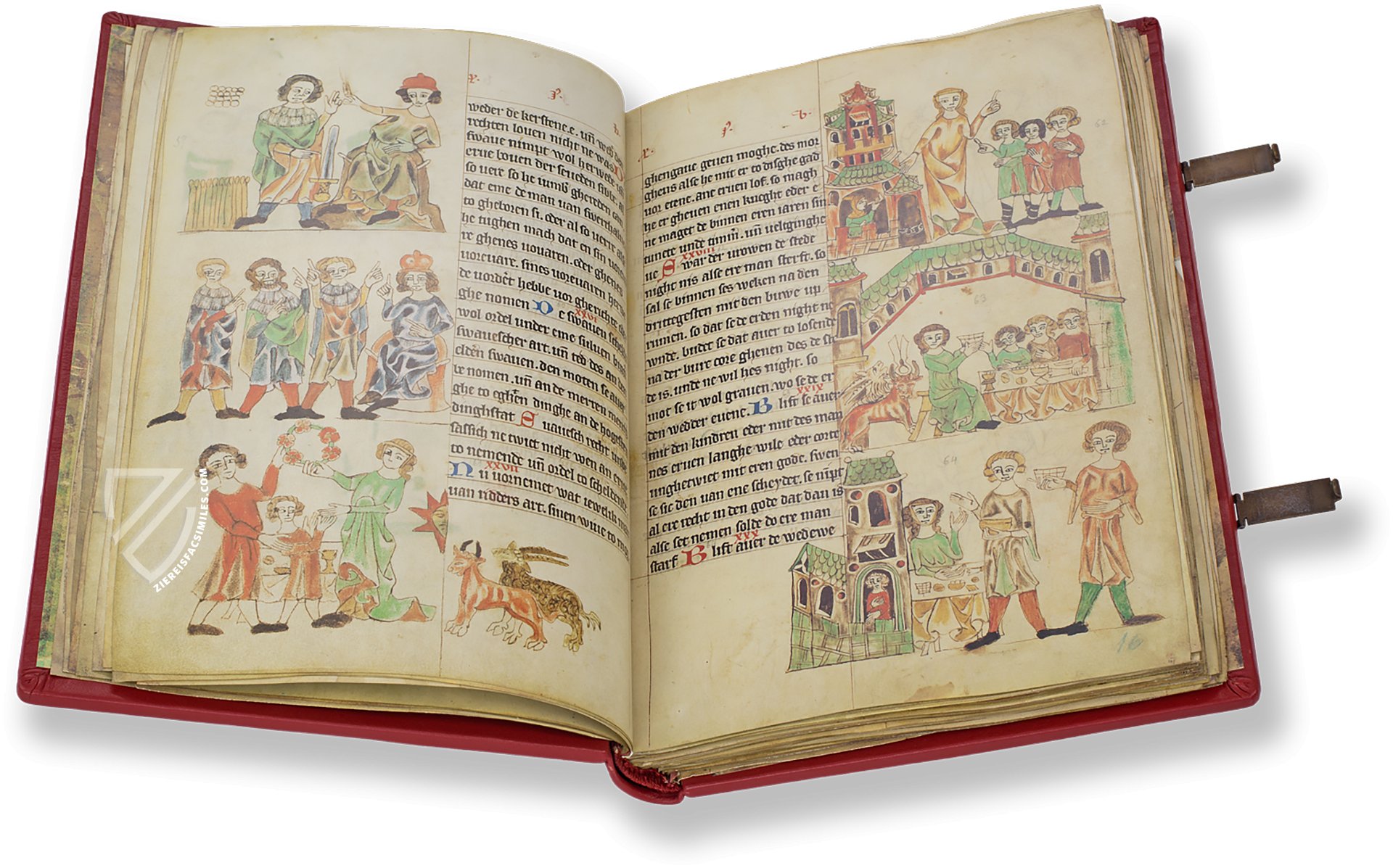

These elaborate foliate borders were also often populated by animals, humans and hybrid creatures, who usually do their humorous mischief in the margins - much to the amusement of the users. Mostly associated with courtly life, these scenes sometimes take place in medallions enclosed in the vines or even formed by the tendrils themselves.

Trompe l'œil: The Deception of the Eye

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

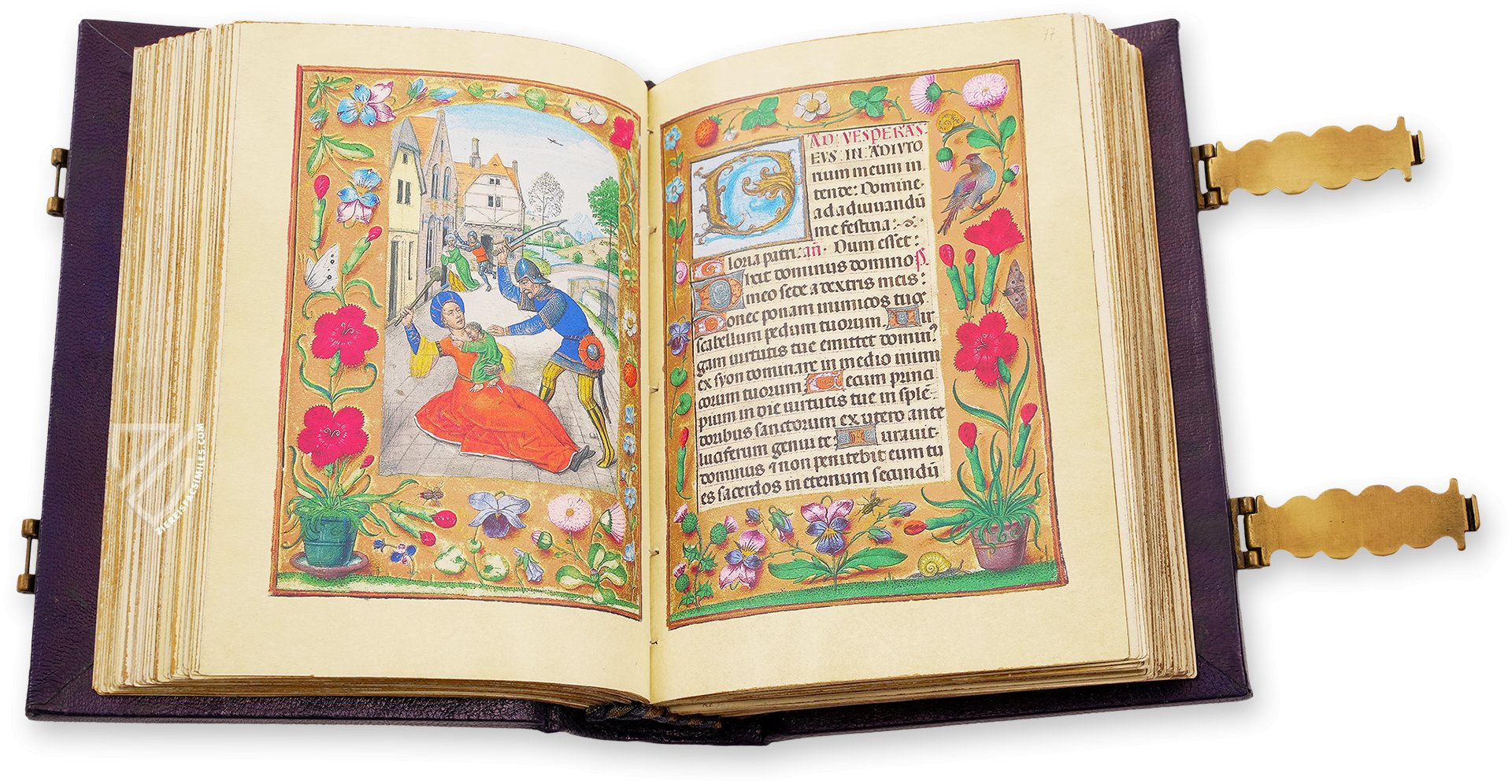

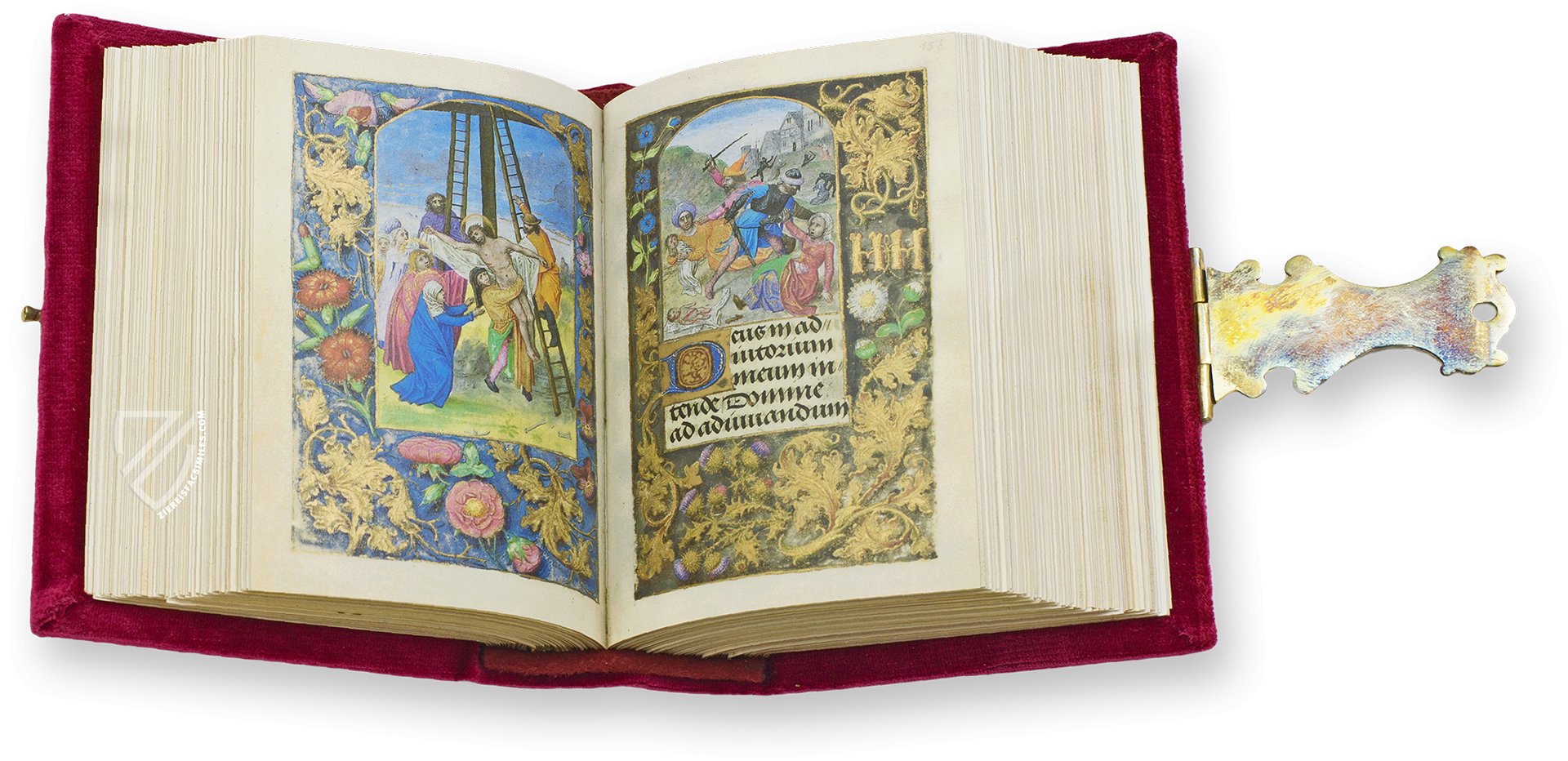

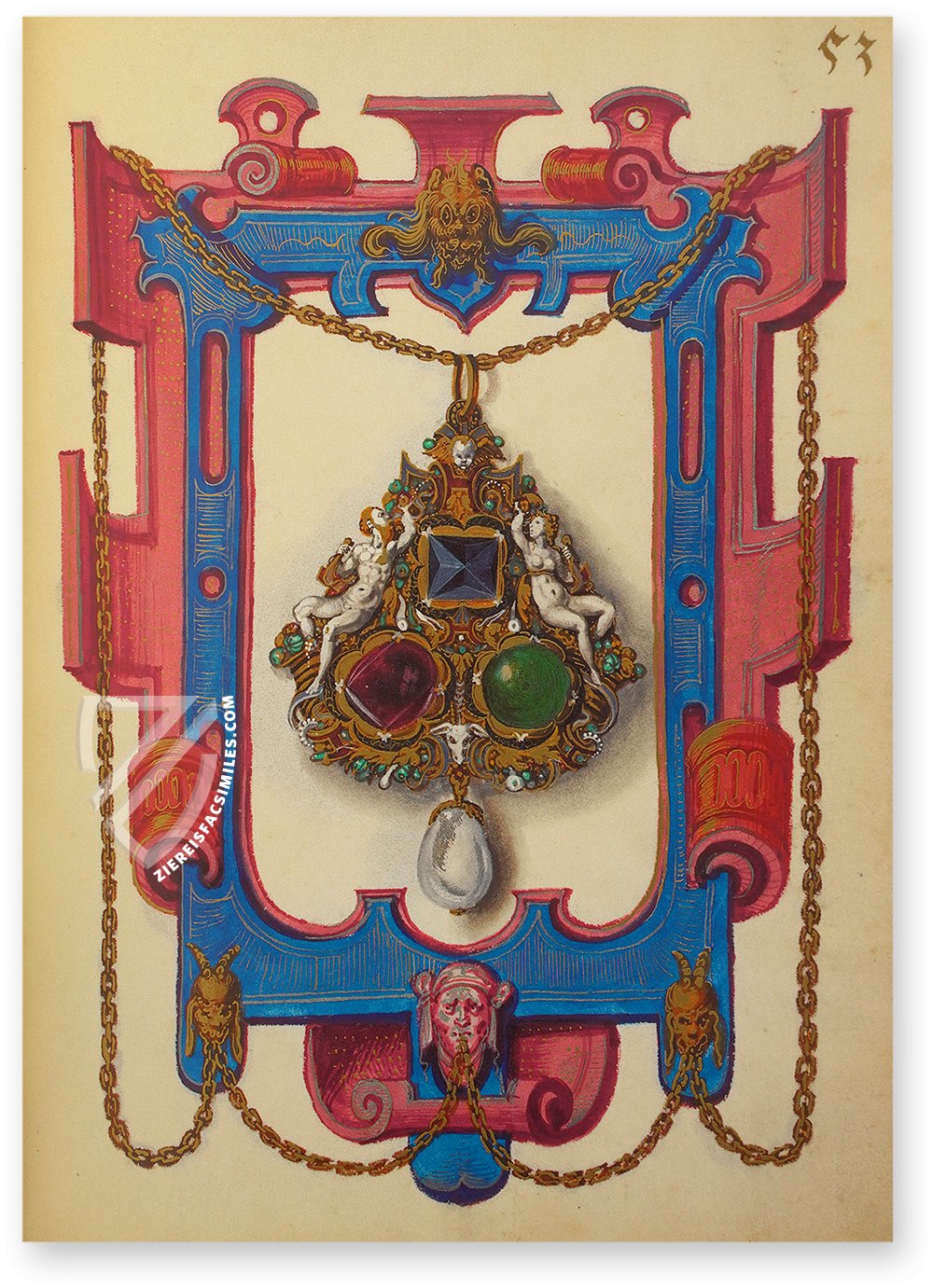

Over time, Gothic book illumination refined these forms and increasingly enjoyed decorating the borders with deceptively realistic-looking vegetal vine scrolls, flowers, fruit and small animals. With their naturalistic appearance and natural-looking shadows, the borders resemble collages of artfully arranged physical objects lying on the pages - an effect called trompe l'œil.

In trompe l'œil borders, all kinds of objects could be imitated and put together like collages

This effect could also be created with other materials such as stone or metal. Precious metalworks with gemstones were often imitated, such as in the Berlin Hours of Mary of Burgundy. In the Book of Hours of Alexander VI. Pope Borgia, however, a stone grid is adorned with flowers and banderoles.

The Book of Hours of Philip II takes this phenomenon to its peak, demonstrating the artistry of the Renaissance. The borders of this masterpiece of book illumination imitate almost the entire spectrum of materiality: from delicate flowers, dainty birds and juicy fruit to marble, cameos and gemstones. In between, human figures and grotesques can be found throughout.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Infinite Historiated Borders: Vast Landscapes in Narrow Margins

To the facsimile

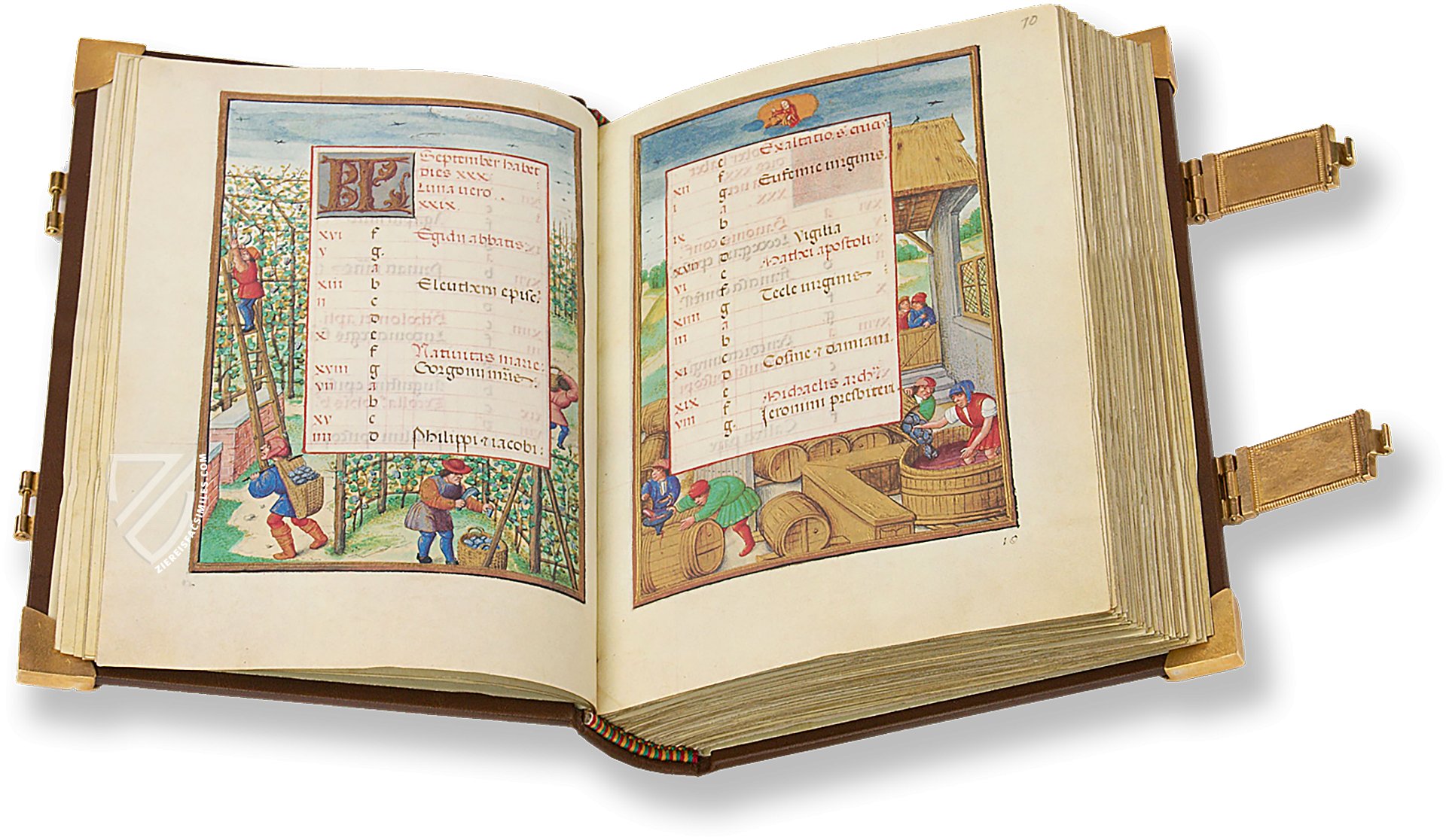

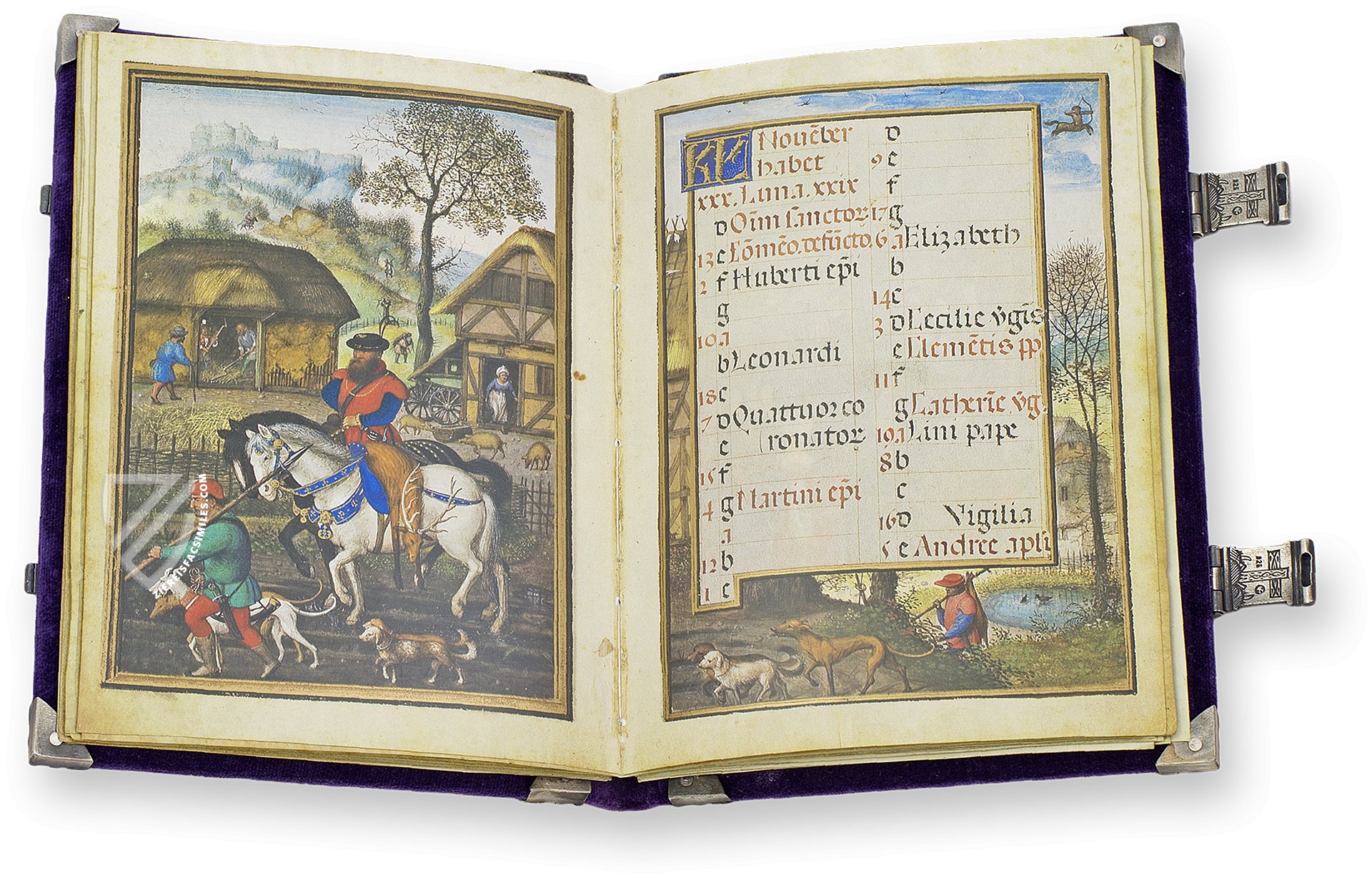

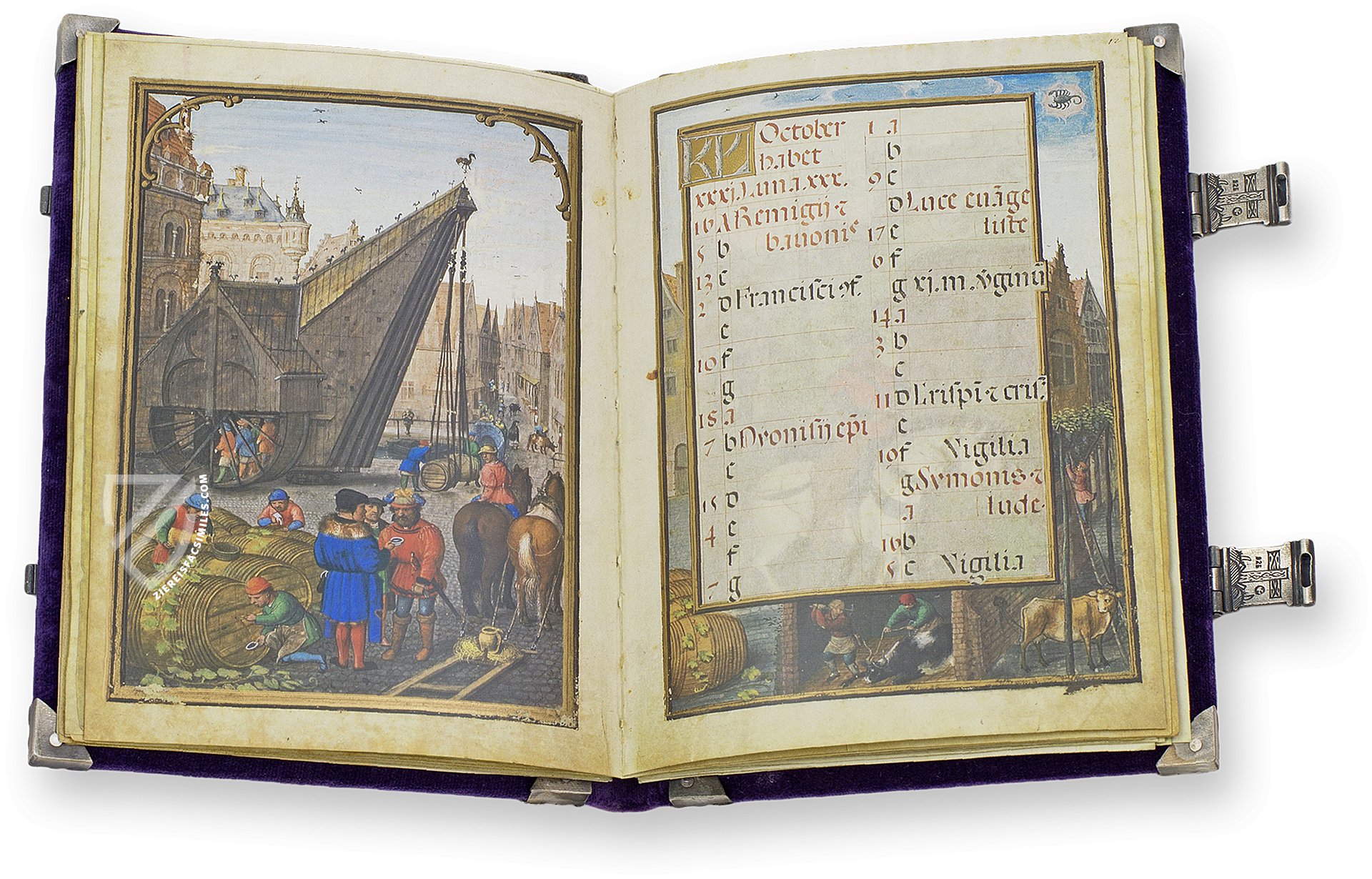

Borders could also house entire (urban) landscapes, which usually had a connection to the miniature or text they surrounded. In the books of hours and prayer books of the Gothic and Renaissance, it became extremely popular to transform the images of the labours of the month in the calendars into historiated borders. The Book of Drolleries - The Croy Hours, for example, illustrates the grape harvest and wine pressing in expansive landscapes on the two pages for the month of September.

Sometimes the book artists merged the central scenes with the surrounding borders, which created a very unique aesthetic and made the created pictorial spaces appear particularly vast. It also allowed the use of the entire page format, as the Rohan Hours and the Book of Hours of Philip II stunningly exemplify.

Framings do not always differentiate an inside from an outside

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Hammer, Chisel and Angle: Framing Fantasy Architectures

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

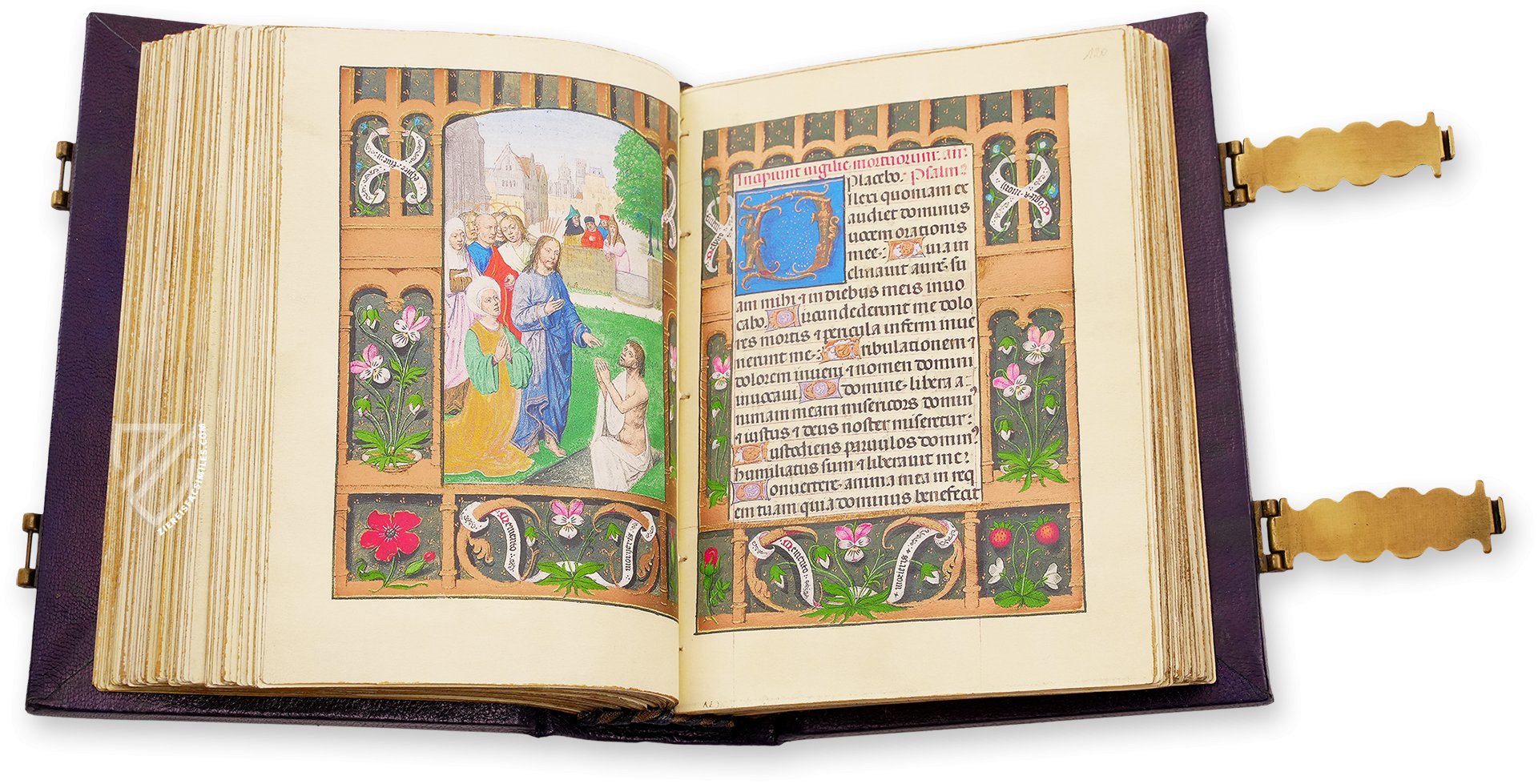

There were no limits to the design of the marginal pictorial spaces. Architectural framings have a long tradition in medieval book art, hence it is no surprise that Gothic borders were often decorated with detailed architectural elements. Particularly fascinating are examples of pictures in which the miniature and the border spatially interact. For instance, the border of the Book of Hours of Alexander VI. Pope Borgia shows a liturgical room with an altar set up for mass. Above it, the central miniature with the crucifixion scene can be observed as if through a window into the past. At the same time, the key event of Christianity is transferred to the present of the praying person, which is represented in the border.

To the facsimile

The Picture as a Window: Painted Window Frames

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

In Renaissance book illumination, these architectural borders were eventually developed into imitations of real window frames, which convey a strong impression of spatial depth through shadows and perspective views. This corresponds to the early modern idea of the picture as a window into the depicted space. These could be wide landscapes, further architecture or specific interiors, as Les Triomphes de Petrarque and the Jewel Book of Duchess Anna of Bavaria beautifully demonstrate.

Elegant Columns and Filigree Canopies: Subtle Image Edgings

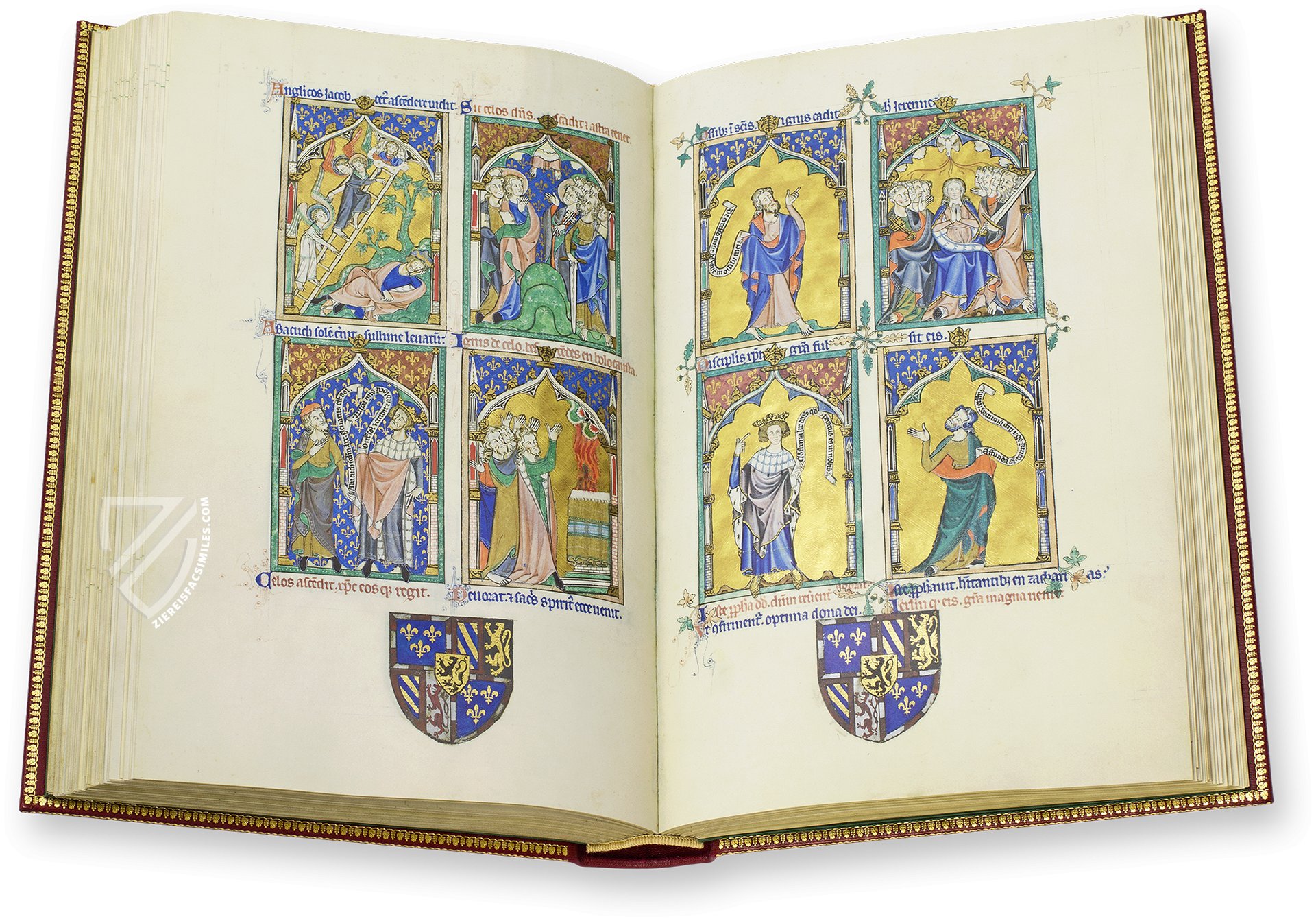

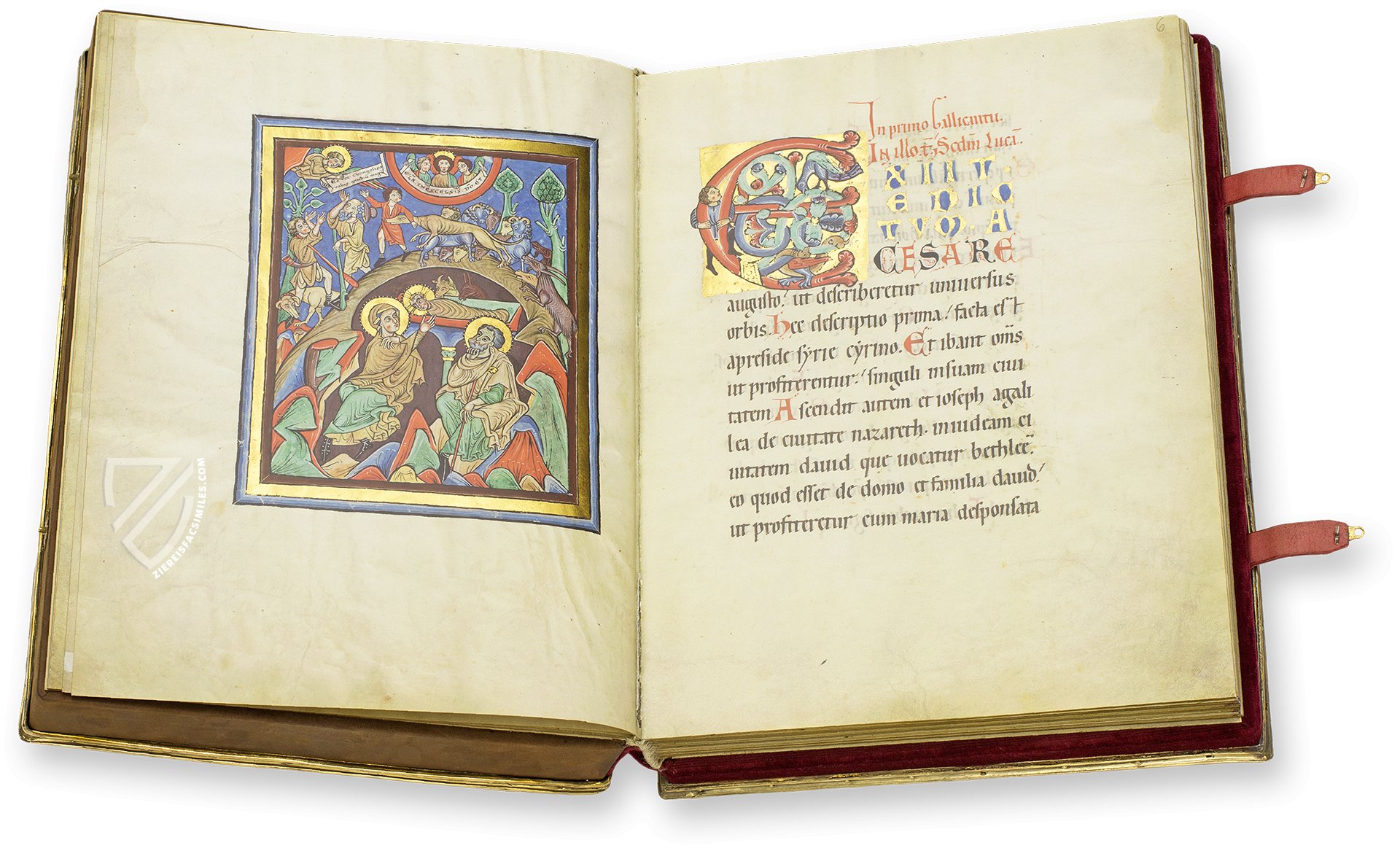

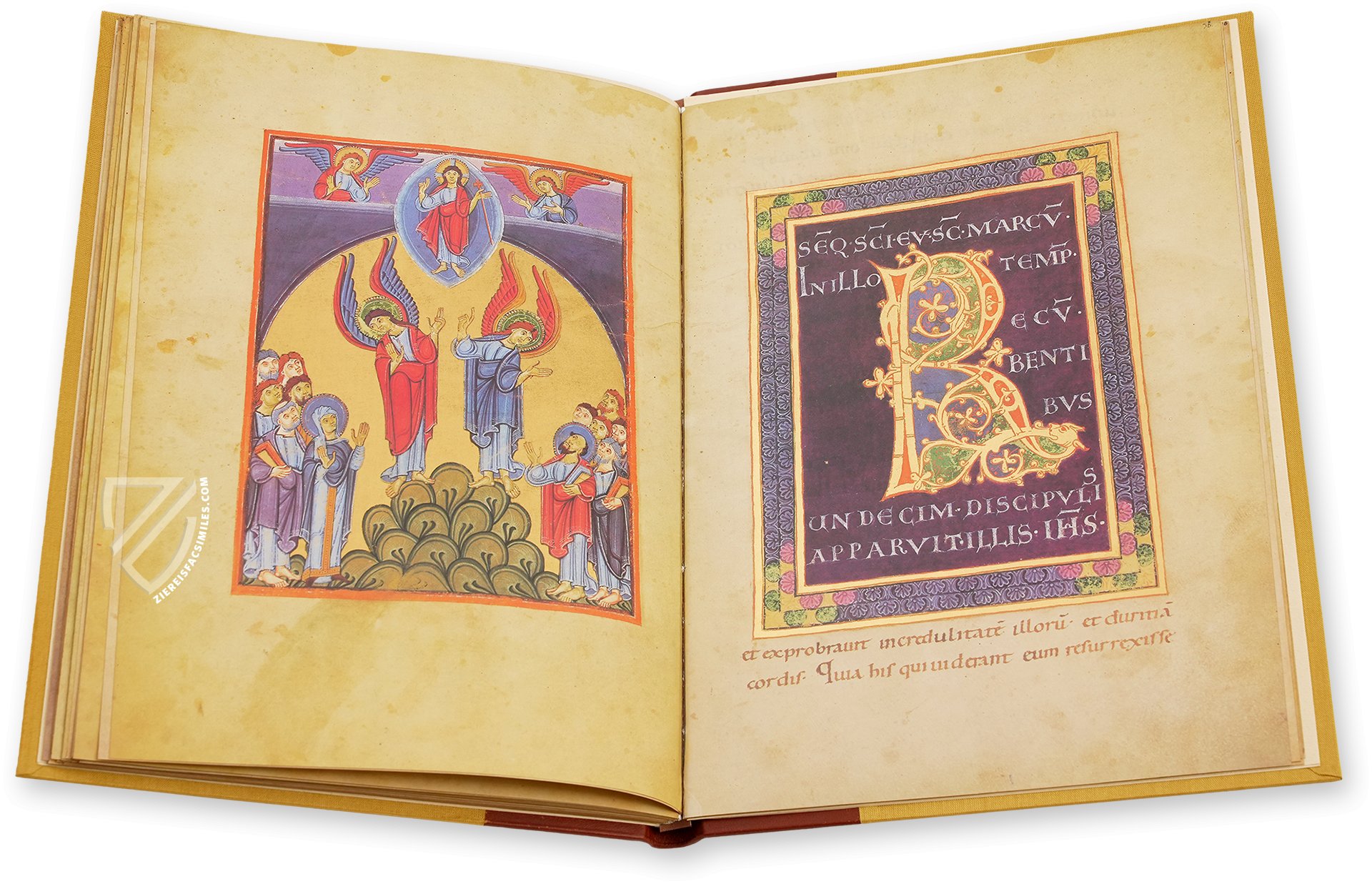

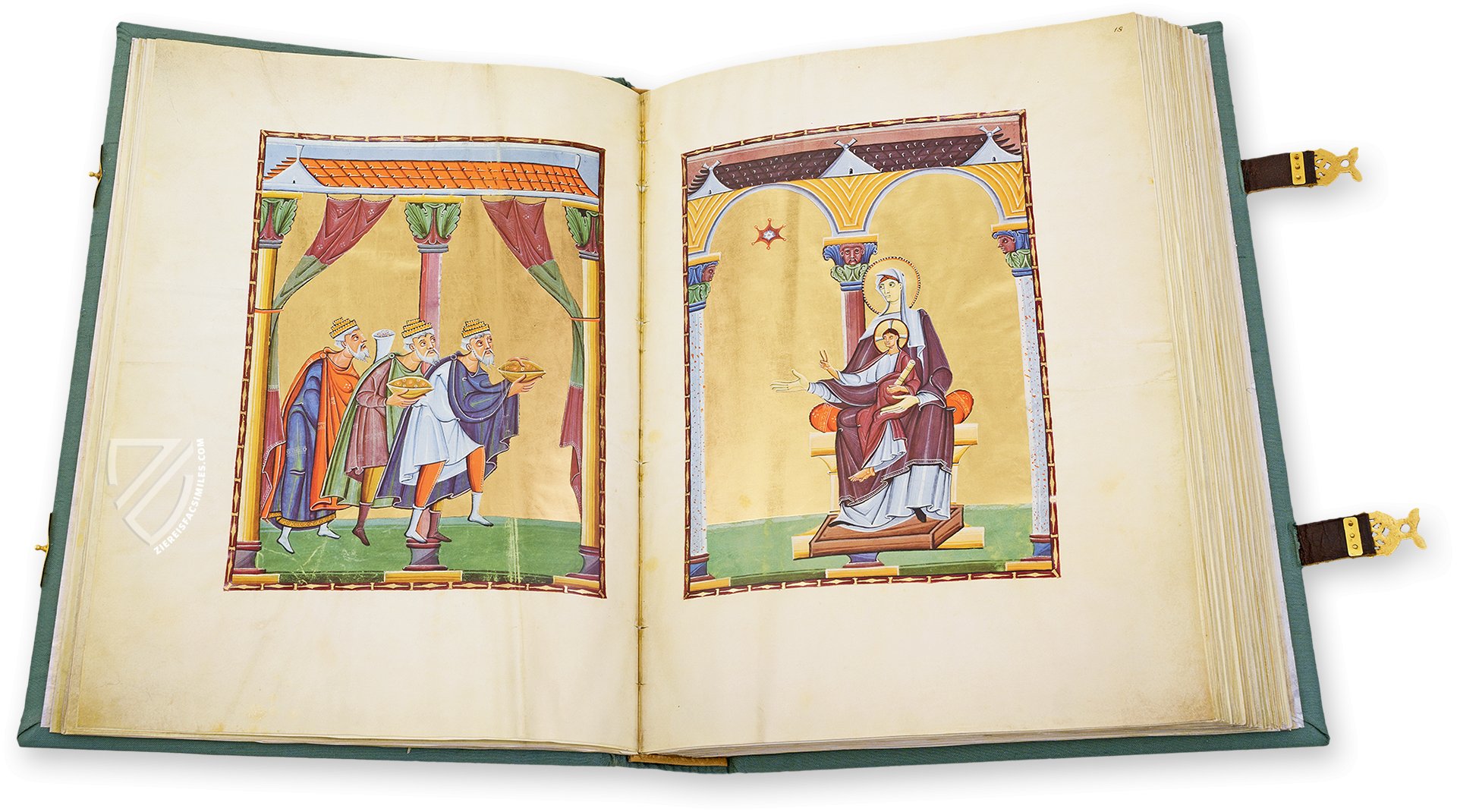

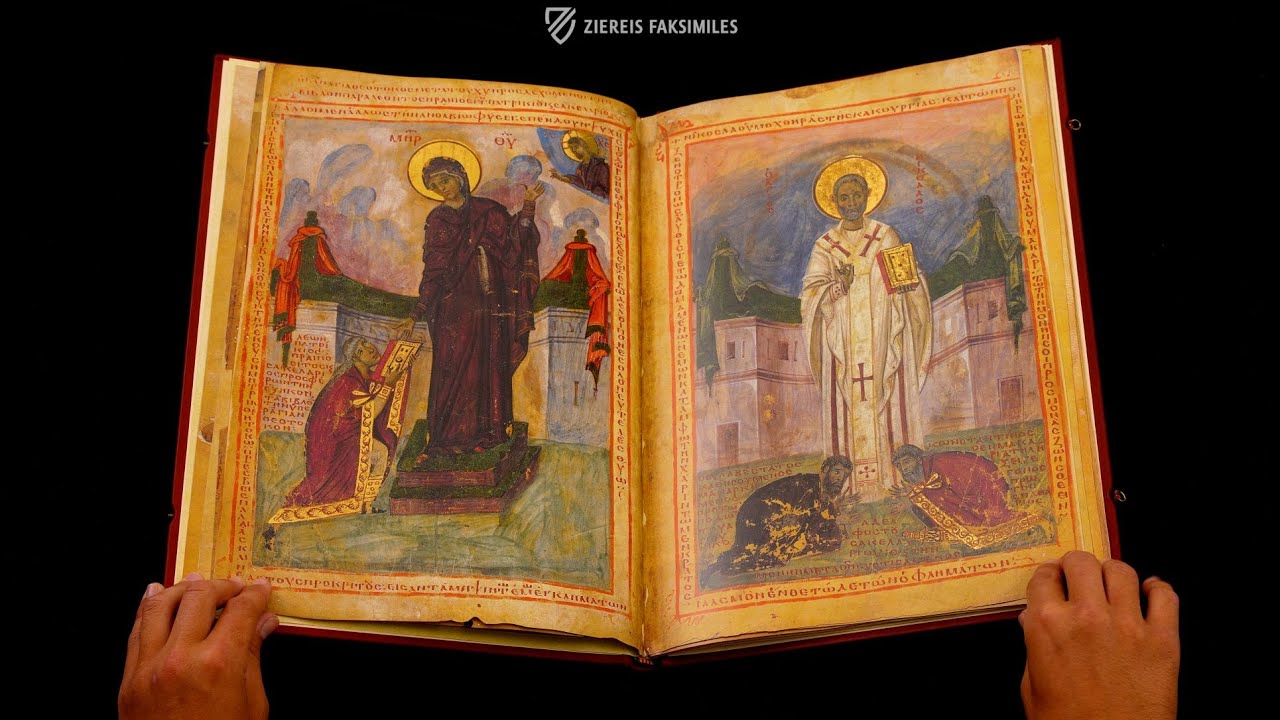

Throughout the Middle Ages, miniatures were also repeatedly framed in more subtle forms of architectural framings. In most cases, the association with architectural arches is merely evoked by flanking the picture panel with two columns connected by arches, canopies or roof constructions. Sometimes these frames are so restrained that they only become apparent at second glance - such as in the Ingeborg Psalter.

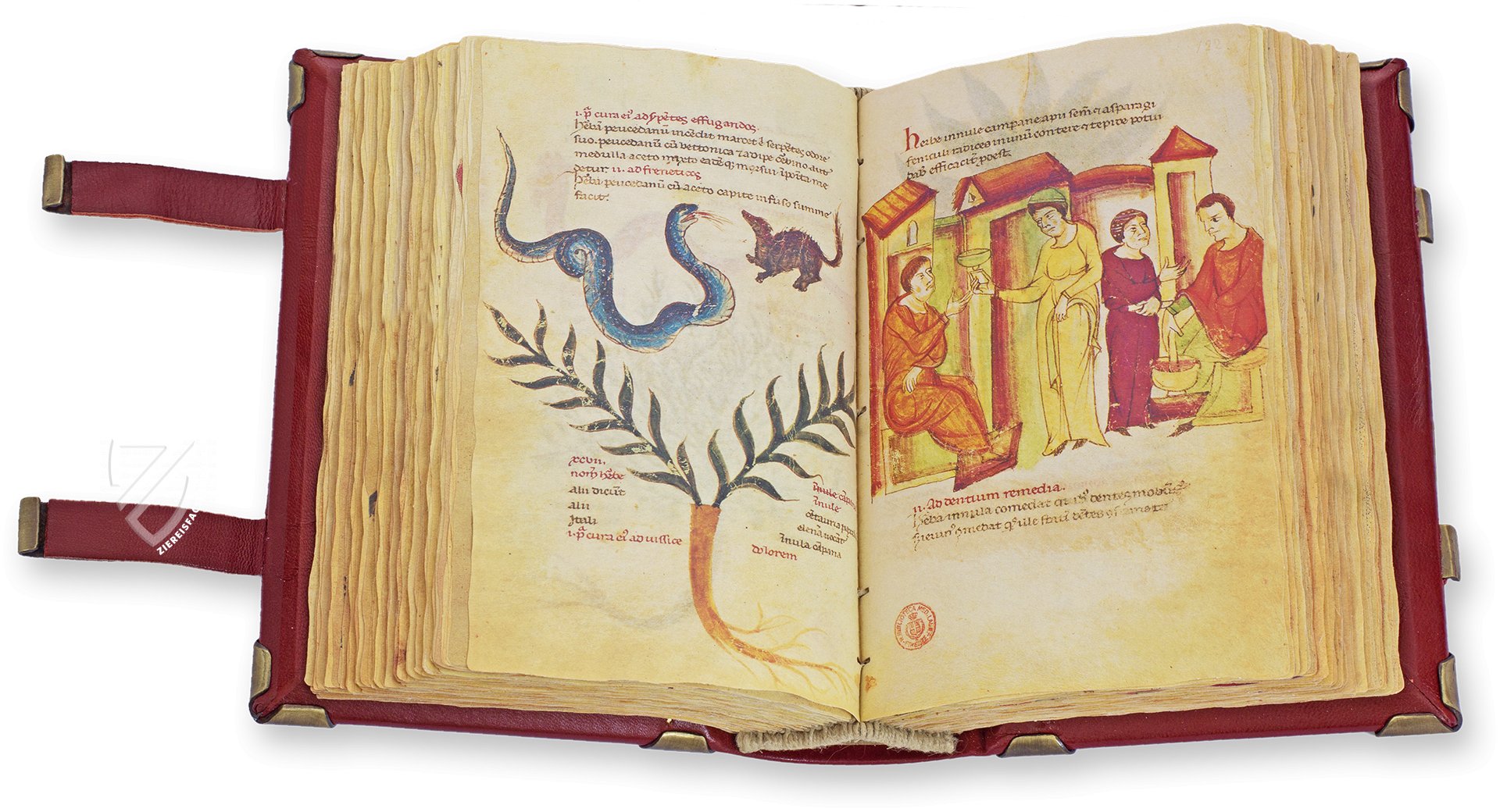

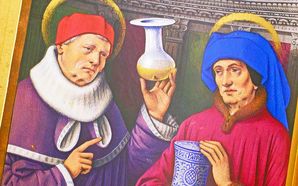

This design vocabulary is based on the ancient tradition of depicting majesties and authors under canopies and arched architectures. It was already adopted in the early Middle Ages for all kinds of portraits of authorities and remained firmly anchored in the Western iconographic canon for a long time. Probably the most striking manifestation of this tradition is the image type of the evangelist portrait, in which an evangelist accompanied by his symbolic animal appears as an author under an arc.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Captivating Spatial Constructs: Building Pictorial Spaces on Parchment

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

However, framings of architectural shapes could also be multi-layered and dominating, as the Salzburg Pericopes artfully visualize. Walls, towers, houses, arches and doorways often create complex pictorial spaces in which several levels of action and time are connected. The framing architectures define the structure of the images and play a decisive role in determining its aesthetics.

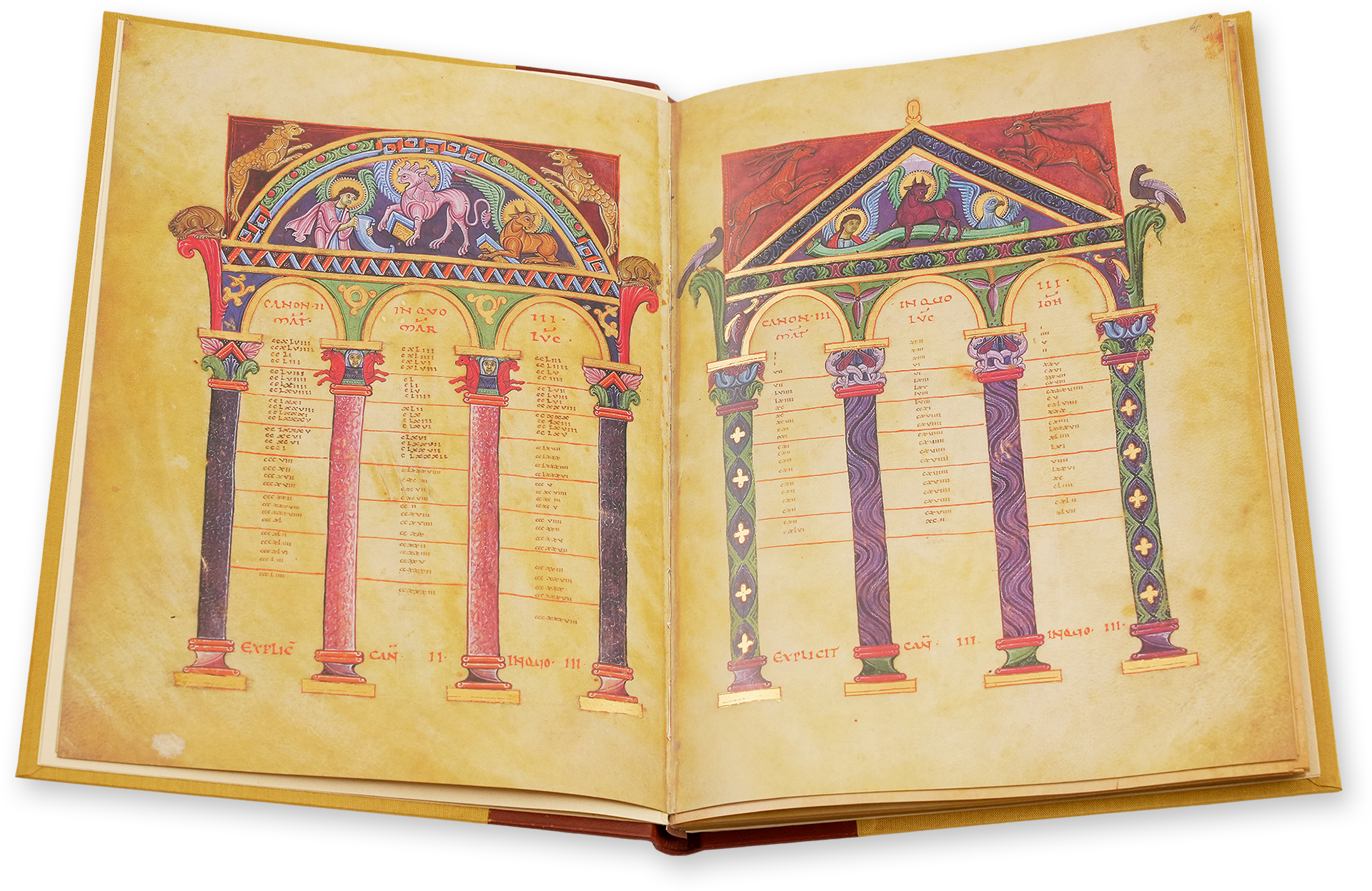

Time-honored Tradition: Artful Arcades for the Gospel Canon

Another late antique tradition is the framing of the canon tables with columned arcades, in the design of which medieval illuminators gave free rein to their creativity and imagination. While the tympana are usually decorated with Gospel-related imagery, the remaining architectural elements display a breathtaking variety of colors, ornaments and capitals. Animals and plants are also often part of these diverse framings.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Endless Possibilities: Frameless Book Illumination

The counterpart to the many framed miniatures are those illuminations without framings. They are just as common throughout the Middle Ages and create a stronger visual connection between text and image.

Frames, on the other hand, tend to separate the image from the text and create clear, independent pictorial spaces. The mode of presentation chosen was never random, but followed the overall concept of the book. Framings could take on diverse and important functions within these. They can therefore be seen not only as mere decoration, but also as mediums of image and meaning as well as a creative structural element of book illumination.